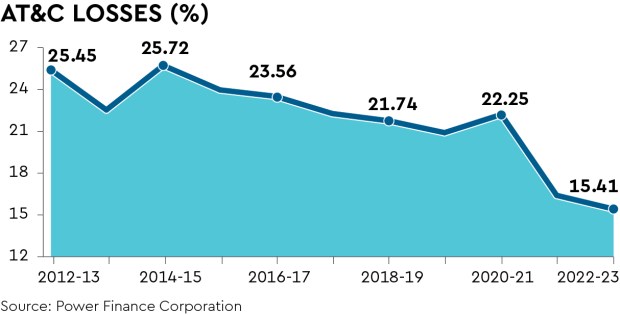

There has been a lot of chest thumping over the fact that the aggregate technical and commercial (AT&C) losses in the Indian power distribution sector, which was close to 25% in 2015, now stands close to 15%. A 15% AT&C loss would mean that one has not been able to account for 15% of the power that was received in the periphery of a distribution company (discom) and, hence, this is a leakage in the system. And the discom is losing revenue to that extent. In one were to put it in simplistic terms, had the discom been able to plug this leakage, it could have offered lower retail tariffs. Thus, in a system where retails tariffs are determined on a cost-plus basis (as in our case), it is the consumer who loses because of the inefficiency of the discom.

Before examining whether this euphoria over the AT&C loss of 15% is justified or not, it would be useful to see what the government has done over the years to lower AT&C loss figures. The story began sometime in 2001, when the Accelerated Power Development Scheme (APDP) was introduced. Under this scheme, the Union government provided soft loans/grants to the states to improve their distribution infrastructure, including metering. The assistance was, however, linked to the condition there would be a reduction in the AT&C losses. Not all components of the APDP scheme were supposed to help in lowering AT&C losses. Some of the components were for system strengthening that would enable discoms to supply better quality power and, of course, a part of it was for metering, replacement of cables, etc, which would directly help in lowering losses. There have been several versions of the APDP scheme over the years, but what was common in all these was that they were linked to reduction in loss levels of the discom. The fact is that despite the thousands of crores of rupees pumped into the distribution sector, actual reduction in losses was marginal as can be seen in the graph.

The approach changed when the Ujjwal Discom Assurance yojana (UDAY) scheme was launched in 2015. For the first time, the Union government desisted from giving money to the states and, instead, provided sops like increased supply of domestic coal, rationalisation of coal linkage, allowing coal swaps from inefficient to efficient plants, etc. The scheme was operated through the issue of bonds, both by the states and the discoms. UDAY was never really a success and we went back to the old system of giving money to the states through the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS), initiated in 2021-22 for a period of five years. The total money involved was substantial, at about `3 trillion, which also included a budgetary support of a little less than `1 trillion. While the RDSS scheme will come to an end in about two years’ time, the government has announced the continuation of the scheme (as the second phase) for another period of five years (beginning from 2026-27) with financial implications that are identical to those of the first phase.

Now coming back to the figure of 15% for AT&C losses for 2022-23. There is little reason to be merry, given a clutch of considerations. First, the estimate of 15% is a provisional assessment, perhaps meaning that it is based on unaudited figures. Once the accounts are audited, a completely different picture may emerge. Second, given the fact that we had already reached 16.42% in 2021-22, the reduction achieved in 2022-23 is marginal as it is only an improvement of about 1%. So we are actually back to our old niggardly reductions of about 1% per year (or less) which we had witnessed over the period 2012-13 to 2020-21. As can be seen from the graph, we had achieved a substantial reduction in AT&C losses in 2021-22 when the loss level reduced by just under 6% over the previous year. However, what we must bear in mind is that 2020-21 was an abnormal year due to the pandemic. There were disruptions in revenue collection, consequent to which the loss figure actually went up by about 1.3% compared to the previous year (ie.2019-20). So what could have possibly happened was that the revenue that should have actually accrued in 2020-21 was made good in 2021-22, resulting in the massive fall in AT&C losses. Now that all the pending revenue has been accounted for in 2021-22, our AT&C loss reduction trajectory has also reduced to just meagre improvements.

Instead of doing some soul searching, the government was quick to publicise that we have achieved the loss level of near 15% as was planned when RDSS was launched. Nowhere did it mention that we were actually on 16.42% in 2021-22 and thus fared poorly in 2022-23. RDSS cannot be given the credit for reaching 15% AT&C losses since the detailed project reports have just been approved and money has been disbursed and now one is going through the process of tendering. So nothing much is available on the ground today. To give an example, while about 220 million meters have been sanctioned, only about 0.8 million have actually been installed. Benefits, if any, will probably be visible in 2024-25 or, better still, in 2025-26.

To sum up, reduction in AT&C losses remains as elusive as it was earlier. It only strengthens the thinking that it is more of a managerial issue rather than that of infrastructure. Of course, meters (especially pre-paid meters) do help, but they can only complement the managerial will to improve and cannot be a substitute. This author has always opined that given our political economy, doling out money to the states will not turn around the distribution sector. The answer lies in privatising the discoms with government handholding. The oft quoted example is that of Delhi.

Somit Dasgupta, senior visiting fellow, Icrier, and former member, CEA

Views are personal