By SY Quraishi

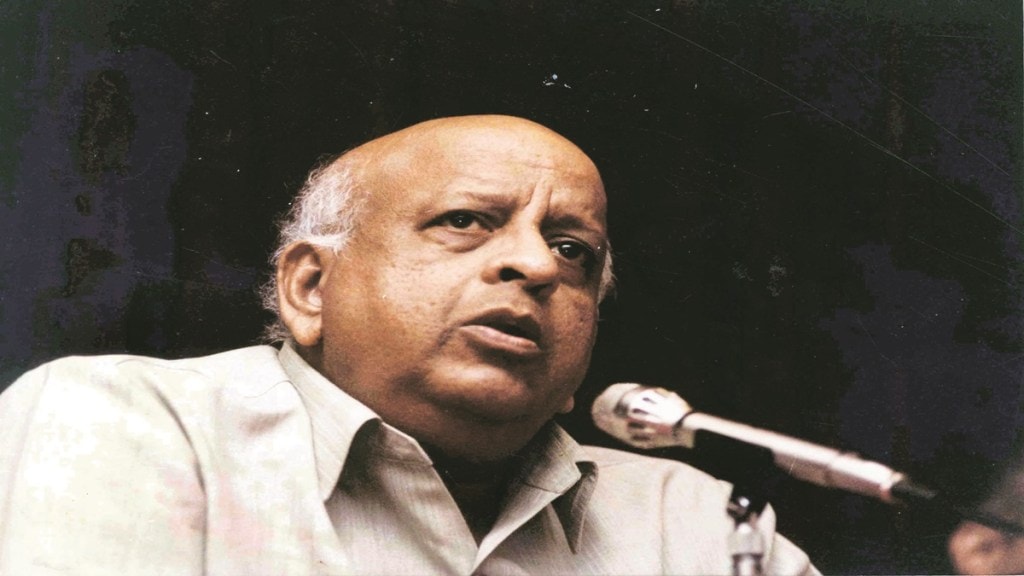

If there is one person who can be called a legend in his lifetime, it was undoubtedly Mr TN Seshan. His tenure as chief election commissioner of India is remembered as a glorious era of resurgence of democracy. The very mention of his name was enough to put the fear of god in the hearts of recalcitrant politicians, and respect in the heart of every Indian. I can say without hesitation that all of his successor CECs basked in his glory, though we always carried the burden of being compared with him. He took the commission to new heights of authority, credibility and visibility.

He realised that a battle had to be fought on all fronts to ensure that the Election Commission continued to be the watchdog of democracy which the Constitution expected it to be. The measures he took for cleaning up of electoral rolls, staggering elections, positioning security forces, annulling of elections won through wrong means, improving the counting processes, fine tuning media involvement in the election process, and counting of votes after mixing of ballots gave him a formidable image.

His autobiography, Through the Broken Glass, has been published four years after he passed away. I read it with great curiosity to know some known and unknown facts about his life and career.

There was nothing extraordinary about his childhood. He himself has said that childhood was all study, no play and a little work for him. Even in college, he was a disciplined student who did not bunk classes to go to the movies. He was fond of attending music festivals though. Like most civil servants, he taught in a college before joining service. His older brother, who was an IAS officer, served as inspiration. In 1954, he stood first in the IPS examination, but he didn’t join the IPS and decided to continue with his preparation for the IAS, securing a rank in the top ten. Maybe his dabbling in astrology was some help. For instance, he said he was not destined to have children, which proved true.

He describes his first posting as a sub-collector in great detail. There is some interesting information about the incarceration of Sheikh Abdullah during the Emergency in Madurai district, where he was collector for two years. A critical bit of information he shares is that the Congress government of Indira Gandhi and chief minister Kamaraj did not grasp the extent of dissatisfaction among the people owing to nonavailability of rice. This ordinary failure to provide rice to fair price shops, he claims, is what has kept the Congress out of power in the state for nearly 50 years now.

