What did the people of Ghazipur make of the massive new factory that quickly came to dominate their old and historic town?

It is impossible to say. As is so often the case with colonial India, there is very little to go on in terms of sources in Indian languages. Everything that is known about the Ghazipur Opium Factory comes from documents written in English; according to a leading contemporary expert nothing has ever been written about the two opium factories in Bhojpuri or Hindi: ‘not even a short story’.

This silence is largely due, no doubt, to the fact that the factories were even more intensely racialized than most British colonial institutions.

***

The Indians who worked in the Opium Department’s factories were under constant surveillance; and, as Kipling notes, they were subject to frequent searches. Indeed, the measures designed to prevent pilferage were so extreme that the workers were sometimes not only searched but also washed before they left the premises. This indignity was visited most often on the hundreds of young boys in the workforce: this was intended to prevent them from pinching opium by rubbing it on their bodies and then getting washed down at the bazaar, a method of pilferage that was said to fetch 4 annas per washing.

This distrust of Indians would surely also have extended to local visitors, which is probably why there are no descriptions of the factory in Hindi or Bhojpuri. White travellers, on the other hand, were not only welcomed but also encouraged to visit. Over time the Patna and Ghazipur factory complexes even became a part of ‘the Grand Tour of India’ and were featured in many English guide books.

***

One Indian who could certainly have visited the Ghazipur Opium Factory was Kipling’s contemporary and fellow Nobel Laureate, the poet Rabindranath Tagore, who spent six months in Ghazipur, living in a bungalow that had been found for him by a relative of his who worked in the factory. During his stay, Tagore and his wife were visited by several relations, including his sister, the writer Swarnakumari Devi, who later composed a long piece about her stay in Ghazipur. Their bungalow was close to the factory and through their relative the Tagores met many of the local Bengali residents, most of whom would have been employees of the Opium Department.

***

One day, finding themselves near an indigo factory, they almost went in but were repelled by the stench. The odour around the Opium Factory, they were told, was even worse.

Whether for this reason or not, the Tagores never visited the Opium Factory, even though, as Swarnakumari Devi notes, they could very well have done so. But evidently the factory inspired a kind of revulsion in them: seven years earlier, at the tender age of nineteen, Rabindranath Tagore had published a searing indictment of the colonial opium trade, titled ‘The Death Traffic in China’.

***

The distaste that is evident in this passage probably derived from Tagore’s guilty awareness that his own grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore, had traded in opium, and had even petitioned the colonial government for a share of the reparations that China was forced to pay after the First Opium War. The poet would return to this subject again and again over his lifetime.

The contrast in the attitudes of Kipling and Tagore, two Nobel Laureates who were almost exact contemporaries, is itself a commentary on the differences in the perspectives of colonizer and colonized: on one side there is a smugly complacent acceptance of a manufacturing complex that produces enormous revenues for the colonial state, and on the other there is an aversion that seems to want to erase the factory by not referring to it in writing.

Fortunately, records of a different kind do exist and they present the divergent perceptions of colonizer and colonized even more vividly than would be the case with a written description. These records consist of three sets of images of the Patna Factory, one made by an Englishman and the others by Indians. By far the best known of these images is a set of six coloured lithographs made by an officer in the British colonial army, Captain Walter Stanhope Sherwill. The prints were displayed at an exhibition at London’s Crystal Palace in 1851 and were later published as a bound volume, titled Illustrations of the Mode of Preparing the Indian Opium Intended for the Chinese Market. They have since been widely reproduced, usually much reduced in size, and in black and white, rather than colour.

Having long been familiar with the reproductions, I was taken by surprise when I first saw an original copy of Sherwill’s prints. They were much larger and more detailed than I had expected, and the colours were unexpectedly vivid.

The overall effect was startling: the prints gave the Patna factory the monumental dimensions of a cathedral, or an Egyptian temple, with towering ceilings, majestic columns and long shelves that converged upon perspectival vanishing points. Among the human figures, those that were drawn to scale were mainly the white supervisors, who are shown to be leaning casually against the walls as they keep watch over the workers.

The Indian figures seem shrunken and gnome-like: bare-bodied men treading in vats of raw opium and boys scuttling between enormous storage shelves. Yet, instead of producing an impression of verisimilitude, the profusion of detail and the geometrical lines have quite the opposite effect: they make the factory look like a stage-set, a fantasy.

