Shakuntala and Dushyant are staring into each other’s eyes, oblivious of their beautiful surroundings. In the backwoods, a deer emerges from the green thickness, but Dushyant’s gaze remains fixed as bare-bosomed Shakuntala stands adorned in flowers. “Hey exquisite woman of beautiful thighs, please accept me as your husband in a private wedding ceremony,” remarks Dushyant, troubled with love and lust.

Scenes from the Mahabharata come to life in Kolkata-based artist Shuvaprasanna’s paintings in oil and acrylic on canvas, as they celebrate both humanity and mystique of the great Indian epic. His collection The Mystique of the Epic, which was on display at Gallerie Nvya in New Delhi recently, evokes a sense of awe in the viewer.

Centuries ago, classical Sanskrit author Kalidasa, too, had chosen to narrate Dushyant-Shakuntala’s love story from the Mahabharata in his own words with erotic undertones, making it one of the greatest works of Indian literature.

More than a millennium later, Rabindranath Tagore’s dance drama Chitrangada, based on one of Arjun’s wives and the princess of the kingdom of Manipur, according to the Mahabharata, remains one of his significant works in which he explores the nuances of a relationship.

Mahabharata and Ramayana—two of the country’s greatest epics— continue to witness retelling with artistic bents from time to time. The examination and analysis of these narrations in contemporary times only deepens according to gendered, social and economic lenses.

Indian painter and author Bulbul Sharma, who wrote The Ramayana for Children, says that age-old stories from mythology hold a fascination for most writers not just in India but all over the world. “I have always been drawn to stories from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. In my book, The Ramayana for Children, I highlighted the natural wonders described by Valmiki and in my recent book, Fantastic Creatures in Mythology, I searched for unique beasts and beings from the epics. Indian mythology is so rich that we writers can never stop reaching into its vast ocean of stories,” she says.

One of the contemporary artistes who have flipped pages of mythology to create art, Shuvaprasanna says, “For eons, numerous creative minds, researchers, and scholars have kept themselves busy in the study of the mystique of this epic (Mahabharata). From Kalidasa to Satyajit Ray, Rabindranath Tagore to renowned filmmaker Peter Brook, generations of artistes have been influenced by the stories, and presented interpretations in their own works. The Mahabharata and the Ramayana continue to remain relevant into the modern day. These epics guide us to the right way of life in a certain way. There’s so much substance in Mahabharata that any creative person could create something from his/her perspective using his own wisdom, sensibilities and by reinterpreting its essence.”

Similarly, when Mysore’s Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV commissioned nine works for his Jaganmohan Palace to be rendered by one of the greatest painters in Indian art, Raja Ravi Varma, they were heavily inspired from the instances of Ramayana—‘Rama breaking the sacred bow of Siva before his marriage to Sita’, ‘Indrajit presenting to his father Ravana the trophies of his conquest of Swarga’ and so on. The Pahari paintings, by painters from mountainous regions in India, too, find their inspiration from both the Mahabharata and Ramayana.

Why epics must be retold

According to Neera Misra, historian and author of Connecting with the Mahabharata, ancient legacies of the two epics intrigue us because they narrate tales of people—from struggles of ordinary to that of the ruling classes, of women especially. In her book, she highlights the widespread geography and history embedded in Mahabharata. She says that she wrote as the locations where certain historical events happened still exist today and she has tried to present evidence-based depiction to address misperceptions about tangible and intangible heritage.

Several retellings being written, images from the epics being painted or performed with contemporary strokes reaffirm the fact that there are endless lessons to be learnt from our epics and every creative mind has its bit to offer.

In print, authors Amish Tripathi, Devdutt Pattanaik, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni and P Lalita Kumari (who goes by the pen name Volga) have selected, dissected, and re-written bits and pieces of epics in their own voices.

In fact, both Amish Tripathi and Devdutt Pattanaik have extensively churned out stories and written a book each on Ram, Sita and Ravan. While Pattanaik has written his version of Hanuman Chalisa, Shikhandi, Gita, and Mahabharata, Tripathi—who is bringing out the Ram Chandra series—has released his War of Lanka, Suheldev and Shiva Trilogy, among others.

Another weaver of the myth, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Forest of Enchantments brilliantly places Sita at the centre of the story while also humanising other women and questioning women’s autonomy in the world of privileged and patriarchal men. In her The Palace of Illusions, Divakaruni sets out to reimagine Mahabharata from a woman’s point of view, through the voice of Panchali (Draupadi).

