By Vivek Sharma

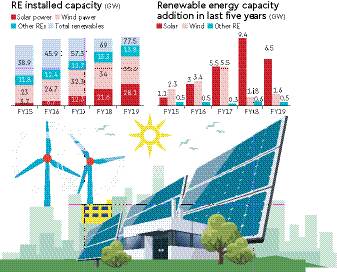

If India’s renewable energy (RE) sector is to shake off its torpor of the past couple of years, a complete revisit of its ecosystem, and an integrated approach to solutions is imperative. Indeed, over the past decade, the sector has seen significant growth in capacity – especially over the past five fiscals, after the government announced an ambitious target of installing 175 GW capacity by fiscal 2022, with installed capacity surging to ~78 GW (including ~28 GW solar and ~35 GW wind) in fiscal 2019 from ~39 GW as of fiscal 2015.

However, over the past 12-24 months, the sector’s prospects have come under a cloud – with wind capacity addition declining drastically since fiscal 2017 and solar capacity nearly screeching to a halt last fiscal after logging the maximum installations in fiscal 2018 (see chart). The reasons for the decline in growth are not far to seek. First is the tariff cap set in the auction process. It has skewed the economics even as the safeguard duty has increased costs and associated risks. Also, from a lender’s perspective, the most important requirement is a desired minimum debt service coverage ratio (DSCR), which is linked to the tariff quoted. In addition, past aggression means investors and lenders are risk-averse.

Second, despite assurances, land clearance and grid connectivity are hard to come by. This is causing delays in commissioning, inapplicability of quoted tariff for the commissioning year, cost overruns, penalties, and an eventual impact on project cash flows. The upshot is heightened risk perception among bidders, which could translate into higher tariffs.

Third, distribution companies (discoms), a de facto monopsony of RE buyers, are the weakest link in the chain. The health of most remains poor even as the Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana (UDAY) nears its end, and UDAY 2 looms. Outstanding dues of discoms to conventional power producers had increased by around 57% on-year to ~Rs 80,000 crore as of Oct 2019, heaping pressure on the RE sector also. Our analysis shows a six-month delay in payment impacts the equity internal rate of return of a project by 200 basis points. To be sure, initiatives have been taken by the government, including introduction of letters of credit, but it remains to be seen how these resonate with lenders/investors.

Fourth is the delay in adoption of tariffs. Ideally, tariffs discovered under competitive bidding should be adopted by default. However, there have been cases of substantial delays. The government notified recently that tariffs would be deemed to be adopted in case of a delay by state electricity regulatory commissions. While this should help mitigate risk to some extent, how this pans out needs to be seen.

Fifth is the infirm nature of RE. For discoms, one of the key concerns vis-a-vis RE is its inflexibility in syncing with peak demand. Therefore, another source is required to meet peak demand in the evening. Similarly, when solar or wind power is available, some other power source may have to back down. Both have a cost that someone must bear. Thus, a fair degree of grid integration is required to make it more viable for discoms to procure RE.

Sixth is the risk of curtailment. Discoms tend to curtail power, especially during off-peak hours or monsoons (when demand is more than the supply from RE sources) or when they have competing thermal power (where they are bound to pay fixed charges) available. While there have been notifications from the government to compensate for 100% of tie-up capacity, their enforcement is highly skewed on the relationship of distribution agencies and independent power producers (IPPs).

All this means the renewable energy target for FY22 looks distant. The government should, therefore, take steps to restore the faith of lenders and set the wheel of capacity addition whirring again. Three steps would be in order here:

1. Contract fidelity: Today, there is no guarantee contracts will be enforced. Cases in point are the recent move by Andhra Pradesh to renegotiate power purchase agreements and the UP government’s decision to stop buying wind power given a delay in tariff approval. Such practices have scarred the sector landscape and affected investments. Contracts should not be voided on the basis of political whims.

2. Alternative mechanisms for sale of power: Mechanisms to sell power in the open market should be promoted through policy and regulatory interventions. Sale of power through Green Term Ahead Market contracts (through exchanges) and open access (direct sale to the customer, with no cross-subsidy charges) need to be adopted and developed.

3. Market-based tariffs: Artificial tariff caps need to go and the market should get to decide tariffs based on costs and risks. Tariffs so arrived at should also be acceptable to the authorities and adopted by regulators automatically.

While these steps can go a long way, a true revival of the renewable energy sector will come about only with an overhaul of the distribution ecosystem in terms of tariff determination, subsidy disbursement, and governance structure, along with ease in land acquisition and availability of low-cost finance.

The writer is Senior Director – Energy, CRISIL Infrastructure Advisory