By – Raju Mansukhani

“If Nehru had died in 1958, history would have remembered him as the greatest statesman of the twentieth century.”In just a few words, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, summed up the paradox of Jawaharlal Nehru’s life and times. It may not have been an informed assessment, more of a casual remark by Lord Mountbatten when being interviewed by Sarvepalli Gopal, Nehru’s most erudite biographer in May 1970.

While Lord Mountbatten’s view on history and historical personalities will not be taken too seriously by many, undoubtedly 1958 was a landmark year in Nehru’s tenure as the first Prime Minister. The year has also become synonymous with marking, both the peak and the commencement, of a downhill trend in India’s relations with its friendly-brotherly neighbour China.

Nehru’s pronounced longstanding focus on foreign affairs, and his stature in world politics, is not a matter of hype but a historical fact. Sarvepalli Gopal felt that Nehru seemed to enjoy “the rare distinction of being of advantage to his own country as well as to the world.”

In the post-Second World War era, the process of disarmament was supremely important for Nehru. Through the 1950s he utilised his influence to give an impetus to disarmament and global peace besides non-alignment and the coming together of newly-independent colonies.

In January 1958, in his talks with British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, Prime Minister Nehru gave precedence to disarmament even over the contentious issue of Kashmir. Nehru agreed with the advice of the Defence Minister and UN Envoy VK Krishna Menon that France and Britain were opposed to talks on disarmament after the Disarmament Commission had broken up.

With the United States, Nehru had serious disagreements over disarmament and the creation of nuclear-free zones. The Americans were invariably perceiving Jawaharlal Nehru as a leader whose heart was beating for the Soviet Union and its model of socialism and industrial planning.

Non-alignment was another thorny issue making the Americans feel uncomfortable in dealing with Nehru. This did not stop President Eisenhower from writing to Nehru on 27 November 1959 in words worth recalling today: “Universally you are recognized as one of the most powerful influences for peace and conciliation in the world. I believe that because you are a world leader for peace in your individual capacity, as well as a representative of the largest of the neutral nations, your influence is particularly valuable in stemming the global drift toward cynicism, mutual suspicion, materialistic opportunism and, finally, disaster.”

Jawaharlal Nehru had been consistent in his intense involvement with international affairs. It is worth recalling that New Delhi – from 23 March to 2 April 1947 – had hosted the Asian Relations Conference. At a time when the political scenario in India was caught up in heated issues of Partition and Independence, Nehru became the prime mover of a conference that brought together China, Tibet, French Indo-China, North Vietnam, Palestine, Egypt, Arab League and the Soviet Republics like Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan among 28 other countries. Organized by the Indian Council of World Affairs, the conference aimed “to provide a cultural and intellectual revival, and social progress in Asia, independent of all questions of internal as well as international politics.”

Nehru’s position as a global leader was reaffirmed when non-alignment generated its own geo-political dynamics, raising concerns about the military confrontation between the world’s superpowers. By 1958, in a New Year message to a Soviet journal, it was only natural that Nehru pleaded for disarmament in progressive stages, with the ending of nuclear tests as a first step. At every opportunity, the Indian Prime Minister spoke of measures of control, with some forms of disarmament for the Western Powers.

Relations with China

The deterioration in relations with China, from 1958-59 onwards, has often made us overlook and disregard the Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai years which rang true from 1950 to 1955.

In 1950, India was the first non-socialist country to establish diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China.

In September 1951 Chou En-lai (Zhou Enlai) the first premier and head of government, had clearly stated while referring to the resolution of border issues between China, India, and Nepal, that “there was no territorial dispute or controversy between India and China”.

In Parliament and out of it, Nehru explained, “It was our belief that since our frontier was clear, there was no question of raising this issue by us.”

