This year’s economics “Nobel” prize (the quotes remind us that it is not one of the original prizes endowed by Alfred Nobel) is particularly satisfying for professional economists, and at the same time extraordinarily relevant for countries like India that seek to grow quickly but sustainably.

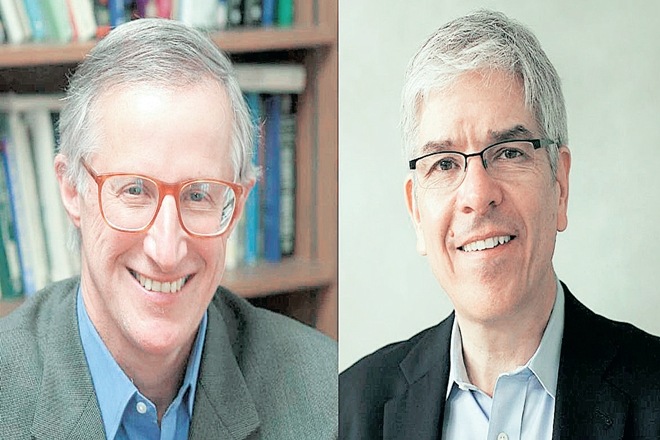

At first sight, the two awardees, William Nordhaus and Paul Romer, work on very different things. Nordhaus has spent most of his career building models that seek to quantify the economic costs and benefits of policies to deal with climate change and related environmental issues. Romer is best known for his work on the role of innovation in economic growth. The two economists were linked in the prize committee’s citation by their focus on long-run growth, or, as the committee put it, “long-run macroeconomic analysis.” Both of them sought to further the connection in their post-prize comments: Nordhaus mentioned his early work on innovation, and Romer pronounced on the importance of dealing with climate change.

Given the importance of technological change and climate change in the global economy, now and in the foreseeable future, rewarding work on these topics is obviously relevant. I return to that later in this column. What I want to highlight first is how the two prize recipients illustrate different, but equally important and complementary ways of doing economics. I think it is fair to say that Nordhaus has not given us any fundamentally new economic insights. In a post-announcement talk, he spoke of “side effects,” or, what economists call “externalities” or “spillovers.” The presence of these effects in climate change and a host of environmental issues means markets do not do an optimal job of resource allocation, and require difficult policy responses, especially when tackled at a global level. Nordhaus has spent decades building and refining large models that can use data from climate and other scientists to quantify costs and benefits of different economic policies, and guide policymakers. Building good empirical models is an important strain of work in the economics profession.

In my view, Romer’s contribution is quite different in style. He certainly looks at the data. But what it leads him to are sharp and deep insights into “how things work.” His original observation that knowledge, in the form of blueprints or instructions or formulas, introduces increasing returns to scale in an inescapable manner, at a stroke provided a rigorous answer to the puzzle that previous economic models of growth had posed—in those models, growth in output per capita would inevitably die out because of diminishing returns. Once innovations that add to our stock of knowledge are properly incorporated into descriptions of the production process, this puzzle goes away. Of course, Romer did more than provide a simple insight—he worked out its implications in many different kinds of economic situations, and provided at least qualitative guideposts for economic policy with respect to supporting innovation.

Nordhaus’s and Romer’s professional personas have also been different, matching the styles of their work. Nordhaus has been quiet and uncontroversial. Romer, on the other hand, has been bold in challenging conceptual models in international trade, but especially in macroeconomics, when he thinks that the model assumptions are so far removed from reality that the abstraction leads to misleading conclusions. He has taken on prominent American macroeconomists, including previous Nobelists, criticising them bluntly, and if the prize were decided in the United States, he might still be without one. Again, I think both kinds of approaches to professional engagement have value. Thus, this year’s prize illustrates the spectrum of methods and styles encompassed in modern economics, which remains an important endeavour, if always with scope for improvement.

Returning to relevance and connections, it is easy to make the case that innovation will be critical for dealing with issues such as climate change. If the question is, how can several billion people be raised to living standards that match those in economically developed regions, the answer is not just the general one fleshed out by Romer, that innovation must be sustained. This innovation has to be guided in directions that will lead to environmentally sustainable increases in the standard of living: lower carbon emissions, less air and water pollution, preservation of biodiversity, and so on.

Even perfectly competitive markets do not lead to optimal outcomes when there are spillovers—negative ones of environmental damage, positive ones of knowledge accumulation. Things are worse when producers have market power, which can hinder innovation or accelerate environmental degradation. Countries like India do not have the luxury of following the path taken by Europe or the United States in their economic growth, or even the path followed by Japan and Korea. Economic policies have to respond to current realities.

Of course, economists like Nordhaus and Romer can only provide conceptual and technical advice. Politicians have to have incentives that translate these inputs into good policies. Some of those incentives come from the choices of the voters. But voters have to understand the issues at stake. A large number of American voters did not have a good grasp of the issues with respect to technological change and environmental damage when they supported Donald Trump for president, and he continues to obfuscate reality in those areas. Can Indian voters do better? It will be good if they can.

The writer is Professor of Economics, University of California, Santa Cruz