A serious crisis of electrical power shortage has the potential to derail the plan to vault the economy into a high-growth phase, unless the sector witnesses massive investments in the short term. During the recent days of scorching summer, the peak demand for power overshot all projections, nudging close to a staggering 250 gigawatt (Gw). The government had to forcefully put even the stranded gas-based plants on stream to boost supplies, yet the demand-supply balance was dangerously tenuous during peak hours. That there are enough buyers for the hugely expensive gas-based power is proof that the situation is already grim. With the demand expected to rise by 5-6% or at higher rates over the next five-six years, things could go awry even with a minor slippage in the short-to-medium-term plan for rapid capacity addition. Such an eventuality would have enormous economy-wide costs.

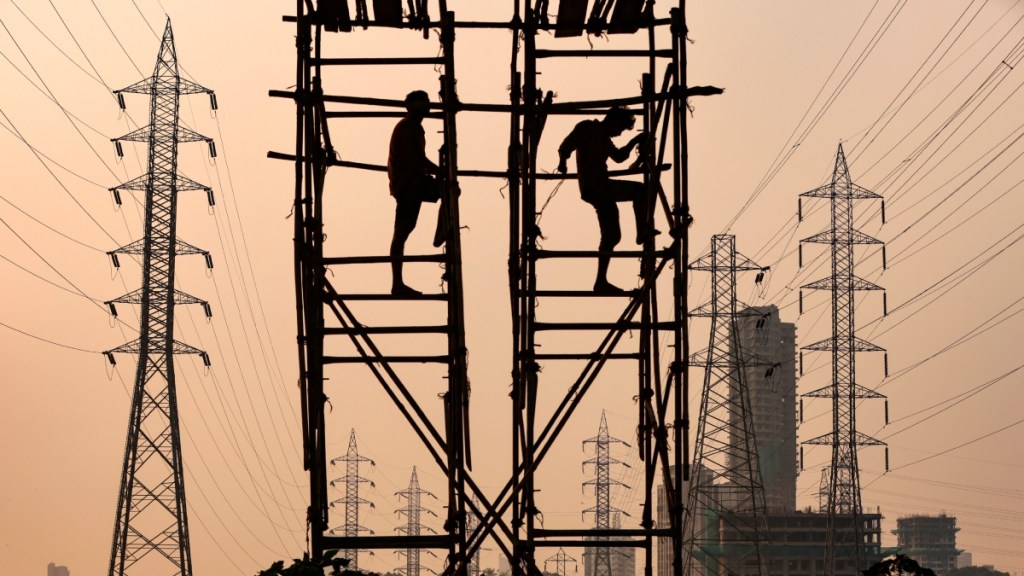

Thankfully, the Modi 2.0 government was quick to put a contingency plan in place. Another 35 Gw of coal-based capacity is being added to the 50 Gw that was in the works, and retirement/re-purposing of old coal-based stations has been put off. Also, the pace of renewable energy (RE) capacity creation is largely being sustained despite a few hiccups, although the ambitious target of 500 Gw by 2030 still looks daunting. Renewed efforts are being made to attract large-scale private investments into transmission and distribution (T&D), so that RE power is optimally shipped to demand centres. This shows the policymakers recognise that the key is to cut wastage of RE.

Currently, RE power is 43% of the installed capacity, but actual supplies are still less than a quarter, due to the intermittent nature of such energy. According to the Central Electricity Authority’s estimate, India would require 60.6 Gw of energy storage capacity by 2030, up from minuscule levels now. While investors are wary about battery energy storage systems, the government seeks to enthuse them with a 40% viability gap funding. Moreover, the latest tariff regulations (2024-29) have brought about more certainty about the rate of returns from each business segment, and allowed almost seamless cost pass-through, keeping investor interest in mind. There is also a new regulatory stiffness in dealing with payment defaults.

Given all this, and the composite planning for the sector that has been under way over the last few years, the new government’s decision to divide the portfolio between two Cabinet ministers — Manohar Lal Khattar for thermal-plus-T&D and Pralhad Joshi for RE — is a bit puzzling. This is an artificial separation, when the industry is naturally interconnected, and almost every major player seeks to straddle multiple areas. State-run NTPC, for instance, eyes RE capacity of 60 Gw by 2032, sharply up from 3.6 Gw at present, plans to double its coal output in three years, and is aggressive on nuclear power. Joshi, as minister for RE, would have to rely heavily on how Khattar consolidates the T&D segment, with massive investments. The stored RE would reach the consumer only if the grid has enough capacity to handle the load without much frequency alterations. Though some don’t see it as a problem as the two departments always functioned separately with two secretaries, the fact is that a common minister in the previous government played the role of an effective coordinator. Somebody has to play that role in this government in the interest of common goals — energy security and affordability.