By Amit Dholakia, Professor and head, Department of Political Science, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda

Fifty years ago, at 8:05 am on May 18, 1974, the tranquillity of the arid village of Lokhari, situated near Pokhran test range in the Thar Desert of Rajasthan, was shaken by the detonation of a nuclear explosive device, positioned approximately seven metres beneath the ground. The device exhibited a hexagonal cross-section, measuring 1.25 metres in diameter, and weighing 1,400 kilograms. Its design was of the implosion type, bearing a resemblance to the American nuclear bomb, the Fat Man, which devastated Nagasaki during World War II.

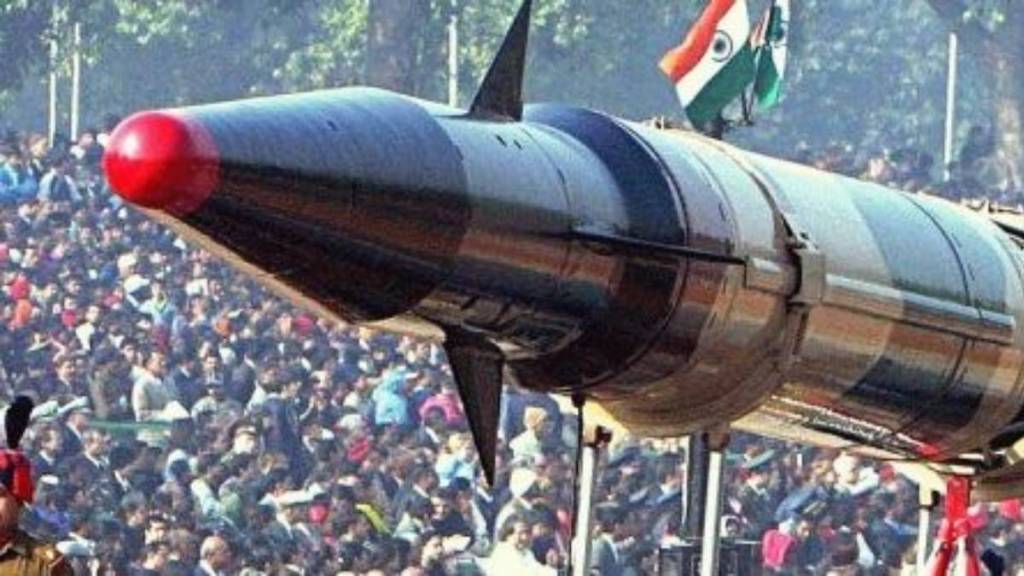

This event was codenamed Operation Smiling Buddha by the government of India. It marked the first nuclear test by a country outside the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. Operation Smiling Buddha represented a crucial milestone in the evolution of India’s nuclear programme and instilled a sense of pride in its scientific, technological, and military capabilities. Although the ministry of external affairs characterised this test as a “peaceful nuclear explosion” (PNE) intended for research to harness nuclear energy for economic development, this event was integrally linked with a series of five nuclear tests, codenamed Operation Shakti, conducted at again at Pokhran in May 1998 which officially established India’s status as a nuclear state.

India’s scientific community exerted multidimensional and strenuous efforts to make the Buddha smile on May 18, 1974. The inception of India’s nuclear programme can be traced back to Homi Bhabha, justly regarded as its founding father. His preparations began even prior to India’s independence and before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1944, Bhabha proposed the establishment of a nuclear research institute to the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust. This proposal came to fruition in the form of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in December 1945. Following Independence, the Nehru government established the Indian Atomic Energy Commission in 1948. It was followed by the creation of the department of atomic energy in the Union ministry, with Bhabha appointed as its first secretary, reporting directly to the Prime Minister.

The 1950s saw the rapid establishment of the Apsara and CIRUS reactors, facilitated by assistance from the UK, US, and Canada. Nehru also approved the first nuclear power plant at Tarapur. While there is no authoritative public chronology or definitive document about the decision-making process of the government on the 1974 nuclear explosion, fragments of information from the scientists involved in the project suggest that it took seven years, from 1967 to 1974, for India to prepare for the test. Then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi provided explicit directives to the scientific and defence establishments to keep India’s nuclear options open and to conduct a test when necessary. The process involved several critical steps: acquisition of fissile material (specifically, plutonium), design of an explosive device, fabrication and assembly of the device’s components, completion of a neutron initiator, preparation of the test site, and the placement of post-explosion diagnostic instruments. The project employed a limited team of 75 scientists and engineers to maintain secrecy.

Following Bhabha’s demise in a plane crash in 1966, several scientists oversaw the preparations leading to Operation Smiling Buddha. These included Vikram Sarabhai, Raja Ramanna, PK Iyengar, Homi Sethna, R Chidambaram, and BD Nagchaudhuri. PN Dhar and PN Haksar, who were close advisors to the Prime Minister, defence minister Jagjivan Ram and army chief Gopal Gurunath, also played significant roles in the decision-making process steered by Indira Gandhi.

The scientific and security community engaged with the nuclear programme had commenced serious deliberations for India’s nuclear test immediately after China’s atomic bomb test in 1964. The nuclearisation of China, which had seized substantial portions of Indian territory in 1962, posed a direct threat to India’s security and sovereignty. The threat was not merely territorial but also ideological, as Mao Zedong fostered the subversive Naxal movement.

The pressure exerted by the great powers on India to sign the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which aimed to perpetuate a discriminatory and unequal nuclear status quo by privileging the P5 countries, coupled with the threatening stance of the US against India during the Bangladesh war, intensified India’s resolve to develop a full-scale nuclear capability. India’s decisive victory in the Bangladesh war and its dominance in South Asian geopolitics necessitated an assertion of nuclear ambitions.

The rapprochement between the US and China, facilitated by Henry Kissinger in the early 1970s, exacerbated India’s vulnerabilities to external threats. The reclamation of India’s lost prestige as a regional power and an emerging global actor constituted a major driving force behind the 1974 test. Besides, when Indira Gandhi’s government faced massive domestic unrest, and protests, the test helped her government garner some popularity and legitimacy.

India’s nuclear test prompted a shift in the great powers’ strategy on handling nuclear materials. They instituted more stringent procedures and safeguards to oversee nuclear exports and supplies. Consequently, India experienced nearly three decades of isolation from the global nuclear technology and supply regime until the restrictions were eased following the ratification of the Indo-US civil nuclear deal in 2008 by the US Congress.

Aware of the gap between tests and weaponisation of nuclear capability, and short of delivery systems, India adopted a nuanced strategic stance in the post-PNE period. It maintained a policy of deliberate ambiguity and ambivalence while vouching for its moral and political commitment to the peaceful utilisation of nuclear energy and nuclear disarmament.