Divakaruni feels that the lessons our epics impart are evergreen and hence, it is important to retell the stories in different ways, through different mediums. “In different ages, readers or viewers will find a particular lens more relatable. It might help them understand their own challenges. Thousands of readers have written to me, over the years, that seeing the Mahabharata through Draupadi’s eyes and viewing how she battled against great odds gave them a great deal of strength to meet the challenges they faced in their own lives. For this reason, I encourage responsible re-tellings of our epics, puranas and other ancient tales, and I hope to dive back into them again,” she says.

Also Read: Diwali and diamonds: Festive and wedding season fueling the diamond jewellery market

Mythological retellings often find an upper hand in the children’s genre as the complicated texts are re-written for the young minds often to inculcate lessons and values from the epics.

“Parents are eager for their youngsters to be exposed to these stories that are rooted in Indian culture and mythology—tales of mighty heroes/ heroines and their heroic deeds, tales that give a context to how we view the world around us, tales that make us examine our actions and prepare for outcomes,” says Sohini Mitra, publisher, Penguin Children’s Division.

“Retellings and newer formats or editions allow for a more contemporary way to present these to a new-age audience, breaking stereotypes and unilateral narratives,” she adds. Mitra cites examples of Devdutt Pattanaik’s retellings—The Girl Who Chose: A New Way of Narrating the Ramayana and The Boys Who Fought: The Mahabharata for Children—to suggest how the stories have been reframed, giving agency to Sita and the Pandavas, while introducing concepts like empowerment, duty and ‘choice’ for the younger generation to read and ponder over.

Shuvaprasanna adds that the retellings of any epic becomes popular as people constantly look for different interpretations that resonate with everyday life rhythm and are relevant to their times. As a result, every time an epic is retold with contemporary or personal renditions, it gives a new form and essence to the story.

Retellings must also be written to contemporise ancient tales with modern sensibilities. Koral Dasgupta, author of The Sati series—a five-part series on Draupadi, Kunti, Ahalya, Mandodari and Tara—says that Indian epics constantly challenge each generation to excavate a hidden treasure cove. “Ramayana and Mahabharata were not written for mere entertainment; they were meant for philosophical and spiritual consumption. As time passed, people could not keep in touch with the philosophy and considered only the skeletal stories. They sounded regressive, feeding a patriarchal system well,” she says.

Dasgupta, whose third book Draupadi released in September, says that when she heard Sita’s story, she understood that women’s foolishness caused great wars. “Draupadi’s story told me that women are dependent on men in winning their battles. I grew up thinking that my religion and culture prefer timid, obedient and sacrificing women. Much later, I realised that the stories were told to me in a way that restricts my dreams and freedom as a human being,” she adds.

“Very few people understand that Draupadi was a homemaker extraordinaire, her hospitality was famous. The magical palace of Indraprastha was reflective of Draupadi’s success as a queen and a mother—she was affectionate and entertaining. The public memory has lost this identity of Draupadi and remembers her as a ‘victim’ of molestation whose anger led to a great war and killed people. My book unravels various aspects from her life, some events occurred before she was born—which slowly built up the inevitable war situation,” Dasgupta further says.

Not just in different mediums, Indian epics also find varying accounts of events in their different versions. The national epic of Laos, Phra Lak Phra Ram, was adapted from the Ramayana; Reamker is the Cambodian epic poem based on the Ramayana; Ramakien is Thailand’s national epic that owes its roots to Valmiki’s Ramayana, Kamba Ramayanam (also called Ramavataram) is the Tamil version of the epic that was written by Tamil poet Kambar in the 12th century. Bhanubhakta Ramayana is the first Nepali epic; Saptakanda Ramayana is the Assamese version of the Ramayana; and Sri Ranganatha Ramayanamu is the Telugu adaptation of Valmiki’s Ramayana.

According to Tarini Uppal, commissioning editor, Penguin Press, Penguin Random House India, epics were traditionally passed down through the oral tradition and that meant several versions of it existed. “The same stories were told from one generation to the next over thousands of years in different parts of the subcontinent. The universality of the lessons and wisdom in these texts will hold true in every new retelling to come,” she says.

Deepthi Talwar, executive editor, Ebury Publishing and Vintage, Penguin Random House India, seconds Uppal. “The stories within the epics, and the characters portrayed in them, are so rich and nuanced, it offers up the possibility for different retellings—there’s scope for writers to reframe them and retell them with a new perspective,” she adds.

Flying arrows & cult shows

Ramanand Sagar’s 1987 cult show Ramayan was probably one of the first prominent screen exposure to the epic. Actors Arun Govil and Dipika Chikhlia began to be worshipped as real-life gods, thanks to the popularity of the show, and Dara Singh went on to play numerous roles as Hanuman. With basic technology and a simple storyline at work, the show managed to become a classic and, so far, remains the most popular rendition on TV. With no VFX at play, the shot of arrows was unusually slowly delivered to the target and Lord Hanuman almost flew in slow motion. But when Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan and BR Chopra’s Mahabharat returned to screens during the pandemic, their popularity outdid that of any modern renditions on TV. Nostalgic families watched the episodes like it was the 80s with a slowed down pace of life and a minimalistic lifestyle.

