By Shubhangi Shah

‘Who am I?’ This can be a loaded question for anyone, and not just a Bhangra-loving son of an English mother and Indian father in the UK having perfect command over Punjabi with Jassa Ahluwalia as his name.

As a teen, Jasvinder Singh Ahluwalia is reprimanded by his South Asian teacher “for doing an Indian accent”. “Why had my Gujarati friend been spared this lecture?” he reflects. Several years later, writhing with pain at a London hospital, he is unable to explain his mixed heritage to the staff that is unable to match his name with his looks. So he decides to take matters into his own hands, and Jasvinder becomes Jassa. “What I was henceforth assuming, adopting and determining to take and use was ambiguity,” Ahluwalia writes.

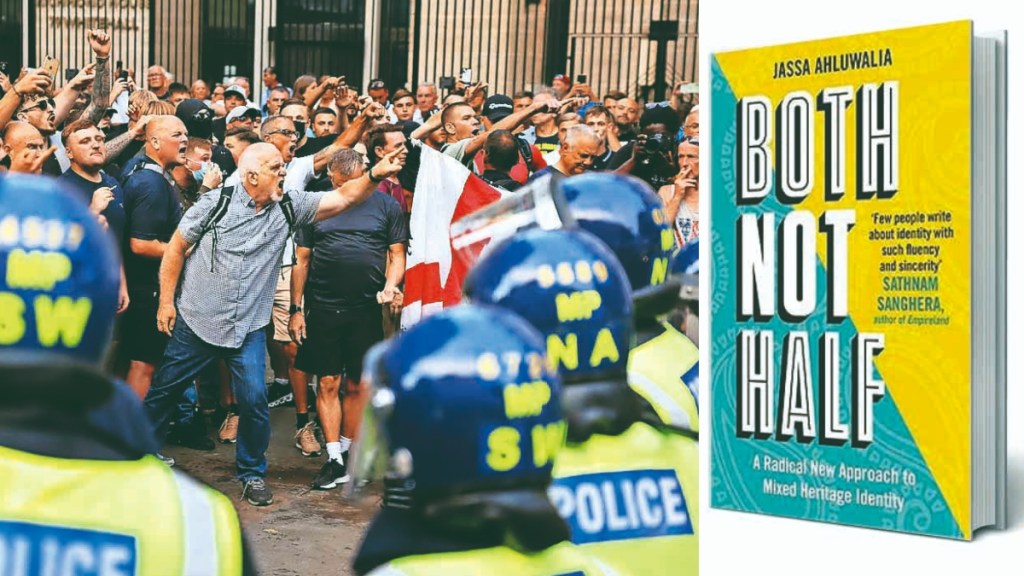

Both Not Half: A Radical New Approach to Mixed Heritage Identity is a poignant and rational read, and Ahluwalia’s deep and often bold dive in search of his identity, an identity where his British and Indian heritage don’t exist in halves but as a whole, one not overpowering the other, but co-existing in tandem.

And this search takes him to places, from the alleys of history—William Dalrymple’s White Mughals and India’s British past that birthed the Anglo-Indians—to fictional characters, from The Jungle Book’s Mowgli to Kim, another character by Rudyard Kipling of an Irish orphan in Lahore who is in search of his place in this world.

Kipling, the India-born British novelist, features prominently in Ahluwalia’s search for his identity, whether through the beloved character Mowgli—“He was a young boy, caught between two worlds, searching for belonging. This was me. This was my story”—or through the character’s creator himself. “India and his childhood were a lost paradise into which he could escape,” he writes about Kipling.

However, here Ahluwalia is careful as he tries to piece together his identity through Kipling and his fictional characters, while not forgetting the man’s ideology in the process. “This was the man who coined the term ‘white man’s burden’, a writer who ‘has been variously labelled a colonialist, a jingoist, a racist, an anti-Semite, a misogynist (and) a right-wing imperialist warmonger,” he highlights.

Such focused awareness runs through the book, which beautifully brings diverse themes together, with Ahluwalia’s quest for his own self running as the binding thread. “I’m sure my whiteness insulated me,” he writes, while also bringing forth the lived experiences of his brown father in a country that is increasingly showing its outlook on immigrants of colour.

Here, Ahluwalia specifically writes of an incident of his parents attending a wedding: “They were in the reception line to congratulate the newlyweds; my mom had just given the groom a hug and my dad followed, holding his hand out for a handshake. The groom kept his hands by his side. My dad kept his hand out. The moment became an eternity.”

In a gross realisation, where Ahluwalia reflects upon how his dad had to point out that he was, in fact, his son, often without being asked, so as not to be mistaken for his lover, he writes, “Our collective ignorance has made families like mine and Alisha’s seem so anomalous that we are assumed to be our parents’ lovers before we are recognised as their children.”

While the first half is more personal, in the latter part of the book, Ahluwalia expands his view and undertakes a scrutiny of society and what it means to be British.

“Britain is encumbered by a medieval attitude, emboldened by memories of imperial dominance that manifests in our present with a ‘don’t like it, there’s the door mentality,” he writes.

This runs deep especially with the ongoing anti-immigration protests, the worst rioting that the UK has witnessed in 13 years.

“Modern Britain was largely built with the wealth extracted from undivided India, creating the economic conditions that led to so many who belong to these religious groups migrating to the UK,” Ahluwalia writes.

Whether it’s a telling of his personal experiences or a commentary on society and politics, the research, whether it’s reading books or talking to people, clearly shows. And as Ahluwalia switches from personal to political, which he does often, what keeps the reading light and breezy is the language, which is simple, devoid of jargon, and effective.

Consider this: on choosing Russian as a language in college, he writes: “The alphabet looked pretty badass.” Or when reprimanded by his teacher over doing an Indian accent, he reflects: “But I was a teenager. Everything made me feel weird, humiliated and angry.” Throwing Punjabi words here and there, words like pind, muth maar, and matha tek, too, works beautifully, where the language works perfectly in tandem with the theme.

Ahluwalia’s Both Not Half is a personal yet universal take not only on his mixed heritage identity but on an inclusive world as well, where people of different identities—racial, religious, or gender— live in perfect tandem, a world we all need, and can benefit from.

The authors is a freelancer.