There is no gainsaying the necessity of rapid capital accumulation in a country like India, which wants to sustain the present high-growth phase, and has ambitions of a “developed-country” per capita income of $12,000-15,000 in nearly three decades from now.

Capital, as it is heaped up, enables creation of new fixed assets and working capital, and greatly aids assimilation of technologies for higher production efficiency. But undue concentration of capital is highly deleterious, as it raises the incremental capital output ratio.

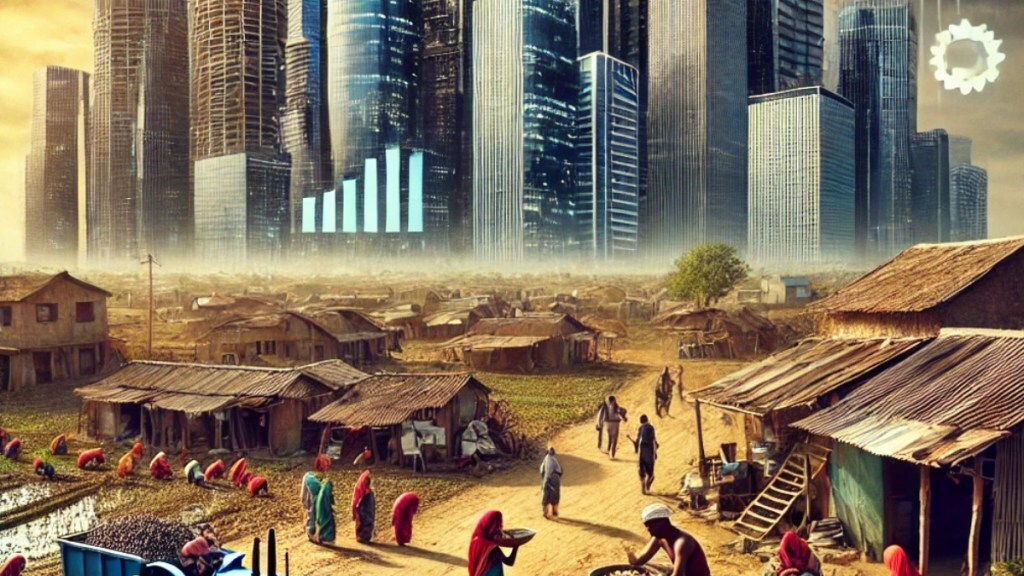

The monumental jump in the share of large corporate groups in the gross domestic product (GDP) has caused capital/income deprivation for the rest of the economy, even when the external world is volatile. It’s staggering: corporate profits quadrupled between FY20 and FY23 to hit a 15-year high in FY24, even as the nominal GDP grew just 47% between FY20 and FY24.

While this was highlighted in the Economic Survey 2023-24, Motilal Oswal estimates that profit-to-GDP ratio for Nifty 500 companies was at 4.8 in 2023-24, and for the entire listed universe, at 5.2. Super-normal profits for large companies came at the expense of almost all other economic sectors, including its own workforce.

Employment growth in Corporate India has stagnated in recent years, even while salaries have fallen in real terms. A recent report by FICCI-Quess Corp reportedly revealed that the compound annual wage growth rate across six selected sectors was in the range of 0.8-5.4% between 2019 and 2023. Given that annual average inflation in the period was 5.7%, the real growth in corporate salaries was negative. A Bank of Baroda report, based on a sample of 1,196 companies, showed that their employment growth declined sharply to 1.5% in FY24 from 5.7% in FY23.

There is also a growing “informalisation” of the workforce, meaning shift from regular to contract jobs. An acute income crisis is being faced by large sections of India’s population, households and micro, small and medium enterprises being the worst hit. Rural India has been seeing a decline in real wages for quite a while.

Curiously, this was a period that saw sharp and sustained economic growth and rapid improvement in all economic health indicators, including earnings of large companies, and the tax-GDP ratio. A rise in rural wages/income was, however, visible in the period between 2010 and 2016, even though economic growth was relatively subdued; this phase was quickly followed by a generally declining trend, accentuated after the pandemic. What this shows is that income growth was more widespread during the phases of fiscal expansion (consumption booster).

In other words, capital accumulation, unless complemented by policies that have sufficient redistributive elements, won’t produce a sustainable growth paradigm.

The policymakers must be cognisant of the fact that even when national output is strong, the dominant economic actors could very well dig their heels in, by keeping worker pays low, and over-regulating new recruitments. The corrective policies must engineer a shift in the terms of trade, and more even distribution of the national income.

The economy needs to generate an average of nearly 7.85 million jobs annually until 2030 in the non-farm sector to cater to its rising workforce. There are also possible risks of generative artificial intelligence (AI) to job-producing sectors like business process outsourcing, even as the next decade will see major productivity gains from the AI diffusion.

It is imperative at this juncture to enhance labour efficiency, for which wages are as crucial a determinant as improved skill levels and technology upgrade.