Imagine this. A building that resembles a modern tech lab more than a defence workshop, and engineers assemble around testing rigs and ruggedised boxes on a stretch outside Hyderabad.

A set of black metal units blink soundlessly with green and amber LEDs. There are no explosives, no loud sirens; just circuit boards humming through mock tests that mimic the stress of a battleground far beyond usual commercial environments.

These inconspicuous boxes are not ordinary electronics. In them lives the reasoning that tells a missile when to turn, a radar when to track, an unmanned aerial vehicle how to change in turbulence, and a launcher when to fire.

These are the “reactions” rooted within India’s defence systems, the split-second decision-making engines that make platforms intelligent and responsive.

This is Apollo Micro Systems, where decisions happen before movement begins.

A company that doesn’t build the weapon you see.

It builds the intelligence that makes it work.

Choosing the Invisible Layer in a Hardware-Obsessed Industry

Most defence firms draw attention because they own platforms, missiles, combat ships, and aircraft. Apollo Micro Systems chose a less conventional path: the digital and electronic connector tissue that orchestrates these machines with real-time decision systems.

In the early 2000s, when defence electronics in India were still fragmented and dominated by low-mix production, Apollo’s founders made a quietly bold choice.

Instead of chasing the bright lights of platform manufacturing, they focused on the embedded logic layer, the circuits and boards that interpret sensor inputs into actionable commands.

This space included rooted computing modules, command and control electronics, ruggedised hardware for severe environments, fire regulator automation logic, unmanned vehicle subsystems, defensive communication, and interface units.

In an industry where success is often measured by platform size or headline program wins, Apollo’s choice seemed unglamorous.

But it was strategic: platforms change, spec cycles differ, but the need for reliable, case-hardened logic processors stays stable.

As defence budgets and technology expectations have evolved, the power of this middle layer has gently become unquestionable.

Engineering for Failure That Cannot Be Allowed

In defence electronics, the natural environment is unforgiving.

Apollo’s components are designed not just to function, but to survive, in extreme heat, sub-zero cold, intense tremors, force, sand, seawater decay, and electromagnetic obstructions that would instantly deactivate commercial gear.

In the company’s testing labs today, you may find ruggedised units experiencing cycles impossible outside defence applications.

Thermal chamber exposure that veers more than 100°C, vibration tables that imitate launch and impact atmospheres, and electromagnetic interference/ compatibility (EMI/EMC) baths pushing signals to the edge of tolerance.

This is endurance engineering.

And Apollo manages every subsystem with a simple principle: if it cannot survive the hardest test, it shouldn’t be implemented in the field.

That rugged reliability is the reason Apollo’s systems find their way into rocket launchers and fire control units, frontline management and situational awareness systems, observation and scouting platforms, naval radar and combat systems, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and unmanned ground vehicles (UGV) control electronics, defence research and development organisation (DRDO) classified programmes, and tactical sensors.

These are not general-purpose microprocessors but battlefield decision processors. This level of survivability has become Apollo’s unique moat and its authority engine.

Why Integration, Not Scale, Became the Business Model

Apollo’s financial story makes sense only when seen through the lens of its integration-heavy model. Unlike defence primes that thrive on a few large, lumpy contracts, Apollo earns revenue through multiple smaller, high-value specialised orders.

Some of them are deep integration work with DRDO, Bharat Electronics Limited , and other Public Sector Units, long qualification and testing cycles, repeat upgrades, cascading lifespan replacements, and tailored subsystem projects involving hundreds of engineering hours.

In such a model, each project is not just a shipment but a portfolio of engineering work, and over time, that aggregate work turns into lasting revenue.

Recent numbers reflect this almost gravitational pull toward integration

The company posted a revenue of₹562 crore in FY25, an increase of 51% YoY compared to ₹372 crore in FY24. This surge shows the growth is built on complexity and system adoption, and not on volume.

The net profit of ~₹58 crore, excluding exceptional items in FY25, denoted that the company earned better margins as higher-value integrated systems contributed more than commodity boards.