Describing his posting in the atomic energy department in Mumbai, he mentions that Homi Sethna, chairman of Atomic Energy Commission, gave generally favourable remarks in his annual confidential report, but added in the end, “he’s aggressive, abrasive and a bully to those under him”. The matter went up to Indira Gandhi, who questioned Seshan about these remarks and confronted Sethna in front of him. Although the remarks were expunged, it was a reputation that lasted his entire career.

Seshan refers rather fondly to Rajiv Gandhi who made him the cabinet secretary. Before that he was posted in the ministry of forest and environment. Later, he was also given the responsibility of protecting the PM, a job which he had never handled before. “You speak frankly. You do not fear anyone. Because of these qualities, I am giving you this job,” Rajiv had said.

Seshan mentioned that Rajiv had a great wish to be with the people. “Once in Calcutta when Rajiv had gone on an election tour, I had to run with the PM’s car for several miles to be present when Rajiv got off in anticipation of an excited crowd mobbing him. It was necessary for me to physically interpose between the crowd in the PM.” We had heard this as a rumour of his several questionable actions. Now, this totally unofficer-like behaviour stands authenticated.

Seshan was appointed CEC in November 1989. “I knew nothing about elections. I, anyway, did not think very highly of the CEC post,” he writes. Seshan mentions an interesting conversation with Rajiv Gandhi who said that Chandrasekhar will repent giving you this job.

Most of the book is about his tenure in the election commission. How he reformed the office, how he fought for electoral reforms and his constant fights with politicians. The most significant action taken by him to tame political parties was when he started countermanding elections that had not gone well. It seems half the time of Mr Seshan was spent in court cases. He describes several attempts to impeach him. One of these happened in connection with attending seer Paramacharya of Kanchi’s funeral when he borrowed Dhirubhai Ambani’s plane. He writes that he paid Rs 95,000 by cheque for this favour.

The fight he had with MS Gill and GVG Krishnamurthy, two newly-appointed election commissioners, takes a large part of the book. The title of chapter 12 is “Two more commissioners to share 15 minutes of work”. Surely, the quantum of work was not the issue, but dilution of dictatorial authority and style of the CEC, which even the Supreme Court ultimately upheld.

Where the EC functioned as a tribunal, differences emerged. “In one important case, the commissioners turned down my verdict through majority vote. By coincidence, it happened to be a case where the PM was involved. The wording of the case is in public domain and anyone can access both points of view.” The insinuation is clear. I wish he had mentioned the case.

Elsewhere in the book, he also makes an opposite point. “It is interesting to consider a hypothetical situation. Suppose I was the lone member of the commission and done the same thing in terms of exercising my powers. In such a situation was it not very likely that some people would have pounced on me, saying that I was being arbitrary, dictatorial, whimsical, among other things? But since there were three of us, there was little scope for their making such comments.”

Seshan quite honestly refers to the myriad of allegations against him, true or false, including stories that he was doing black magic!

Seshan mentions a New York Times article, which he describes as interesting though not entirely accurate. “ If a poll were taken to find India’s most admired personality, a strong candidate would be TN Seshan. And if a poll were taken to find a public figure Indians consider most high-handed, Mr Seshan would be a probable winner again. His major weakness may be his ego.” He quotes Vir Sanghavi’s description of him in the Blitz as a chamcha-turned-megalomaniac. He continues to poke fun at himself in these words, “I often say that Palakkad Brahmins come in four types: cooks, crooks, musicians or bureaucrats, and that I was all four of them.”

Commenting on the media, he said, several institutions in the country have fallen in standards. But the media is the worst in this respect.

Referring to two controversial decisions post-retirement, all he has to say is that he was “involved for some time; the presidential election of 1997 that I contested; the Lok Sabha elections of 1999”. He glosses over how this adversely affected his well-earned aura.

Mr Seshan was a colourful personality but the book doesn’t seem to capture the full palette. The reason could be that it was assembled by his former research assistant, Nixon Fernando, four years after his death. Despite this shortcoming, the book is an essential read for those interested in knowing about the great transformation of India’s phenomenal electoral and democratic processes.

Through The Broken Glass: An Autobiography

TN Seshan

Rupa Publications

Pp 368, Rs 795

The writer is former chief election commissioner of India and the author of An Undocumented Wonder: The Making of the Great Indian Election