***

As the art historian Hope Childers observes, the prints were ‘tailored to reassure metropolitan visitors at the Crystal Palace that industrial progress was being made in the colony’.

‘Progress’ was indeed the god who reigned over the temple that Sherwill depicted in his prints of the Patna Opium Factory. The images were akin to votive offerings for the deity: a god for whom periodic exhibitions of industries and machinery served as festivals of adoration. Hence the imposing interiors and the suggestion of mechanized production, as in the textile factories of Birmingham and Manchester. Sherwill’s prints were a kind of paean to the Industrial Revolution and the machinery that made it possible.

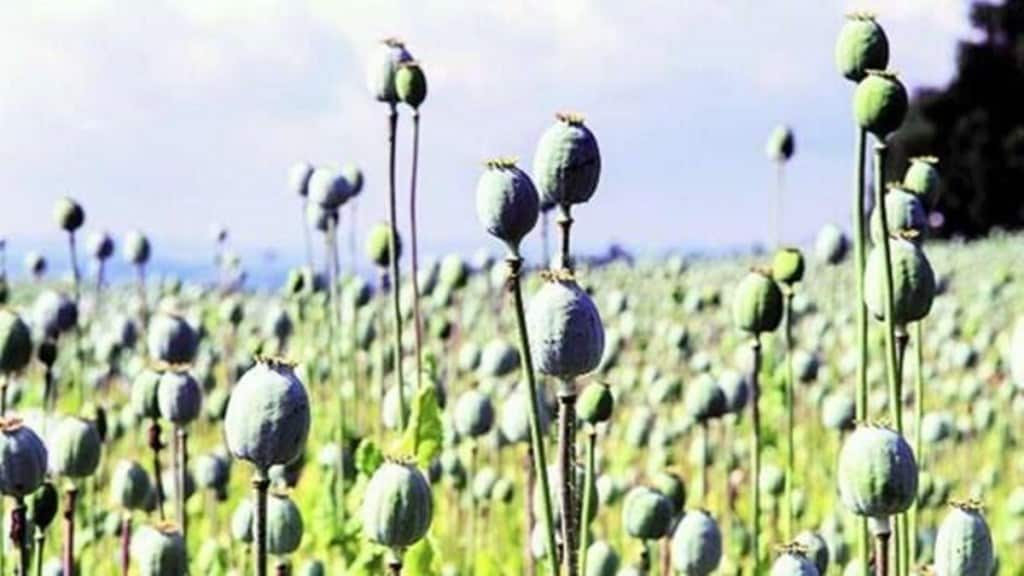

The trouble, however, is that in the opium factories of Ghazipur and Patna machines were conspicuous by their absence. The processing of opium was done entirely by hand, and foot. Barefoot workers spent as much as ten hours a day tramping up and down long vats of raw opium. The fumes were so heavy that they often became sleepy and lethargic.

***

Far from being clean, Euclidean spaces, the factory’s interiors were crowded, hot and cramped, with hundreds of men and boys labouring under the eyes of their white overseers.

So striking was the lack of machinery that Kipling was moved to ask his tour guide: ‘But has nobody found out any patent way of making these [opium] cakes and putting skins on them by machinery?’ No, came the answer; the making of opium cakes required skilled human hands, for the finished product had to be so perfect that ‘all the Celestials of the Middle Kingdom shall not be able to disprove that it weighs two seers one and three-quarter chittacks…’

The irony is that Sherwill, an aspiring scientist working with tools of representation that were intended to produce objective depictions, ended up creating images that were not just ideological but fantastically so. Through his visual language, he turned a grimy reality into a temple of Progress—a vengeful deity, who had to be appeased with sacrifices that involved the infliction of suffering on the benighted and the recalcitrant. And since the British Empire was the Church Militant of the cult of Progress, exacting these sacrifices from the colonized was considered inevitable, indeed a historical necessity. It is in this sense that the opium trade was also seen as a necessary evil in that it provided the British Empire with the funds that it needed in order to go about the business of converting its subject peoples to the worship of Progress.

Excerpted with permission from Amitav Ghosh’s Smoke and Ashes: A Writer’s Journey through Opium’s Hidden Histories published by HarperCollins

Smoke and Ashes: A Writer’s Journey through Opium’s Hidden Histories

Amitav Ghosh

HarperCollins

Pp 408, Rs 699