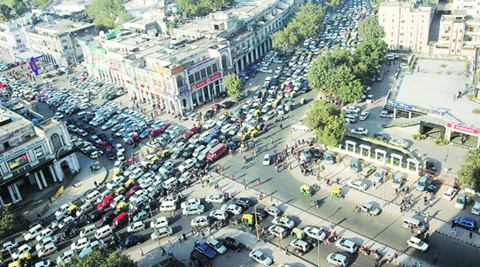

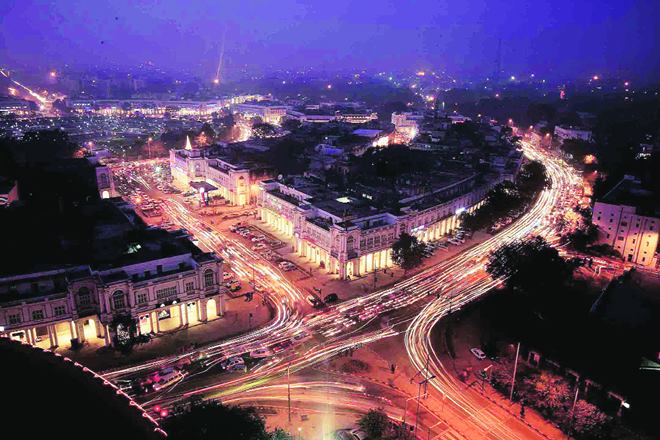

AFTER OVER a century of living with cars, some cities are now slowly realising that automobiles might not be the only answer to urban mobility. It isn’t just the pollution. In some urban centres, vehicles have turned out to be an inconvenient way of getting around, resulting in massive traffic jams. Unsurprisingly, several cities around the world are now getting rid of cars in certain areas through fines, better design and, in the case of Connaught Place in New Delhi, by proposing to make the area ‘car-free’.

Come February, and all roads leading to the central business district in the heart of the country’s capital will be barred for vehicular traffic. As per a three-month pilot project initiated by the Union urban development ministry in association with the New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) and Delhi traffic police, the inner and middle circles of Connaught Place will become ‘pedestrian-only’ zones—a move aimed at decongesting and reducing pollution in the area. Based on the feedback, the government could even make the arrangement permanent.

Connaught Place gets around five lakh visitors a day, as per reports. To ensure that the public is not put to too much inconvenience, arrangements have been made for ‘park-and-ride’ services. The locations for parking will be Shivaji Stadium, Baba Kharak Singh Marg and the Palika parking zone. Over 4,000 parking spaces are available in these locations cumulatively, as per reports. While environmentalists and some town planners have given the green signal to the plan, traders and a section of the populace have rubbished the idea, saying it would only result in further traffic jams, especially in the outer circle and the roads leading up to it, and adversely impact businesses of several commercial establishments in the area.

A step in the right direction

The idea involves much more than just stopping cars, feels Anumita Roy Chowdhury of the New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a not-for-profit public interest research and advocacy organisation. “It is about transforming our public spaces to improve the quality of life in the city. Imagine the attraction of open public spaces with aesthetic landscaping, public plazas, street festivals, street furniture and open gyms without automated wheels, honking and toxic killer fumes. These high-footfall areas will draw even bigger crowds, meaning more business,” says the executive director (research and advocacy) and head of the air pollution and clean transportation programme at CSE.

Roy Chowdhury refers to the successful cases in India, where cities have earmarked areas for pedestrianisation, to prove her point. “The trend has set in India, especially in old congested city areas or around monuments of heritage importance. The most successful cases are from the hill towns of India,” she says. Shimla, for instance, has the longest pedestrian road in the world, at 14 km. The central Mall Road in the capital city of Himachal Pradesh has been fully pedestrianised, as per the Shimla Road Users and Pedestrians (Public Safety and Convenience) Act, 2007.

Mahatma Gandhi Marg in the heart of Sikkim’s capital city, Gangtok, is another example. The vehicle-free zone allows unhindered indulgence for pedestrians. Gangtok also has designated pedestrian sidewalks and walkways, and traffic is strictly monitored with deterrent fines for overtaking and speeding on narrow hill roads. “In Punjab and Haryana, the high court has directed each city to have a minimum of one car-free zone. Dhobi Bazar in Bathinda, a central trading hub, is car-free. The traders themselves came forward to make it vehicle-free. There are several such examples. The Golden Temple precinct and its surrounding area (in Amritsar, Punjab) are vehicle-free. Several trades now thrive in the pedestrian zone. Similarly, Charminar in Hyderabad and the central commercial district, Paltan Bazaar, in Dehradun have been identified to become vehicle-free too,” adds Roy Chowdhury.

As per Sohinder Gill, director of corporate affairs, Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles (SMEV), an electric vehicles industry body, the drive to make Connaught Place car-free is positive and could become a game-changer for the entire ecosystem. “The pedestrianisation of CP would lead to the creation of a safe and clean environment, and evolve into a successful model for other cities to emulate and live by,” he explains, adding, “The people of Delhi are facing the air pollution menace, which has attained alarming levels, and are expecting the government to undertake some urgent action. Appropriate development of strategies for smoother implementation will surely help this drive go a long way.”

