By Hindol Sengupta

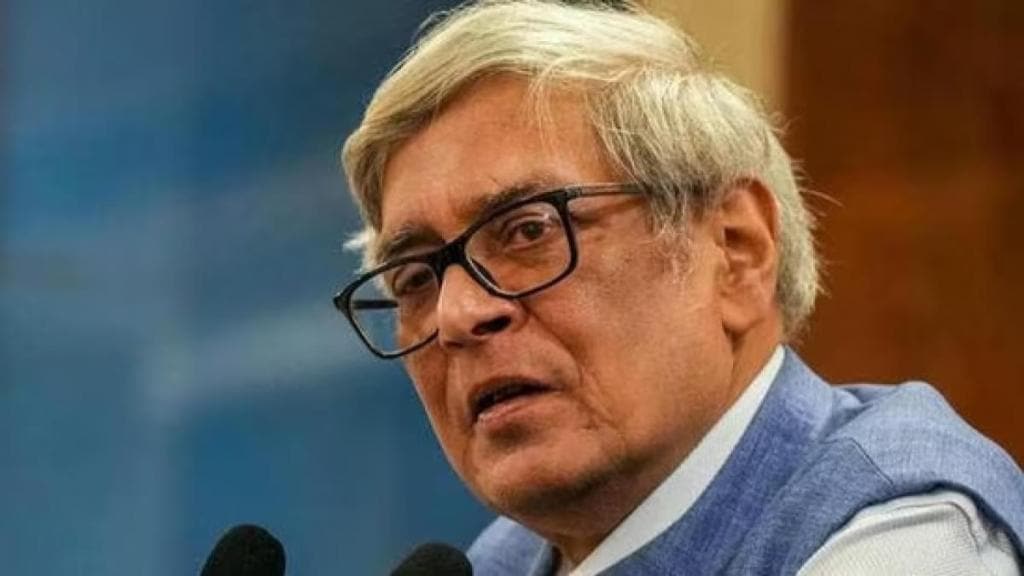

The first time I met Bibek Debroy, about 20 years, he scolded me for asking the wrong question about some arcane economic policy issue. What was it? I can no longer remember. But I remember the firm but polite tone. I was wrong, and I had to be taught the right way of thinking about the policy. That I was a young journalist had been forgotten; in that moment, I was firmly his student.

That is what I remained, always a bit scared of him, always a bit awed, even though over the years we became very familial. And what started as ‘Dr. Debroy’, became ‘Bibek-da’, and his wife, ‘Suparna-di’. There is no part of my life where I did not receive advice from Bibekda – from what to read, what to write, where to work, how to work, and even who to marry. It was a favourite pastime of Bibekda, and his childhood friend, the London-based former academic of the LSE, Gautam Sen, another mentor of mine, to corner me and disburse stern chastisement for failing to lose weight. In every way, Bibekda was a paternal figure to me, an elder brother I never had, a father-like figure, almost.

Also Read:Short of a requiem

Of all the people, I was most scared of his opinion on my books. When he liked Being Hindu he didn’t tell me. He tweeted to Dr. Arvind Virmani, saying that Hindol has written a good book. I spotted that and mustered up the courage to ask him for an endorsement for the next edition of the book.

He was the greatest Sanskrit scholar I have ever known, with the ability to recite, at will from memory, verse upon verse from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Puranas, what Bibek Debroy read, he never forgot. He was the only man who lived to translate both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and he was confident till the very end that he would finish translating all the Puranas. After a recent illness, over tea one day, he very precisely told Suparnadi and me exactly how many years he needed to complete all the Puranas. “At least till then, I am there.” When Bibekda said something, I blindly believed it. I had never known him to be wrong about anything, nor misquote any text. It seems devastating, and utterly unfair, that he was wrong about this timeline.

Also Read:Indian economy can touch $20 trillion by 2047: Debroy

When I joined Invest India, it was Bibekda and Suparnadi who I used to turn to for advice on everything – good days, bad days, and how to negotiate the labyrinth of government. And when that stint was done, it was he who reminded me, once again, as he had several times before, that a stint in academia would be useful. As always, I took his advice.

His home was one where I could go anytime. To have watched him do the Mahashivratri Puja was to recognise that, truly, Shiva is everything. My parents loved him. My mother thought he resembled a sage. “Apni to sothiyie sadhu-r moton, apnar proti amader onek bhokti (You are truly like a monk, we have great reverence for you),” she would say to him in Bengali. On such occasions, Bibekda merely smiled. But Suparnadi would say, “If it hadn’t been for me, your Bibekda would have no life. He would only be sitting and working.” She was absolutely right. Supardi made a dandy out of him, but he was always a bit aloof, even in a party. He was that valued Bengali character, what my mother calls, a “reserved gentleman”. Incredibly kind and generous to countless people, he was, however, never gregarious; there was always a sense that given half a chance, he would slip away into his study, and start working.

Who knew that the last book he published, Life, Death and the Ashtavakra Gita, would be co-written with me? At the launch of the book a few weeks ago, Bibekda announced that he and I were going to work on a series of new books. This was going to be the most exciting thing in my writerly journey and would take at least the next decade. I can lament and cry about how tragic and unfair this is, but as he wrote in his last column in this newspaper, perhaps like him, I took should take to heart the lessons of Ashtavakra, in Bibek Debroy’s translation, “Even when hopes are dashed, a great souled person’s mind has no desires and he is content with jnana about the atman.”

(Hindol Sengupta is a historian, and author, most recently, of Life, Death and the Ashtavakra Gita, co-written with the late Bibek Debroy.)

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.