By Anita Inder Singh

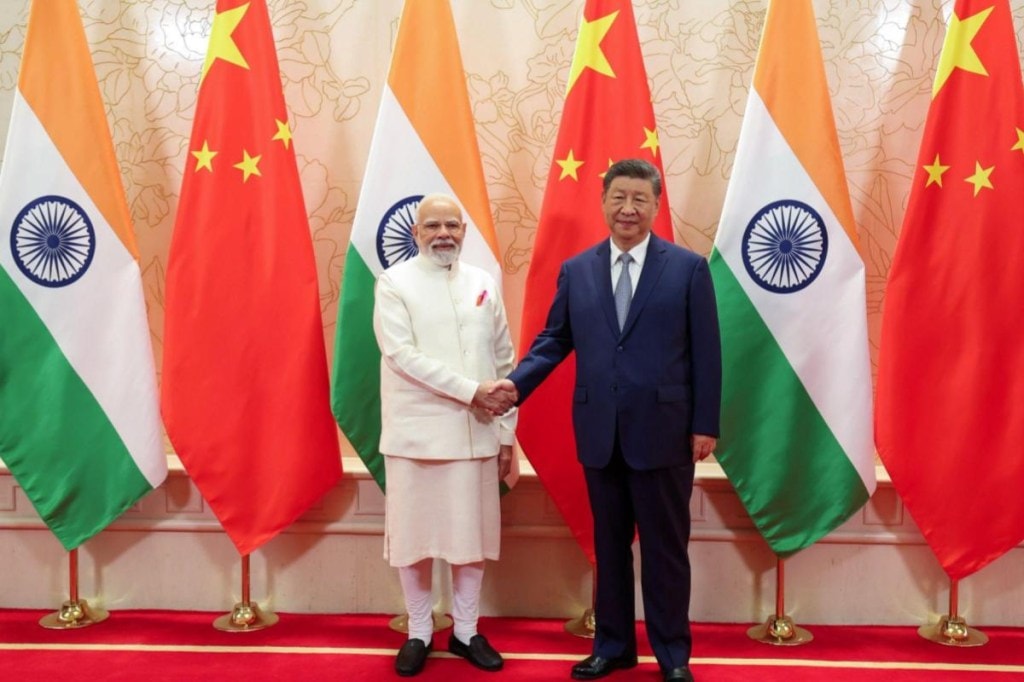

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Tianjin, a major port in northern China, from August 31 to September 1 is the largest-ever in history. It is taking place as the world faces a Trumpian trade and tariff war, which is destabilising the global financial system. Additionally, as America disrupts the world and cuts aid to the United Nations (UN), the outstanding guest is UN Secretary-General António Guterres who has hailed China as a cornerstone in defending multilateralism. President Xi Jinping, in turn, has assured him that China is a “reliable partner” to the UN. Xi has already met several leaders from Asia, Europe, and Africa, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi who are attending the summit. To Modi, Xi has stressed that their countries should be rivals not partners. A “cooperative pas de deux of the dragon and the elephant” should be the right choice for the two countries, he said.

As India confronts the full force of Trump’s trade assault, Modi has asserted that India is committed to strengthening bilateral ties based on trust, respect, and sensitivity.

Together with other member-states, China aims to present a rival front to America’s globally disruptive practices.

The rise of the SCO as a geopolitical bloc

Initially conceived as a security organisation with an anti-US flavour after the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the SCO grew from a group comprising China, Russia, and Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan in 1996 to manage border security issues. The continuing strength of the Sino-Russian ties was obvious prior to the summit as diesel-electric submarines from the Russian and Chinese navies carried out their first-ever joint underwater patrol in the Asia-Pacific. India, which hopes to strengthen its relationships with China and Russia because of Trump’s tariff warfare, should dispel any illusions that it can be a priority for either in the wake of Trump’s punishing levies.

During its 29-year development, the SCO has grown into a Eurasian bloc representing nearly half of the world’s population, a quarter of the global landmass, and a quarter of global GDP. With the accession of India, Pakistan, Iran, and Belarus, the SCO now has 10 member states, alongside two observer states and 14 dialogue partners.

According to Beijing, the so-called Shanghai Spirit includes mutual trust, equality, respect for diverse civilisations, and pursuit of common development.

India’s weak hand at the SCO

The summit is also showcasing China’s economic power. Official Chinese sources claim that the SCO’s share of global trade with other members rose from 5.4% in 2001 to 17.5% in 2020. In 2024, China’s trade with other SCO members touched a new high of $890 billion and 14.4% of its total foreign trade.

For India, the summit has come at a fateful moment as it faces 50% tariffs on its exports to America. India’s attempts to increase trade with an expansionist China as an alternative to the US, despite their enduring border conflict, have attracted some domestic and international criticism. But they have been welcomed by China which sees the tariffs and the SCO as an opportunity to drive a wedge between New Delhi and Washington. An anti-America China welcomes a new partnership which could manage China-India friction over their border dispute while increasing trade. Simultaneously, a transactional China perceives Modi’s attendance as an opportunity keep India in its place.

India has been a latecomer to the SCO as a full member (2017), so its contributions are limited. The 2020 Galwan clashes with China explain to some extent why it has tended to shrug off the SCO. Its presidency of the 2023 summit was reduced to a two-hour virtual meeting. Modi avoided the 2024 summit in Kazakhstan. The meeting between Modi and Xi in Tianjin has taken place after seven years, in the wake of the disruption caused to Asia by Trump. So, Modi has travelled to the summit with a relatively weak hand.

India would gain little by trying to make a big issue of anti-terrorism as it attempted in 2024. While counter-terrorism is an SCO priority, China will not allow any move that tries to place Pakistan on the terrorist agenda. In June, India refused to sign an SCO defence ministers’ agreement because it omitted the Pakistan-organised Pahalgam militant attack. Pakistan is also a milestone on China’s Belt-and-Road Initiative, and among its largest arms buyers.

If the SCO and better relations with China are to enhance India’s reputation and role, New Delhi should pay more attention to issues including the modernisation of economies and societies than to traditional medicine and Buddhism, which will not enable New Delhi to influence a diverse group of countries, tested by Trump’s global crisis-manufacturing.

The main focus area of the SCO is Central Asia, where India is on the periphery. Unable to counter China convincingly even in its immediate Indian Ocean neighbourhood, India should avoid boasting about its grand strategies for strengthening ties with a distant Central Asia. After all, China initiated the inclusion of both Central and South Asia under the SCO framework.

President Trump‘s tariff attack on India underlines that Washington is no longer cultivating New Delhi as a hedge against a stronger and more assertive China. However, India must play its political and economic cards very carefully as it makes moves to China to counter the adverse effects of Trump’s tariffs on its exports.

It remains to be seen how easily Delhi will take some ground-breaking initiatives so that India and China relations can establish peace along their disputed border.

Finally, will the SCO summit transcend ideological and social differences to create, in China’s words, “a new type of international relations”?

The writer is founding professor, Centre for Peace and Conflict Resolution.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of FinancialExpress.com. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.