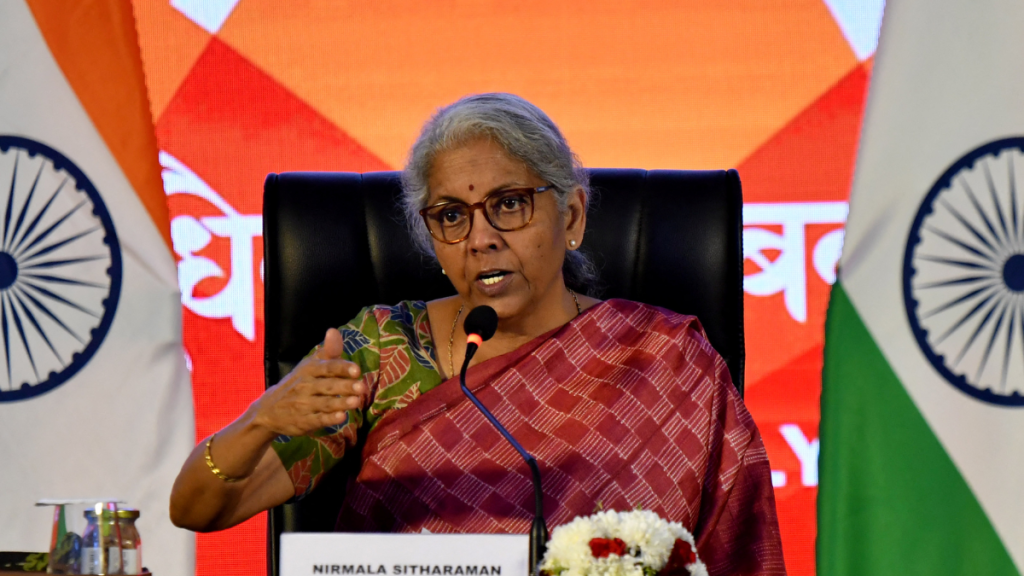

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s recent statement that the Narendra Modi government in its expected third term will undertake major reforms at the third level of the federal structure of government has brought the local bodies (LBs) and their below-potential existence, into focus again.

Even three decades after the Constitution mandated the setting up of empowered local self-governments at the level of Panchayats and municipalities, these institutions have not been able to acquire the financial and policy-making powers envisaged at the time of the constitutional amendment. As a result, key objectives of governance aren’t being met at the desired pace, even in cases where budget outlays have risen meaningfully. The objectives that are work in progress include ease of investments and doing business, achieving optimal outcome of the government’s welfare budget, making programmes flexible to the needs of the society and addressing disparity across regions in accomplishment of sustainable development goals.

Experts have long blamed the states, which were empowered to give effect to the Constitutional provisions, for their lack of interest in conducting regular elections of the local self-governments, devolving adequate powers to them, and boosting their financial resources. Of late, there have also been concerns that Central government programes are designed with lesser involvement of states in decision-making, and that the conditions imposed in regard to transfer of assorted central funds to states/LBs are restrictive, and without due regard to specific local needs.

The Centre’s focus should be on reforms to address local bodies’ capacity constraints, augment their own revenues and nudge states to empower these bodies to strengthen governance at the grassroots level to ensure effective service delivery to citizens, experts said.

“The most critical reform required is to devolve the functions, functionaries and funds to the ULBs according to the provisions and spirit of the 74th Constitutional Amendment (Part IX-A) of the Constitution,” said Kaustuv Kanti Bandyopadhyay, Director at the Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA).

The 73rd (rural bodies) and the 74th (urban bodies) Constitutional Amendment Acts, 1992 direct the states to establish a three-tier system of Panchayats at the village, intermediate and district levels and municipalities in the urban areas respectively.

States were expected to devolve adequate powers, responsibilities and finances upon these bodies to enable them to prepare plans and implement schemes for economic development and social justice. These Acts provide a basic framework for decentralisation of powers and authorities to around 2.7 lakh Panchayati Raj/Municipal bodies at different levels. However, while some states like Kerala and West Bengal have robust LBs (see chart), many states are yet to pay adequate attention to this key reform in governance mechanism.

As against the Constitutional provision for devolution of all key taxes to urban bodies, only one state has done so while none of the states have devolved of all functions as per the 12th Schedule of the Constitution in practice. Only ten states have constituted state finance commissions, that too largely for namesake purpose as the 15th Finance Commission has linked it to the release of grants. “Complete devolution of urban planning function with commensurate human and financial capacity is fundamental. The devolution of taxation is critical to local resource mobilisation,” Bandyopadhyay said.

