Tell us about the journey of writing Mountain Mammals of the World.

I have a habit of writing a daily diary on my field visits, and I still keep those diaries safely. I wrote my first diary when I visited Ladakh—which was my first exposure to mountain mammals really—in 1958, when I was in college. Since I already had that collection, and had written three books prior to this as well (Beyond the Tiger: Portraits of Asian Wildlife, The Indian Blackbuck, and A Life with Wildlife: From Princely India to the Present), things came together easily.

I had been wanting to write about mountain mammals for quite long, but never could get to it because there were always a thousand other things to do. Then came Covid and I could not travel, so staying at home pushed me to start this book. And then, of course, since I had started it, I had to complete it. Covid was actually responsible for this book, otherwise I would not have written it.

From drafting the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, to chairing the Wildlife Trust of India and working with WWF’s Tiger Conservation Programme and the National Forest Commission, you have practically shaped India’s wildlife conservation efforts. What does the future of our country’s fauna look like, especially in the face of climate change?

The wild fauna will be dependent on their habitat. Otherwise, you can only have captive fauna in cages—big and small. So, you start with saving the forests, and in the process, you save the wildlife, the biota, the habitat, and the diverse ecosystems, which I regard are the natural national heritage of the country. So, to save the animals is the means to an end for me, magnificent though they are individually.

But in a democracy like ours, they will only be saved if the people want them to be saved—and they have to want them to be protected not in captivity but in their natural habitat. The government, in this regard, can either lead or can meekly follow what the people want to get votes. Unfortunately, the environment does not get people’s votes in this country, which is a tragedy.

In times when globally biodiversity is under threat constantly, how do we go about protecting the wildlife?

If you read the Wildlife (Protection) Act, we have a category called community reserves, wherein communities themselves protect wildlife and nature in their respective areas. That should be encouraged. The people’s job would be to protect the wildlife, and the government’s job would then be to support them—financially and otherwise. Communities like the Bishnois in Rajasthan have been doing this for years. More people should be given the opportunity and encouragement to protect their own wildlife, because while each individual effort matters, a community-driven push can do wonders. In the process, you are saving mountains, the ecology, water resources, and more. Also, it’s important that people start looking at wildlife preservation and conservation from the perspective of human survival too.

Since there’s still contention around the taxonomic classification of mountain mammals, does their conservation become more difficult?

Yes, and no. Previously, the taxonomic classification was based on outward appearances, colouration, etc, which was called morphology. Now it is more systemic and includes a DNA analysis. I believe that DNA analysis should be the arbitrator when it comes to deciding on taxonomic classification, because many species haven’t had DNA testing done yet. When this happens, there could be more sub-species being discovered and conservation efforts being started.

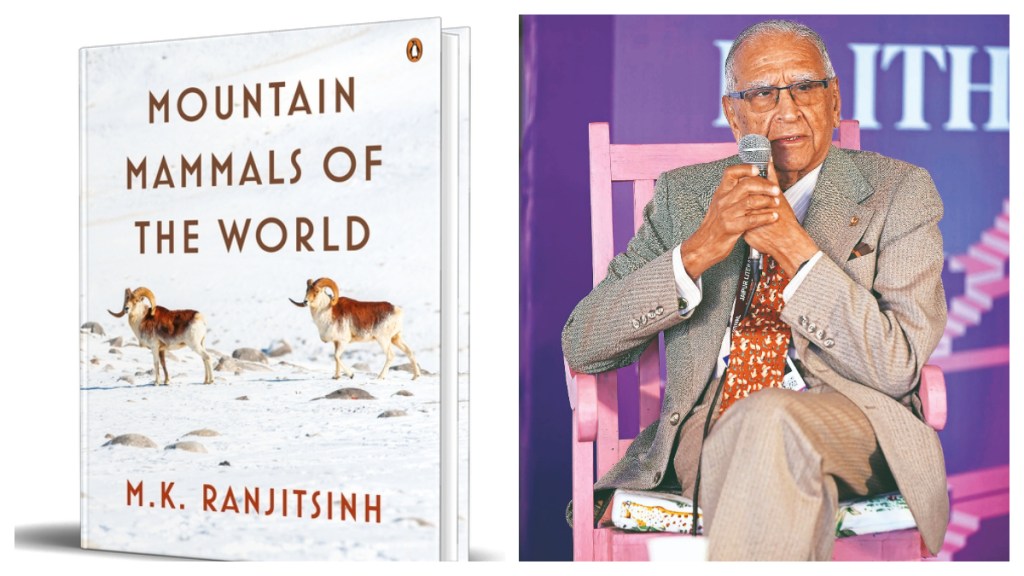

Mountain Mammals of the World

MK Ranjitsinh

Penguin Random House

Pp 400, Rs 2,599