Though the government will disallow vehicles to enter the core areas of Connaught Place, electric vehicles (EVs) will not be restricted. In this regard, the SMEV has already shown interest in partnering with the authorities concerned. “The required infrastructure can be jointly built to facilitate easy mobility of EVs. This would ensure the smooth and sustainable transformation of CP into being a pedestrians’ delight,” adds Gill.

Speed-breakers ahead

The Connaught Place ‘car-free’ proposal, however, has not gone down well among a section of the populace, especially traders of the area. “This is not feasible. CP is a commercial centre, not a tourist destination. The moment inner and middle circles become vehicle-free, the outer circle will be choked. We already saw such a scenario on International Yoga Day (on June 21),” says Atul Bhargava, president of the New Delhi Traders’ Association (NDTA), which looks after the interests of commercial establishments in Connaught Place.

“Prima facie, one is sceptical about the step, assuming that it will directly impact footfalls in the market,” says Pooja K Sood, business head of Sports Station, a chain of multi-brand sports stores that has an outlet in Connaught Place. “However, the impact will depend on how well traffic and parking are managed in the outer areas of CP. If this move does not cause traffic chaos or increased parking time, the impact will be minimal. However, if it leads to traffic jams in the outer circle and at the parking spots, consumers will definitely choose to avoid shopping at CP, and this will adversely affect business,” she says. “We can’t expect everybody who uses a car to start travelling by Metro or any other public transport, especially to shop at CP. The government should calculate the parking space that will be required to ease the extra pressure on the outer circle of CP. They should also calculate the increased traffic in the outer circle. On the basis of these calculations, they should make the required parking provisions. If they are unable to anticipate correctly the extra load on the outer circle, business will get hampered and this may not prove to be a sustainable measure,” says Sood.

Eminent historian Swapna Liddle, who is also the co-convenor of the Delhi chapter of the not-for-profit Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), poses a few questions: “In the absence of cars, will a 60-year-old woman coming to shop at CP be happy to lug shopping bags for long distances? Will a young woman coming out of a bar or restaurant late at night be safe walking to a nearby parking lot where her car might be parked? Or will these people prefer to go somewhere else? In that case, what will happen to the retail outlets and restaurants? If they become unviable and start to close, Connaught Place will eventually get run down. It is, after all, a market and survives on commerce.”

Pre-modern cities were built primarily for walking and they were compact, explains Liddle. “In Old Delhi, for instance, the streets are, by and large, narrow. To take the example of a shopping area, one end of Dariba Kalan to another is 400 m, and from Dariba Kalan to Paranthe Wali Gali via Kinari Bazar is 350 m.”

By contrast, modern cities like New Delhi have been built in the age of the motor car and were designed suitably, says Liddle. “They are much more spread out. Therefore, the scale of Connaught Place is huge. If you want to watch a movie at Plaza and then eat at Barbeque Nation, you will have to walk 800 m. If you want to buy clothes and would like to visit a variety of shops, you will find that they are scattered over a huge radius,” she adds.

Proceed, but with caution

The idea is to proceed with caution, many feel. “It’s important to improve pedestrian facilities and public transport in the city as a whole. If that slows down car traffic, let it happen. It will automatically make using a car less pleasant. But before the facilities are upgraded, banning cars in important markets like CP will not be a good idea,” says Liddle.

Anshuman Malik, chief operating officer of Lebanese restaurant chain Zizo, which has an outlet in Connaught Place, says it would work, provided the administration rolls it out in a planned way. “Additional measures that would be required are allocation of extra parking spaces in outer circle, more drop-off points with traffic-control measures, safety of pedestrians, provision for seating spaces for the elderly and kids, among others,” he says.

To make a bigger difference to the environment, the government should launch campaigns involving community engagement towards the protection of Indian heritage and monuments, says documentary filmmaker Arjun Pandey, founder of Delhipedia, a location-based video guide for the city of Delhi. “The adoption of e-vehicles could prove to be a great contribution towards a pollution-free environment. The government must encourage their use and extend subsidies. Proper recycling of waste and better and stricter implementation of campaigns like Swachh Bharat Abhiyan could also add to the cause,” he says.

Caught in traffic

Vehicles are turning out to be an inconvenient way of getting around in several cities across the world

London traffic moves slower than an average cyclist or horse-drawn carriage

Drivers spend 106 days of their lives looking for parking spots in the UK, as per a study

Commuters spend up to 90 hours a year stuck in traffic in Los Angeles, as per a study

Globally in vogue

Globally, car-free zones are gaining in popularity. Some examples

Times Square, New York

Camden Street, London

Boulevard Saint Laurent, Montreal, Canada

The Vatican, Italy

The central district of Copenhagen, Denmark

Leading the way

How other Indian cities have successfully implemented car-free initiatives…

Up to 14 km of Mall Road in Shimla has been protected and reserved for pedestrians

Mahatma Gandhi Marg in Gangtok, Sikkim, is a vehicle-free zone; the city also has designated pedestrian sidewalks and walkways

Dhobi Bazaar in Bathinda, Punjab, is a car-free zone

The Golden Temple precinct and its surrounding areas in Amritsar are vehicle-free