Only 42% of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act, which provides for the devolvement of powers to urban bodies, has been implemented by states, according to Janaagraha, a not-for-profit body working for the betterment of life in India’s cities and towns. Urban planning is a municipal function that is mandated to be devolved to city governments by the Constitution. Janaagraha analysis across 35 states/UTs finds that Kerala is the only state to specifically recognise the role of city governments in the planning process in its planning legislation.

Each year, urban and rural local bodies lose a significant portion of central grants for not adhering to three basic norms: regular elections, audit of accounts and steps to augment their own revenues.

Even as the 16th Finance Commission (FC) will start work to suggest grants to promote national goals during FY27-FY31, FE analysis of the first four of the 15th FC’s six-year award showed that states have lost around Rs 65,000 crore of the Central government grants for not meeting conditionalities for the incentives.

Imagine what these institutions could have done to improve basic services to citizens in terms of providing healthcare, education, sanitation and other services that would have improved their living conditions. The 15th Finance Commission grant awarded Rs 4.36 trillion to support local governments for a five-year ending FY26.

“Finance Commissions have been earmarking funds for local bodies through state governments. The state governments have no incentive to do anything,” said Sudipto Mundle, Chairman of the Centre for Development Studies. “So, the Centre may have to ensure that the states get some reward for the timely transfer of money to Panchayats and municipals. Unless the states have their skin in the game, they will not bother,” Mundle said.

Besides the lack of capacity at Panchayat and municipal levels, Mundle said states have no interest in empowering elected local bodies as they would take away powers from MLAs. “Because of the vacuum, they call the shots now. The day elected panchayats and municipalities are empowered, the MLAs will suffer. That’s why states have no incentive to do anything,” Mundle said.

To build capacity at the local level, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) in collaboration with state governments is now extending audit support to all the local bodies to help them improve governance and help utilise central grants fully to provide services.

Currently, CAG does a full audit of local bodies in West Bengal, Kerala and Karnataka while providing support for such audits in other states. Going forward, the CAG plans to put out annual performance and compliance audits of local bodies for each state similar to the exercise at the state and national levels to increase transparency and data availability to give a true picture of general government finances.

Article 243-H of the Constitution empowers Panchayats to impose, collect, and allocate taxes, duties, tolls, and fees. The decisions regarding taxes to be decentralised to local governments are, however, mainly at the discretion of state legislatures. In addition to these revenue sources, Panchayats also receive funds for executing Centrally Sponsored Schemess like the Rashtriya Gram Swaraj Abhiyan, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme, the Mid-day meal scheme, the National Horticulture Mission, etc.

“In my view, the third tier is still at a conceptual level. A lot of money is going to these bodies, but nothing much is happening at the ground level due to poor management except in a few schemes like MGNREGS,” said N R Bhanumurthy, Vice-Chancellor of Bengaluru’s BASE University. “It’s important to handhold local bodies to solve their capacity constraints,” Bhanumurthy added.

Janaagraha has suggested creation of a high-powered council between union and state governments, along the lines of the GST Council, to evolve consensus on overhaul of the 74th Constitutional Amendment to empower local bodies more effectively.

With the finances of Panchayati Raj Institutions facing constraints due to their limited own revenues, a Reserve Bank of India report in January this year said the PRIs need to intensify their efforts to augment their own tax and non-tax revenue resources and improve their governance. The report noted that around 95% of their revenues are in the form of grants from the Centre and states, restricting their spending ability that is already hampered by delays in the constitution of State Finance Commissions (SFCs).

Drawing upon data on 2,58,000 Panchayats, the RBI report found that the average revenue per Panchayat from all sources – taxes, non-taxes and grants – was Rs 21.2 lakh in 2020-21, Rs 23.2 lakh in 2021- 22 and Rs 21.23 lakh in 2022-23. The decline in 2022-23 was owing to lesser devolution of grants.

The own revenues of the Panchayats – generated by imposing local taxes, fees, and charges on various activities, including land revenue, professional and trade taxes, and miscellaneous fees – were only 1.1% of their total revenue during the study period. Non-tax revenue – primarily from Panchayati Raj programmes and interest earnings – is also modest, with a share of only 3.3% of their total revenue receipts. Panchayats in Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Telangana reported higher non-tax revenue than other states.

Municipal revenues/expenditures in India have stagnated at around 1% of GDP for over a decade. In contrast, municipal revenues/expenditures account for 7.4% of GDP in Brazil and 6% of GDP in South Africa.

In order to improve the buoyancy of municipal revenue, the Centre and the States may share one-sixth of their GST revenue with the third tier, 13th Finance Commission chairman Vijay Kelkar had said.