The Reserve Bank of India’s mandate is price stability. However, it has joined other central banks in adapting its mandate to the objective of sustainable growth. It is therefore helpful when the RBI lays out a path for the growth of the economy — a duty often lost sight of by the government of the day that is focused on political goals.

All the information that is available points to a period of slow growth in the world economy and in India. The essay in RBI’s Bulletin (July 2023) on State of the Economy has, referring to the world economy, acknowledged that “global growth momentum appears to be stalling, especially manufacturing and investment. International trade is also showing the knock-on effects of re-engineering of supply chains through muscular industrial and trade policies. Once again, the world’s constituents are set on diverging paths…”

On the Indian economy, the Bulletin lists the progress and achievements: upgraded infrastructure, digitalisation, solar generating capacity, exports of services, favourable demographics, ebullient equity markets, etc. Some claims under each head are true. The Bulletin also notes the sequential moderation in economic activity, high unemployment rate, uptick in demand for work under MGNREGS, contraction in manufacturing exports, contraction in revenue expenditure, decline in net tax collections, increase in CPI (and food) inflation, hardening domestic bond and corporate bond yields, and unending fight against inflation.

There are always pluses and minuses. Despite the mixed picture, India’s GDP (at constant prices) achieved an average growth rate per year of 8.5% during the five-year period 2004-2009 and 7.5% during the ten-year period 2004-2014. On the contrary, the average growth rate per year in the nine-year period 2014-2023 has been 5.7%.

Why has the average growth rate slumped? Growth rates are boosted in the initial years of liberalisation and market-oriented policies. Steroids — stimulus packages — help boost the growth rate. The benefits of unconventional monetary policies, adopted in the United States and Europe to offset the global financial crisis and the pandemic, flow to developing nations like India. In normal times, however, it is the attention paid to structural deficiencies and measures to remove them that will ensure high economic growth.

In my view, the present government has neglected some fundamental weaknesses of the economy. Here are four:

Low Labour Participation Rate and High Unemployment: The working age population (15 years and older) of India is estimated at about 61% of the total population — that is 840 million. It will decline after 2036. The celebrated ‘demographic dividend’ has a short life. The bugbear is the Labour Participation Rate (LPR). In June 2023, it fell below 40% (against China’s LPR of 67%). Female LPR is worse at 32.8%. Why are 60% of the working-age population (men and women) and 67.2 per cent of women not working or looking for employment? Now, apply the unemployment rate of 8.5% to the LPR. (Unemployment rate of age 15 to 24 is 24%). You will get an idea of the enormity of un-utilised human resources. Increase in life expectancy and the spread of education are of no use if a full 60% is not able or willing to work. The Indian economy is running on two of four wheels.

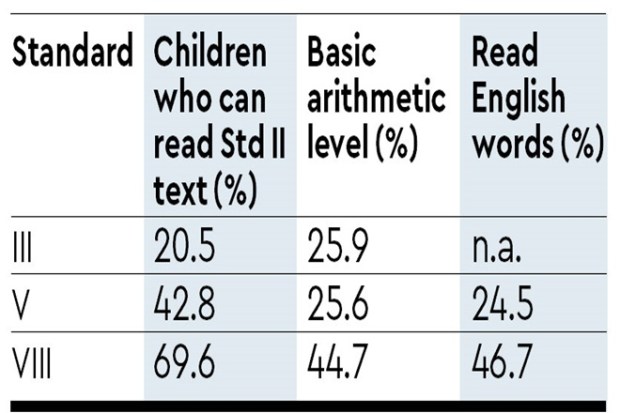

Quality of Education: The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) is a nationwide household survey that captures, among other things, the learning outcomes of children in rural India. ASER 2022 reached almost all rural districts. Here is a summary of the findings on learning levels in reading, arithmetic and English:

There are also huge variations among states. The average years of schooling in India is 7-8 years. If these are the learning outcomes of our children in numeracy and literacy, how do we teach our children and skill them to take on jobs/responsibilities that require higher levels of learning and technology?

Low Productivity in Agriculture: According to the Economic Survey 2022-23, India’s rice yield was 2,718-3,521 kg per hectare while wheat yield was 3,507 kg per hectare. China’s yield per hectare (2022) was reportedly 6,500 kg of rice and 5,800 kg of wheat. That India has become an exporter of rice and wheat may have induced complacency. Going forward, climate change, migration to cities, urbanisation, water availability, and rising input costs will mean that, if farming must remain a worthwhile and profitable activity, productivity per hectare must increase.

Inflation and interest rates: Indian industry is competing to survive amidst high inflation, high interest rates (because of perceived high risk of lending) and high tariffs. All of them must be tackled vigorously and lowered.

When did you hear the Hon’ble Prime Minister or the Ministers concerned speak on these structural deficiencies? Never?

Do we want India’s economy to grow at over 7.5% so that we may become a middle-income country or do we want to trudge along at 5-6% and boast that India is the fastest growing large economy in the world? The latter is the equivalent of being ‘the one-eyed monarch of the blind’.