The second quarter in FY26 saw a revenue of ~₹225 crores, a leap of ~40% YoY. The net profit was ₹33 crores, excluding exceptional items, marking a growth of 108% YoY.

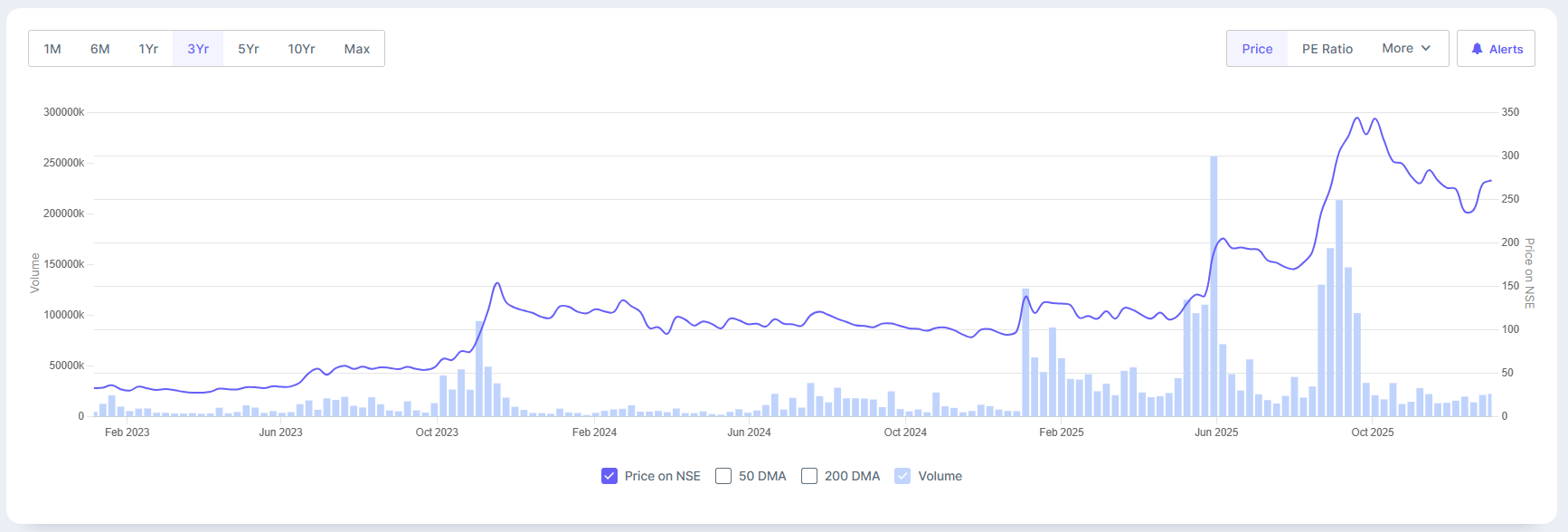

The profits grew at a compounded rate of 58% over the past three years. The return on equity was 8%, while the stock price grew at a CAGR of 105% during the same period.

Apollo Micro Systems 3-Year Share Price Trend

The improved returns on capital reflect an efficient use of capital regardless of the long development cycles inherent in defence electronics.

Moreover, Apollo Micro Systems has maintained a clean balance sheet. They have worked on controlling leverage, have minimal long-term debt, with a disciplined capital allocation.

Such a business model rewards reliability, not flash. It is not volume chasing. It is trust accumulating.

Apollo’s story isn’t about scale that would make it to the headlines; it’s about greater technical importance in every program it joins.

And the market seems to have considered this already. The P/E multiple stands at ~114x, trading at a premium compared to the sector median of ~61.4x. Its Enterprise value/ EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) at ~55x is higher than the median of ~34.3x.

The Advantage of Sitting Between Systems

Apollo’s tactical edge lies in its positioning between core platforms.

If you think of India’s defence architecture as a network, Astra Microwave builds the RF “ears”, Bharat Dynamics Limited builds striking mechanisms, Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd builds aerial platforms, Garden Reach Shipbuilders craft marine hulls, and Zen Technologies builds readiness environments.

