By Reena Singh

The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, was implemented with the purpose of conserving the country’s wildlife and to restrict hunting, smuggling, and illicit trading in wild animals and their derivatives. But after the liberalisation of the Indian economy in 1991, the promotion of wildlife conservation took a dip, and the management of these institutes grew worse with every passing year. Considering the rising frequency of wildlife crimes and the growing alienation of local populations with wildlife conservation, the Wild Life (Protection) Act (WLPA) was amended to facilitate the protection of flora and fauna. “It is a book of short stories with a difference,” believes Manoj Kumar Misra, a former member of the Indian Forest Service, as he commemorates the five decades of India’s wildlife journey in short personal anecdotes by pioneers who have worked for wildlife conservation. These are 30 ‘lived’ tales told by people from different spheres of wildlife research, reporting, volunteering, jurist, and include field practitioners and enthusiasts such as journalists, artists, advocates, and wildlife biologists.

Also Read: A chronicle of a sectoral journey to stardom

The first-person narrative takes the reader on a personal journey that enlightens them on the different shades of processes, organisations and experiments that have spawned over the years. The book is divided into two parts and offers an insight into varied aspects of wildlife conservation over the past decades and what could unfold in the future. The first part includes matters that are directly related to the WLPA, whereas the second focuses on the personal accounts linking to institutions, people, and projects.

The introduction of the Act infused new hope and enthusiasm in officials involved in wildlife conservation. But the protected areas and the wildlife they sustain have always faced multifaceted challenges, which are deep rooted in the complex sphere of the political economy of conservation. It calls for suitable actions built around the equitable distribution of resources, social justice, and respect for common citizens. The inclusion of local people in the wildlife management emphasises that people and parks need to be with each other and not opposed, so that the core functioning is strengthened, and various agencies work in an integrated environment.

The articles take us through the harrowing journey of the WLPA bill amendment and its aftermath, discussing the need to ensure that we adopt approaches that take us toward holistic ecosystem conservation. It talks about how wildlife tourism can not only bring significant funds to reserves, but also have a remarkable impact on raising awareness and appreciation of nature. Wildlife tourism needs to be a more interactive learning experience that can reduce rural poverty by enhancing livelihoods in the communities around the reserve. Manegaon represents an example of a community-led conservation effort. It has blackbucks that are only found in the village area around the Navegaon-Nagzira Tiger Reserve. For them it was not only the monetary gains from tourism that motivated them toward conservation, but also the village’s pride in a wildlife species.

Also Read: Book Review: Lion of Ladakh

Rapid urbanisation and the spread of cities into erstwhile wilderness areas is a readymade recipe for an increase in human-animal conflicts. Instances of wild elephants, sloth bears, leopards, gaurs and hyenas entering cities are being reported. Images of people chasing cruelty towards elephants, and death, depredation and property loss for humans evoke strong emotions. The villagers have been trained to use high beam torches, blinking lights, chilly smoke and loud noises to protect their crops and to drive elephants back into the forest areas. Though the elephant groups are regularly monitored, and anti-depredation squads equipped with vehicles and tools have been placed in the affected areas, these wildlife habitats and corridors for wildlife movement are protected with the prevention of rapid land-use changes.

Elephants, the Great Indian Bustard and Bengal florican have declined rapidly due to habitat mismanagement. Initiatives such as the Conservation Action Support Programme and Community Biodiversity Conservation Programme supported local community groups for the protection of biodiversity resources or securing community conserved areas. It led to several good projects getting developed and implemented in the field, with capacity-building and professional growth of the respective executants. Special training sessions on wildlife crime prevention and regular coordination meetings with the judiciary were held for forest staff of the park and the adjoining forest divisions around Panna tiger reserve.

From managing wildlife in captivity to the existential threat of animals and birds, this book covers every aspect of wildlife conservation. It also talks about the dire need of attention towards the marine ecosystems and the need to act towards the climate threat that hovers over our natural habitats and what the future upholds. Since this book adopts storytelling, it is not only for the niche audience of wildlife legislators but also for the laypersons who are interested in understanding India’s wildlife conservation journey through the eyes of those who have lived it.

Dr Reena Singh is senior fellow, ICRIER

(Views expressed are personal)

Wildlife India@50: Saving the Wild, Securing the Future

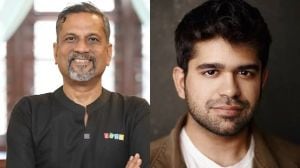

Edited by Manoj Kumar Misra

Rupa Publications

Pp 544, Rs 995