By Atanu Biswas

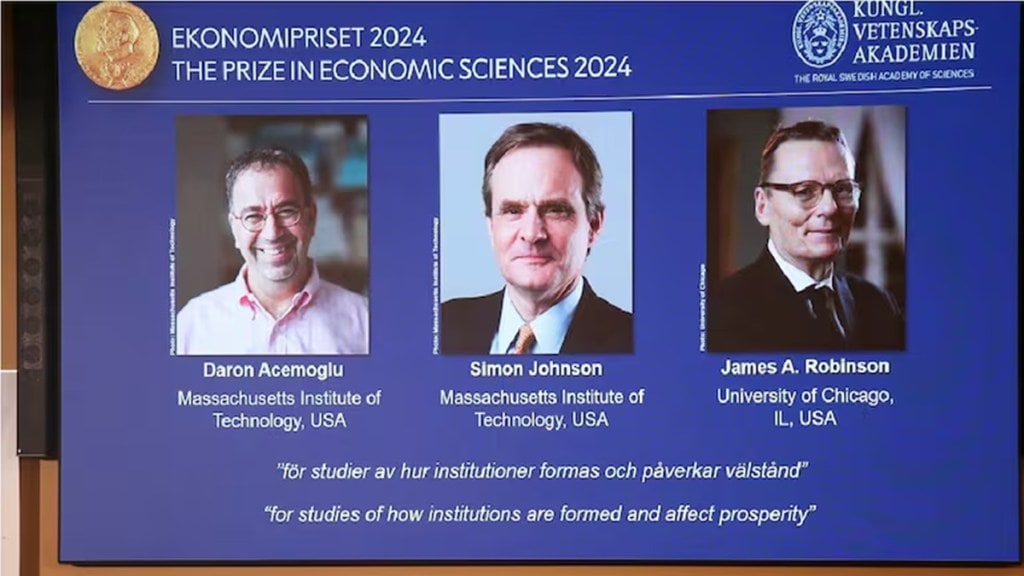

From Adam Smith to the contemporary randomistas, economists have looked for the key drivers of sustained growth. Given that this year’s Nobel Prize in Economics is awarded to Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Simon Johnson of Chicago University for their research on the long-term effects of various political and economic systems — particularly those established during colonialism — on a country’s prosperity, it may be worthwhile to revisit Acemoglu and Robinson’s 2012 book Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, which drew on this trio’s previous 15 years of research on the subject.

The authors contended that the causes of economic success — or lack thereof — and consequently, the current disparities in global wealth are not the often-mentioned factors like geography, climate, culture, religion, race, or the ignorance of political leaders, but rather our man-made political and economic institutions. Their theory pits two archetypes against one another: the so-called “extractive” and “inclusive” political and economic institutions, which both serve to strengthen and support one another. They argued that the majority of citizens can, among other things, benefit from safe property rights, have access to an independent legal system, and freely develop their personal skills because pluralistic political institutions offer an even playing field. These, in turn, promote technological innovation and economic activity. Political freedom then opens the door to prosperity. In contrast, extractive institutions have a disastrous effect on growth.

To create a new, very relevant theory of political economy, they examined a number of “natural experiments in historic examples”, including the Roman Empire, the Mayan city-states, the Soviet Union, the US, Africa, and the Glorious Revolution in Great Britain. They used the example of Botswana, which has become one of the fastest-growing countries, highlighting how violent and impoverished other African countries like Zimbabwe, the Congo, and Sierra Leone are. After gaining independence in 1966, Botswana was fortunate to have leaders dedicated to creating inclusive institutions and using the nation’s natural resources to fund initiatives that would enhance the welfare of the entire population.

Korea is yet another intriguing case. South Koreans are among the most affluent in the world, whereas North Koreans are among the poorest, despite the remarkable homogeneity of the two Koreas. The researchers claimed this is because of the political factors that gave rise to those two distinct institutional trajectories. They also looked at border cities, such as the divided city of Nogales, which straddles the US-Mexican border. Although the two halves share a relatively similar history, geography, population composition, and culture, the northern is over twice as wealthy as the southern.

These three researchers co-authored multiple highly-referenced academic papers, from which Why Nations Fail is mostly derived. Through their theory, they, however, challenged other explanations for global inequality, such as the geographical theory of Jared Diamond and Jeffrey Sachs, the theory of ignorance of the elites by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, the modernisation theory of Seymour Martin Lipset, and the various cultural theories of different experts.

Acemoglu and Robinson’s work, like Ian Morris’ Why the West Rules for Now and Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, addresses one of the most important issues facing humanity: why some nations are wealthy while others are impoverished? Crucially, Acemoglu and Robinson studied only the last few hundred years; thus, they had to exclude evidence from genetics, evolution, paleobiology, and archaeology. In contrast, Morris begins the development clock more than a million years ago, and Diamond starts it around 13,000 BCE.

The Nobel laureates’ work has also been criticised in different ways. According to Arvind Subramanian, it’s unable to account for the situations in China and India. India, which is democratic, has lagged behind China’s economic growth, which has been impressive under its authoritarian administration. Francis Fukuyama also makes it clear that their reasoning doesn’t hold true in contemporary China. But Acemoglu and Robinson retorted that since Deng Xiaoping’s opening-up programme was put into effect in 1978, political institutions have also contributed to economic change in China. For India, they contended that there are differences between electoral democracy and inclusive political institutions.

Fukuyama also noted that their treatment of Roman history is quite controversial. Also, Diamond has pointed out that they may be overlooking crucial elements such as “geography” in their explanation of economic development. The main issue with Why Nations Fail, according to Jeffrey Sachs, is that it concentrates too much on internal political structures while ignoring external variables like geopolitics and technological advancements (such as industrialisation and information technology). Furthermore, William Easterly argued that the transition from Mediterranean to Atlantic trade may have contributed to Venice’s collapse, despite Acemoglu and Robinson’s assertion that it was due to the city’s institutions having progressively become less inclusive.

Overall, the work of the Nobel laureates is, all things considered, audaciously ambitious in its simplicity of explanation for why some countries are wealthy while others are not. Therein lies the fundamental issue with “outliers”, which may be just as significant as China and India in this case. Actually, a country’s prosperity, like many other aspects of the economy, might depend on a wide range of intricately related factors, many of which are either immeasurable or not taken into account. Thus, as one may perceive, even though the Nobel laureates this year made an amazing effort to identify a few key drivers among them, other factors may still have an impact on their own, in combination with the others, or both. In general, any simpler model excluding those factors will appear more lucrative, but they’ll be more likely to have more outliers.

The author is the professor of statistics, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.