By Karan Singh, Former Chief Secretary, Government of Punjab

On August 27, the US imposed reciprocal tariffs of 50% on Indian exports. While the first tranche of 25% was enforced on August 7, citing the US’s trade deficit with India, an additional 25% was explicitly linked to India’s continued procurement of Russian oil. Together, these duties have now come into effect, substantially increasing the tariff burden on Indian exports and placing them at a disadvantage compared to regional competitors such as China, Vietnam, and Thailand.

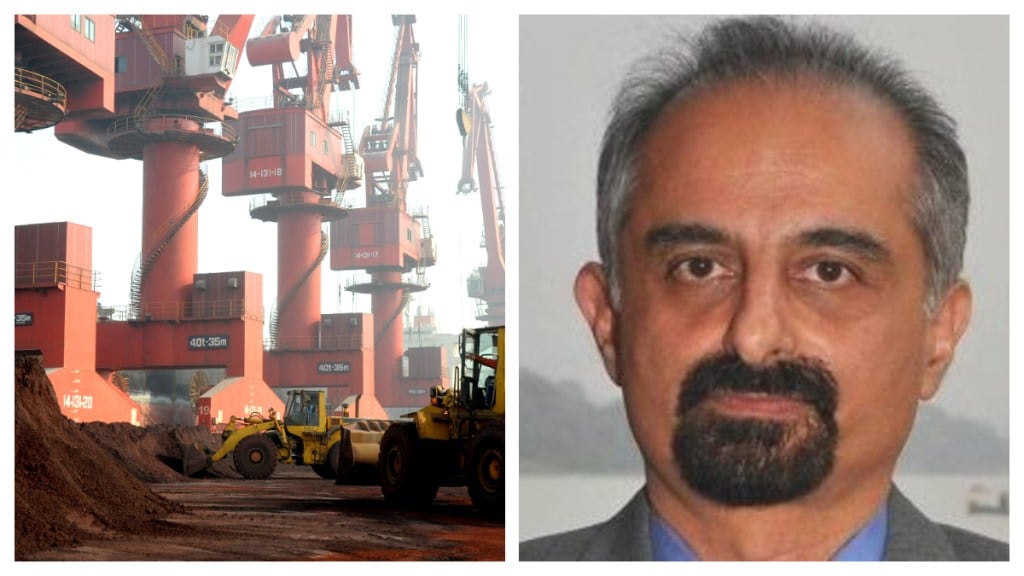

While broad categories of Indian products have been subjected to higher tariffs, certain inputs critical to the US economy have been exempted from any tariffs. One such example is baryte—a seemingly low-profile mineral, but one that is indispensable to the US oil and gas industry. The decision to exempt barytes reflects a calculated recognition of its importance to sustaining the US’s energy exploration programme. Despite holding extensive reserves domestically (close to 150 million tonnes), the US continues to import barytes consistently to preserve its own stockpile. By contrast, India has less than 23 million tonnes of reserves left, yet we continue to export aggressively, accounting for nearly 48% of total US baryte imports.

Baryte mineral plays a foundational role in hydrocarbon exploration, particularly in offshore drilling. It is used in drilling muds to stabilise boreholes, control formation pressures, and prevent blowouts. For deep-water operations, there are no technically viable substitutes. In practice, the availability of barytes determines the safety and feasibility of modern oil and gas exploration. The US has recognised this and ensured uninterrupted access as part of its energy security planning.

India, on the other hand, has continued to treat barytes as an ordinary export commodity. Nearly 96% of India’s barytes exports are directed to the US, despite India’s finite reserve base being heavily concentrated in a single deposit at Mangampet in Andhra Pradesh. With annual extraction averaging 2.5-3 million tonnes, current reserves could be exhausted within the next decade. Continued large-scale exports, particularly to a trade partner that is simultaneously imposing punitive tariffs on India, directly undermines our long-term energy interests. This asymmetry illustrates the wider problem with India’s resource management.

Other major producers have adopted a more strategic approach. Since 2013, China has restricted baryte exports to safeguard domestic availability. The US, Russia, and Iran—major oil-producing nations—do not export barytes at scale. India, in effect, has emerged as the world’s primary supplier, filling a critical gap in the US supply chain. But this has come at the cost of depleting a strategic resource, without yielding reciprocal gains in trade negotiations, and instead exposing India to unprecedented tariff actions.

China has repeatedly leveraged its export of rare earth magnets and other critical minerals to influence trade negotiations and secure favourable outcomes. India could potentially adopt a similar approach by leveraging export restrictions on barytes.

Strategic roadmap for future trade negotiations

As nearly half of the US’s baryte imports is from India, the US is significantly dependent on Indian barytes to keep its oil and gas industry running. Placing barytes under the restricted export list, capping volumes in line with reserve forecasts, and mandating end-use declarations would ensure that exports continue in manageable volumes, while it contributes to India securing acceptable reciprocal concessions that serve our long-term strategic objectives. This is precisely what China has done with its rare-earth magnets and other critical minerals. Even a calibrated restriction, rather than a complete ban, would send a strong signal that India recognises barytes as a strategic asset and intends to deploy it judiciously in the national interest.

India’s strategic mineral base extends beyond barytes to rare earth resources such as monazite deposits containing neodymium, praseodymium, cerium, and lanthanum, elements critical for clean energy, electronics, and defence applications. By safeguarding both barytes and rare earths, and developing domestic value chains around them, India can strengthen its negotiating position in global trade and reduce the risk of geo-economic arm-twisting by external powers.

Processing of rare earths for use in India and for export of value-added products will add to our bargaining power. A long-term growth strategy must combine conservation along with investing in downstream value addition. Exploration of new deposits alone will not be enough.

Our export policy must be aligned with the same principle that guides our oil procurement strategy: resources critical to national security should be deployed carefully, not given away unconditionally. As global trade becomes increasingly fragmented and interest-driven, India must recognise the true cost of exporting strategic minerals and place their value at the core of trade negotiations. Without such a shift, countries like the US will continue to secure their future by drawing down our stockpiles, while we undermine our own industrial security in exchange for short-term export revenues.