By Dr. Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan and Dr. Sarika Rachuri

The summer of 2025 arrives with winds of change. April, a month that usually begins with jest and the lightness of All Fools’ Day, this year, is inundated with serious deliberations. In U.S., President Trump has announced sweeping tariffs. The world, taken aback, is now rethinking the very fabric of globalisation. Almost every country was affected by the onslaught of tariffs, which ranged from 10% to 104%.

China stands at the epicentre, facing the steepest hikes. In contrast, Chile, and the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region saw relatively benign tariffs, capped at around 10%. This inward-looking policy echoes economic doctrine of beggar-thy-neighbour—where a country seeks to improve its own welfare by shielding its industries behind high tariff walls, often at the expense of global partners who are themselves trying to protect their economies.

Only in the 1920s, these measures had a truly global impact. That decade saw the initiation of high tariffs in 1922 by Ford McCumber, culminating in the Smoot Hawley Act. This was followed by the Great Depression and World War II.

Now, for the first time since then, the world is witnessing protectionism of this magnitude, and those targeted by tariffs often respond with countermeasures, overlooking a critical principle: in trade economics, “it is not who you tax, but what you tax, that determines the real impact.” Before resorting to retaliation, nations must undertake a rigorous checklist – examining import-export composition, assessing price elasticity, and evaluating whether the tariffed goods are substitutable or essential.

Without this, retaliatory actions risk becoming symbolic gestures rather than strategic moves. In terms of geography, the export driven Asian countries bore the highest brunt of the tariffs, with China at the epicentre, but even military treaty allies being targeted with high tariffs. In contrast, the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region, and a few others, are at the lowest level of 10%. India, is somewhere in the middle at 26%.

From an economic perspective, the prudent way to cushion the blow of tariffs is to shift focus away from the identity of the retaliating partner and instead examine the underlying economics of trade of the basket of imports and exports. What needs to be studied, is the price elasticities of the import and export basket. If the combined absolute values of these elasticities of exports and imports exceed one—a threshold known as the Marshall-Lerner condition—then trade balances can adjust favourably, even in the face of tariff hikes. This approach allows countries to make data-driven decisions rather than simply provoke symbolic tension.

There can also be geo-strategic considerations in retaliation, and, while India is negotiating a bilateral trade agreement (BTA) with the U.S., slated to be completed by September 2025, it also needs to assess the impact of the country level imposition of tariffs, and this is laid below.

India Impact and Opportunities

India’s export basket to the U.S., the import intensity, competing exporters in the same basket, as well as the possibility of trade shift into or out of India, will be used to assess the impact and opportunities.

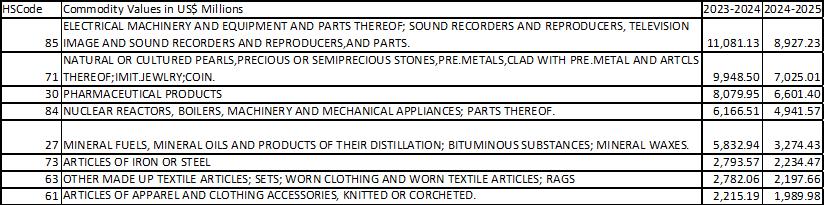

Table 1:

India’s export basket to the U.S.{million US $}

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry 2024-25 is from April to December.

The top five export commodities to the USA in FY 2023-24 were:

1. Electrical Machinery and Parts

Export Value: $11 Billion. Percentage of total Exports to the USA: 14.30%. Import intensity: 30% – 50%. Asian countries being the competitors, and, who are now at tariffs of between 35% – 54%, much higher than India.

2. Gems and Jewellery:

Export Value: Approximately $10 billion .Percentage of Total Exports to the USA: Approximately 12.9%. Import intensity: 60% – 80%

The value add that India does is to cut, polish, and set in jewellery. Again, South East Asian countries are the low cost competitors, and European countries are the higher value added competitors. Since India does more of the skilled labour intensive work, a slight advantage to EU countries will not shift trade.

3. Drugs and Pharmaceuticals:

Export Value: Approximately $9 billion. Percentage of Total Exports to the USA: Approximately 11.6% . Import Intensity: 60% – 80%

Pharma tariffs are yet to be disclosed by the U.S. India can utilise the PLI scheme to integrate backwards and make more of the input molecules, thereby controlling more of the value chain and costs.

4.Petroleum Products:

Export Value: $5.8 billion. Import intensity: 60% – 80%.

The uniqueness of Indian refiners is that they can process a variety of grades of crude. There are Asian competitors, but Indian refiners are efficient as per the Singapore GRM standard.

5. Textiles and Apparel (Including worn)

Export Value: $4.9 billion. Import Intensity: 30% – 50%,

On the exporting front, India competes with the likes of Bangladesh, Vietnam, etc. All competitors have been hit by much higher tariffs, so, in the short term, this should benefit India.

Conclusion

Based on our export composition, price elasticity, and import intensity, not all sectors are vulnerable to tariffs, Looking from the lens of elasticity, the inelastic segments like pharma are less vulnerable. However, gems and jewellery, and apparel are more sensitive to tariff decisions.

India has now got a small window of 1-3 years wherein it has got a slight advantage due to competing countries in Asia being charged higher tariffs. India can utilise this window to further buttress its export sectors. In this way, India can build up the global scale, cost competitiveness, and innovation required to scale up the export sector.

Today, the multipolar trade order is of robust economies that will not weaken but transform and create new value chains, and fresh opportunities of trade creation. Trade wars operate on a subtler tone, they create realignment and stir a search for catalytic transformation. Tariffs create barriers, but trade always finds a new road, roads that lead to economic progress and new trade partnerships.

About the author:

The authors Dr. Badrinarayan Gopalakrishnan is a fellow at Niti Aayog and Dr, Sarika Rachuri teaches at ICFAI Business School (IBS), Mumbai. Views expressed are personal.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited