By Anay Shukla and Shriya Pandita

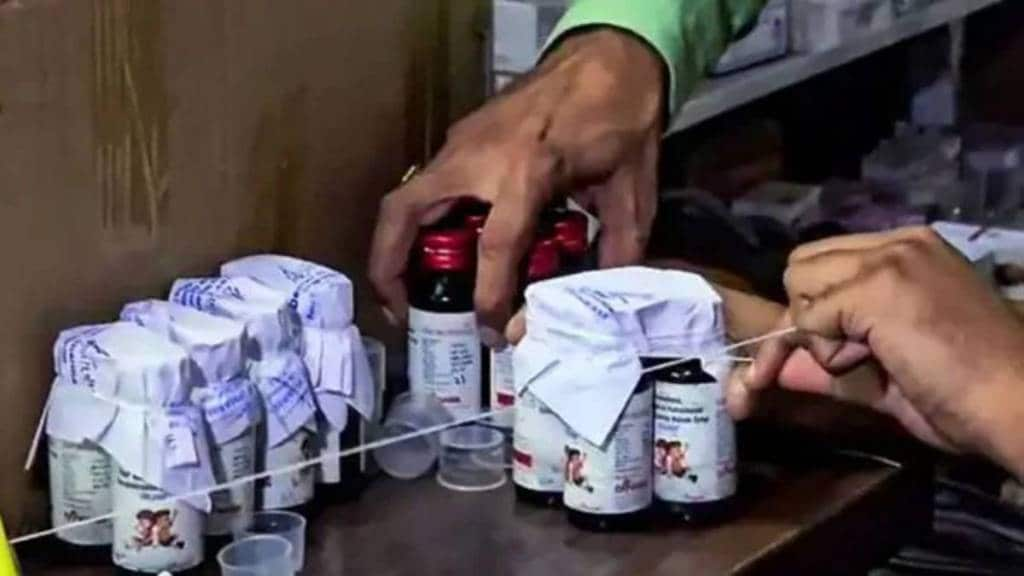

The recent deaths of children after consuming a cough syrup have once again raised fears of contaminated drugs. Lack of quality control in manufacturing facilities and delays in conveying adverse events need to be addressed strictly, explain Anay Shukla and Shriya Pandita.

What caused the death of 20 children in MP?

The probable cause of death of the 20 children in Madhya Pradesh appears to be kidney failure due to the consumption of cough syrup which contained a toxic chemical known as diethylene glycol (DEG). The exact cause of death is yet to be confirmed. The cough syrup consumed by the deceased children probably contained glycerin, which is a common ingredient used in cough syrups because it has soothing properties and also helps in thickening medicines. DEG mimics the properties of glycerin, and therefore to cut costs it is added to glycerin as an adulterant. However, unlike glycerin, which is generally regarded as safe, DEG is an industrial chemical with a history of being fatal to human beings when consumed. The applicable Indian standards permit up to 0.10% DEG in glycerin as impurity. However, according to new reports, batches of cough syrup consumed by the deceased children contained around 48% DEG impurity, which proved fatal when consumed.

How does it India’s image as the ‘pharmacy of the world’?

The fact that cough syrups can be easily contaminated by DEG has been known for many years, and India has faced embarrassment for exporting cough syrups containing DEG. Countries such as Uzbekistan, Gambia, and Indonesia have earlier called out Indian manufacturers of cough syrups for contamination with DEG. However, there is also evidence to suggest fake medicines claiming to be of Indian origin are sold in some of these countries. The risk of exporting DEG contaminated cough syrup was brought under control after intervention at the highest levels of government, particularly the central drug regulator and customs authorities. This was achieved by introducing mandatory testing before export. However, the recent deaths are a blow to India’s image as the “pharmacy of the world” as the manufacturer has been inspected by licensing authorities before granting a licence.

Govt response to the MP deaths

The state government took around 20 days to determine the exact cause of death, and attributed the delay to parents’ refusal to allow autopsies. To quell public outburst, a doctor who prescribed the syrup and a pharmacist who sold the medicine were arrested. The lab analysis of the confiscated syrup did not detect DEG. But when the state requested the Tamil Nadu (TN) government to test samples of cough syrup from the manufacturer’s location, DEG contamination in fatal quantities was discovered. MP, TN, and other state governments ordered to stop selling the contaminated batch. The TN government cancelled the manufacturer’s licence. States like Telangana tested other cough syrups, and ordered the supply chain to stop sale of sub-standard drugs besides issuing public advisories. The Centre does not oversee manufacturing. The central drugs regulator issued a circular urging state regulators to enforce legal provisions to prevent the manufacture of sub-standard medicines. The Centre also issued an advisory against giving cough syrup to very young children.

Reasons behind such incidents

There are two obvious reasons—lack of quality control at the manufacturer’s level and delay in conveying adverse events at healthcare facilities. Each manufacturer is required to test raw materials beforehand and all batches of medicines. In-house quality control experts mandated by law oversee testing, and the drugs cannot leave the factory without the sign-off of these experts. It is unlikely for DEG contamination to go undetected when raw materials are tested and later when batches are released. The state drug control departments are also responsible for routine inspections of manufacturing sites. There is also the lack of a robust and user-friendly reporting framework for serious, unexpected adverse events. The government could take steps to roll out such a comprehensive reporting system across hospitals, supply chain, and health and regulatory agencies. To their credit, the central and state governments are taking steps on this front, but in the context of the MP tragedy it is too little, too late.

How to prevent such episodes

The government plans to make improved standards of manufacturing practices (called revised good manufacturing practices) applicable for small and medium-scale medicine manufacturers from December. It should also make it mandatory for all manufacturers to get high-risk medicines like cough syrups tested at a third-party lab before release. This may have impact cost in the short term, but it would help restore public faith. In the long term, the authorities must ensure quality teams in manufacturing units are qualified and immune from commercial pressures. This will guarantee personal accountability. The state government should also ensure risk-based inspections are conducted more thoroughly and frequently. There has to be a system of accountability and enforceability that is not just on paper.

The authors are respectively founding partner and associate, Arogya Legal