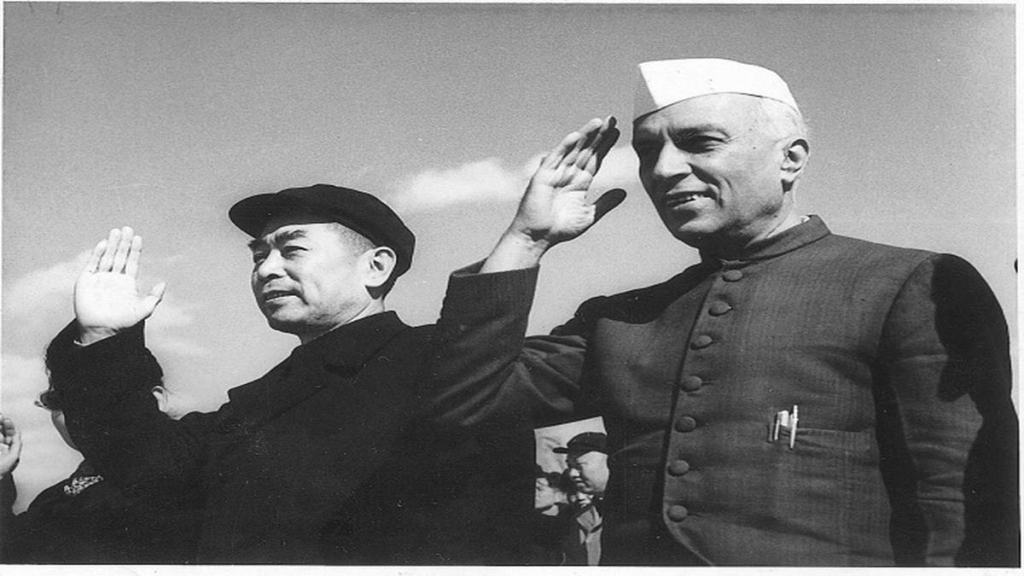

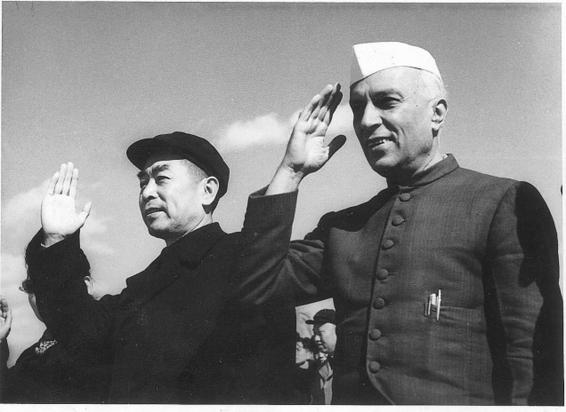

Then on 9 April 1954, the historic India-China Treaty was signed in New Delhi: it was an important milestone in India’s policy towards China. Zhou Enlai’s visit to India was widely covered and the air was filled with ‘bhai-bhai’ chants like never before. Photographs of the Indian and Chinese leaders capture their confidence and camaraderie.

In order to maintain friendly ties, Prime Minister Nehru agreed to ‘surrender’ all the political and commercial rights which India had enjoyed in Tibet in the British colonial period. Nehru’s biographers have underscored that the Prime Minister had no regret about this ‘surrender’ for it embarrassed him to lay claim to the succession of an imperial power that had pushed its way into Tibet.

Anxious to make the agreement purely non-political, the Chinese at first resisted mention of the Five Principles of Panchsheel, which they themselves had elaborated, but ultimately agreed to it as a concession.

A map in People’s China, on too small a scale to permit precision, showed the boundary with India as a settled one and roughly followed the alignment as depicted on Indian maps from Kashmir to Bhutan. Even in the eastern sector, while the delineation was unclear, no large territorial claims were made.

Nehru saw in this map further justification for not raising the border issue with China. He harbored no uncertainties regarding the Chinese diplomatic moves. He was also recognizing the Chinese sovereignty in Tibet since 1950 with a focus on the bigger picture of global peace.

Unshakeable Faith

Nehru’s faith in Chinese goodwill seemed unshakeable during the ‘Hindi Chini bhai bhai’ years.

His close associate, VK Krishna Menon wrote to Nehru after their meetings with Chou En-lai(Zhou Enlai) in Geneva: “Chou is a fine and I believe a great and able man. I do not believe that the Chinese have expansionist ideas . . . I found little difficulty in getting near him. He was never evasive with me even on difficult matters after the second day. He is extremely shrewd and observant, very Chinese but modern.”

After the India-China treaty was signed on June 25, 1954, Nehru spared no effort to urge the United Nations for the inclusion of China in the global body. It was a sign of his growing solidarity and friendship with China.

In 1954, Nehru’s visit to China was equally significant. He was the first head of a non-socialist country to visit China, and hold several meetings with Zhou Enlai to consolidate the Panchsheel agreement. During this visit on October 19, 1954Prime Minister Nehru met Mao Zedong in Beijing.

Ahead of the 60th anniversary of the Asian-African Conference convened in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955, China made public the minutes of the three meetings between Mao and Nehru in 1954. Imperialism was their common enemy; the United States and how it was shaping the post-war world were the common themes during their three meetings on October 19, October 23, and October 26, 1954.

The two leaders analysed changing power equations and the impact of World War II on global and Asian economies. Mao Zedong candidly admitted that China’s economic development was “lower” than that of India and it would take “ten to twenty” years for industrial development to achieve tangible results.

The records of these Mao-Nehru meetings are now available at the Digital Archive of the Wilson Center, Washington DC, providing unprecedented insights into the history of international relations and diplomacy, commented The Hindu in its report.

Nehru and Mao were openly discussing their ‘differences’. In fact, Mao mentioned to a Chinese, saying ‘to seize somebody’s pigtail’. He then said that India and China would not do that – seize each other’s pigtails. Nehru’s response was equally weighty and significant when he said, “Sometimes we have differences, but we do not quarrel.”

However, Nehru was determined to work with China and could not regard it as a potential foe. So, he continued to urge the United Nations to admit China. He also continued to reaffirm his confidence that India-China relations would remain friendly for the greater good of world peace.

(The author is a researcher-writer specialising in history and heritage issues, and a former deputy curator of the Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya.)

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position of the author’s institution or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.