Dayoung Lee and Gagandeep Nanda

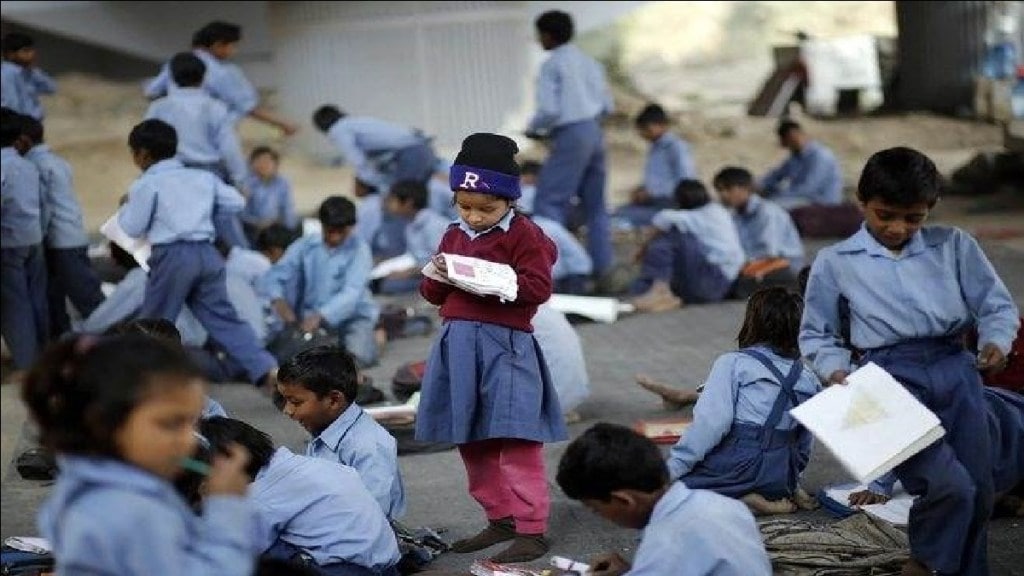

In May, the World Meteorological Organization predicted that global temperatures could breach the 1.5-degree Celsius limit between 2023 and 2027. It is the latest indication that the world is hurtling towards climate change faster than ever. Another study by journal Nature Sustainability further pegs this figure at 2.7C, with India being the worst-affected country. This could potentially push 600 million Indians outside the ‘climate niche’, the set of conditions within which a species can survive. As we tackle climate change, we must think about those who stand to lose the most. Children are least responsible for climate change, and yet the most likely to be affected in various ways. A 2022 UNICEF report found that about 80% Indian youth believe that their education has been impacted by climate change.

Globally, the conversation on climate change and education is picking up. Taking heed, in November 2022, a COP27 event sought to outline how education can address the world’s climate crisis. In December 2022, UNICEF too launched a $10B Appeal to reach 110 million children impacted by conflict, catastrophe, and climate change. To ensure that we can translate intent to action, we looked at two broad sets of strategies — adaptation and mitigation.

Adaptation: Devising effective workarounds

Climate disasters tend to have a direct bearing on infrastructure, resources, and the stability required for undisrupted education. In 2018, for instance, massive floods and landslides in Kerala impacted 1,613 schools, and 86,634 students lost their books, bags, and other learning material. And in 2019, Cyclone Fani in Odisha damaged 6,791 schools and the education department suffered a loss of Rs 417 crore.

Adaptation strategies help tackle immediate challenges posed by discontinuity in schooling. Innovative infrastructure, which accounts for local geography and existing infrastructure, can play a promising role. Take for instance Bangladesh’s floating schools, where children in flood-prone areas attend schools on solar-powered boats. These vessels pick up and drop students along the waterways of Rangpur, Rangamati, and Sirajganj, among others. The model, scaled to 500 schools since its inception in 2011, benefits 14,000 students a year.

Discontinuity in schooling also results in increased variation in learning levels amongst students. Adaptive learning, an approach that moves the focus away from standardised lesson plan delivery is one such solution. PAL (personalised and adaptive learning) software enables delivery of content that is customized as per the learning level of students rather, than as per the grade they are enrolled in.

Mitigation: Tackling the problem head-on

The second set of approaches aims to bring in systemic changes and address the long-term impacts of climate change through education. As a starting point, we must adopt a climate lens in curriculum delivered in education institutes. In September 2020, Italy mandated schools across the country to introduce Climate Change Education in their curriculum. South Korea had made a similar move. In India, while environmental education has been part of the curriculum since the 1980s, the development of climate action is hindered by technical content-heavy curriculums that do not necessarily have strong behaviour change components. Exposing students to climate discourse at an early age contributes to greater awareness, instils civic responsibility, and promotes climate-responsible behaviour. Additionally, it can emotionally prepare for future shocks caused by the crisis: A Lancet study revealed that about 75% of children think climate change has made the future frightening and 45% said that these thoughts interfere with their day-to-day functioning.

Higher education institutes can specifically develop curriculum to help students develop skills required for green jobs. GEO-6 for Youth, a digital guide by the United Nations Environmental Programme, identifies skill mismatch as a barrier to the shift towards green careers. Using education as a tool to drive strong, impactful messaging and encourage climate change innovation ventures can drive the youth to take charge within and outside their communities.

Another aspect for mitigation would be for educational institutes to look inwards and implement changes that make them move towards net-zero. The Chavara Darsan CMI Public School in Kerala has a bamboo forest on campus, uses LED lighting and solar panels, and pushes students to adopt carbon-neutral food habits. Institutes could also re-evaluate daily choices, such as investing in eco-friendly transportation, reducing usage of printed learning materials, and checking food wastage in cafeterias. State and national policies can support this by mandating educational institutes of suitable size to derive a certain percentage of their power from green sources.

While educational organisations and policymakers are the first in line for corrective action, funders and philanthropies can also drive research in this space, help education institutes assess their vulnerability to climate change, and support dissemination of knowledge and best practices. It is important for funding allocation to prioritise communities disproportionately impacted by climate change, such as girls, low-income households, and those residing in climate hotspots. Education is foundational to developing perspectives, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. For many, it is also a window to better jobs and opportunities. A stable and predictable climate is key to ensuring this happens. To account for this, it is imperative for the discourse around climate change to expand to include education.

Dayoung Lee is a Partner and leads the Education practice at Dalberg Advisors. Gagandeep Nanda, an Associate Partner at Dalberg Advisors co-leads the Education sector work in India