Author, columnist, screenwriter and public speaker Anand Neelakantan, who wrote the prequel books for Baahubali, and several others such as Ramayana Asura: Tale of the Vanquished based on the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, shares that Indian epics are so ingrained in our culture, thinking and civilisation that there is no escaping them even if a writer wants to. “As someone who grew up with retellings and counter-tellings, it was a natural choice for me when I decided to write. While I was writing Vanara from Bali’s perspective as a novel, I was writing Mahabali Hanuman in which Bali is a villain for television. I wrote Asura from Ravana’s point of view while my popular TV series Siya Ke Ram was from Sita’s perspective. While I was writing The Very, Extremely, Most Naughty Asura Tales for Kids, I found that our epics can be so entertaining for children too. No other ancient literature, scripture or religion allows so much flexibility,” he adds.

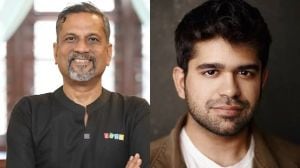

From popular 2015 show Siya ke Ram that retold Ramayana from Sita’s eyes to announcement of the upcoming Mahabharata being helmed by producer Madhu Mantena’s production house Mythoverse Studios, from Akshay Kumar’s Ram Setu that releases on Diwali to Prabhas- and Kriti Sanon-starrer Adipurush that releases in January 2023, makers of shows and films constantly find fodder from epics. The fact that there are several shows and films retelling the same story, does not stop new shows and films from emerging. Mantena’s show will be aired on Disney+ Hotstar and is being said to be the grandest version of Mahabharata on screen so far.

However, that has not stopped makers from recreating the epics on screen. Another film is in the developmental phase as filmmaker Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra and Anand Neelakantan are co-writing mythological drama film Karna, which will likely be a two-part film.

Mantena says that for centuries Indian epics have captured the imagination of billions around the world. “These epics are deeply woven into the very fabric of our nation. The Mahabharata, one of the oldest epics in India, despite being as old as time, is still relevant today for the many lessons and words of wisdom hidden within its ancient verses. It is said that every known emotional conflict experienced by mankind finds form in Mahabharata through its complex characters and storylines,” he adds.

Though it would be inadequate to compare Ramlila to a television show based on the Ramayana, both remain to be retellings of the epic. The annual folk re-enactment of the epic draws crowds in thousands even though it is staged every year during the days leading up to Diwali.

As the crowd comes back on the grounds to watch a physical Ramlila after the pandemic, the excitement and the scale of the shows are touching new heights. From performances in local playgrounds to classic shows that have earned a reputation over the years, every locale has a Ramlila arrangement that retells the story of Ramayana in its own unique way.

Shri Ram by Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra is a must-watch on Delhi’s annual cultural calendar. The dance drama has remained true to its spirit since its inception and enjoys an undying popularity. Shobha Deepak Singh, director and vice chairperson, Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra, says that the primary goal is to educate both the younger generation and adults about how Shri Ram represented ideals. “There are numerous concepts that are difficult for the average person to comprehend. It is for this very purpose that every year, we take on the task of performing it for more than three weeks. It is absolutely essential for the Kendra to retell Ramayana in different mediums because the scenes in Ramayana vary so much from each other,” she says.

Broadway Ramlila by Aryan Heritage Foundation in Delhi narrates the saga of Ramayana in a grand and spectacular way, weaving the entire story, from Lord Ram’s birth to his eventful coronation, into a capsule of three hours. The show is equipped with modern technology in terms of music, sound, choreography, lighting, stage design and costumes.

Likewise, Ramlilas across India don’t only differ in presentation and scale but also vary from state to state. In Varanasi, Ramnagar’s Ramlila is a famous event. In Lucknow, the Aishbagh that was built by Asaf-Ud-Dowlah, is a popular spot for the celebration of Ramlila. Prime Minister Narendra Modi too visited the Aishbagh grounds during Dussehra in 2016. The performances are helmed by Shri Ramlila Samiti. With Ayodhya becoming a prime tourist spot with the construction of Ram Mandir, Ayodhya ki Ram Leela is also expected to be a star-studded event with many politicians in attendance.

With the governmental push towards promoting religious tourism and strengthening Ramayana trails in India especially at Ayodhya and both the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata proving to be constant sources of information for newer works or retellings through different mediums, the conversations around the epics are only expected to grow.