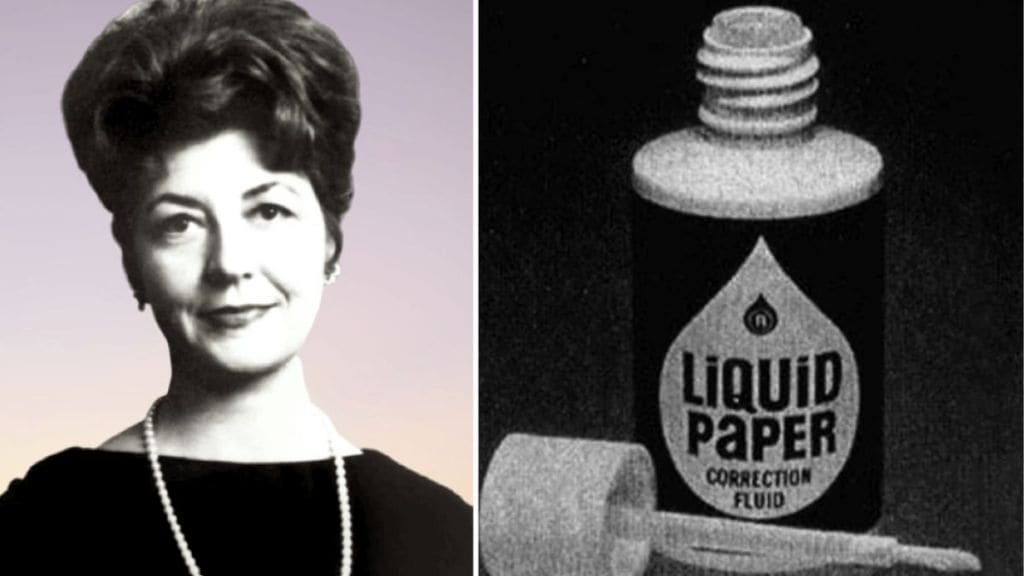

Bette Nesmith Graham’s name may not ring bells for everyone, but her invention, Liquid Paper, has been a staple of office supplies for decades.

Graham is a woman of remarkable creativity and resilience, and her journey from struggling single mother to self-made millionaire tells us a story of resilience and perseverance.

Who is Bette Nesmith Graham?

Born Bette Claire McMurray on March 23, 1924, in Dallas, Texas, Bette was raised in a modest family where her mother ran a knitting store and taught her to paint.

Her father worked at an auto parts store, and while Bette’s early life was far from glamorous, it laid the foundation for her later success.

At 17, Bette left school to marry her childhood sweetheart, Warren Nesmith, a soldier who went off to World War II.

While he was away, Bette gave birth to their son, Michael Nesmith, who would later achieve fame as a member of The Monkees.

After her marriage ended in divorce in 1946, Bette was left to support her young son. She took a series of odd jobs, from learning shorthand and typing to working as an executive secretary.

But the real challenge came when she found herself unable to keep up with the increasing demands of her job, specifically the limitations of her typewriter.

The typo that led to an invention

In 1951, Bette landed a secretarial job at Texas Bank & Trust in Dallas. It was there that she began to feel the frustration of making frequent typing mistakes on the new typewriters with carbon ribbons.

Erasers no longer worked without smudging the paper, and Bette needed a way to correct her errors quickly and efficiently.

Drawing from her artistic background, Bette had an idea: What if she could paint over the mistakes, just as artists did on canvas?

She took a bottle of white tempera paint, coloured it to match her stationery, and used a watercolor brush to cover up her errors. Her colleagues took notice, and soon, other secretaries in the building were asking her for some of the concoction.

Building the Mistake Out company

By 1956, Bette had refined her formula and began selling it to other secretaries in her office building.

She called her invention ‘Mistake Out,’ and even though she could not afford the $400 to trademark the name, she continued perfecting her creation in her kitchen. She consulted with a paint company employee and a chemistry teacher to improve the formula.

While the business was small, it was enough to pay the bills, and as the years went by, Bette’s side hustle grew.

She eventually enlisted the help of her son, Michael, and his friends, paying them $1 an hour to help fill bottles and slap labels on them by hand.

Yet, despite her efforts, the business remained a small operation with limited resources.

The turning point came in 1958 when Bette accidentally signed a bank document with the name of her side business, Mistake Out. This slip-up led to her firing, but it also gave her the freedom to devote herself to her business full-time.

After changing the name to “Liquid Paper” and applying for a patent, Bette’s small operation began to gain traction.

In the early 1960s, she secured major clients, including General Electric and IBM, which helped elevate Liquid Paper from a modest side hustle to a legitimate business.

By 1967, the company was generating significant revenue, and in 1975, Bette sold 25 million bottles of Liquid Paper in a single year.

Bette’s personal life

Robert Graham, her husband, became increasingly involved in the business, and their relationship soured.

In 1975, they divorced, but the power struggle over Liquid Paper only intensified. Robert tried to wrest control of the company from her, and Bette was eventually barred from making decisions.

In 1979, Bette sold Liquid Paper to Gillette for a staggering $47.5 million. Although she lost control over the company she had built, her royalty rights were restored. Sadly, just six months later, Bette died unexpectedly from a stroke at the age of 56.

Her son, Michael Nesmith, inherited his mother’s estate and took over her charitable foundations, continuing to share her story. “She built it into a big multimillion-dollar international corporation,” he said in a 1983 interview. “And she saved the lives of a lot of secretaries.”