Apollo builds their control and decision layer that allows these sections to work cohesively, just like the nervous system works in a body.

When a radar detects a threat, the command electronics decides how to arrange signals. When a drone enters a red zone, the embedded controllers determine how the platform responds.

When missiles launch in quick succession, timing decisions must run at microsecond speeds. Apollo’s control units, signal paths, and decision logic modules are the connectors that let these systems talk to each other constantly.

This is not just hardware. It is system intelligence.

Once a defence program adopts Apollo’s logic stack, replacing it later is costly, risky, and time-consuming.

That creates a natural moat, not protected by patents or unicorn valuations, but by permanent integration with platform lifecycles.

What Specialisation Demands in Return

Specialisation carries responsibilities.

Apollo’s revenues rely heavily on government programmes and defence PSUs. That may bring credibility, but it also creates dependency: programme breaks, or procurement changes, can momentarily pressurise execution timelines.

Electronics manufacturing, notably for defence, is working-capital heavy. Parts must be sourced long before the payments arrive, and certification cycles can stretch.

Technological changes in embedded systems are rapid. And modern warfare is increasingly combining AI, machine learning, neural network accelerators, and next-level sensor fusion.

Keeping pace means continuous investment in engineers who are fluent in these domains, which is a challenge in an industry where skill cannot be scripted, only earned.

Apollo’s risk isn’t competition. Its risk is the stability of expertise. It is about preserving knowledge while always pushing into new integration frontiers.

As Defence Turns Digital, the Middle Layer Becomes Central

India’s defence priorities are undoubtedly moving beyond raw hardware.

The future lies in encrypted tactical communications, integrated battlefield decision systems, autonomous and semi-autonomous platforms, networked sensors, weapons systems, and software-defined electronic warfare.

Every one of these hangs on electronics far cleverer than the blunt mechanics of steel and thrust.

That trend places companies like Apollo at the centre of the defence digitisation wave. Analysts are finally acknowledging what defence engineers have known for years: platforms are only as efficient as the logic that controls and coordinates them.

While headline narratives celebrate fighters or missiles, the real work of modern defence happens in the invisible layers, the reflexes that determine when and how machines act.

Apollo occupies that layer.

The Company That Times the Moment Everything Moves

Apollo Micro Systems does not build the weapon you see on TV.

It builds the timing unit inside it. The controller.

The rugged processor that refuses to fail at 40,000 feet or in 50°C desert heat.

The embedded logic that keeps a missile precise, radar responsive, or a battlefield node connected.

It is a company that grows in layers, not leaps.

A company that earns trust slowly, the only speed defence engineering allows.

And a company that will quietly become more important as India moves from mechanical warfare to electronic and networked warfare.

If Astra Microwave is the sense organ of India’s defence ecosystem, and Zen Technologies is the preparation engine, then Apollo Micro Systems is the nervous system, the part that ensures every command, decision, and reflex happens reliably.

And no modern army moves without a nervous system.

Disclaimer:

Note: We have relied on data from www.Screener.in throughout this article. Only in cases where the data was not available have we used an alternate, but widely used and accepted source of information.

The purpose of this article is only to share interesting charts, data points, and thought-provoking opinions. It is NOT a recommendation. If you wish to consider an investment, you are strongly advised to consult your advisor. This article is strictly for educative purposes only.

Archana Chettiar is a writer with over a decade of experience in storytelling and, in particular, investor education. In a previous assignment, at Equentis Wealth Advisory, she led innovation and communication initiatives. Here she focused her writing on stocks and other investment avenues that could empower her readers to make potentially better investment decisions.

Disclosure: The writer and her dependents do not hold the stocks discussed in this article.

The website managers, its employee(s), and contributors/writers/authors of articles have or may have an outstanding buy or sell position or holding in the securities, options on securities or other related investments of issuers and/or companies discussed therein. The content of the articles and the interpretation of data are solely the personal views of the contributors/ writers/authors. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their specific objectives, resources and only after consulting such independent advisors as may be necessary.