By Sonal Desai

Early on in my career, I worked at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), where I cut my teeth on a wide range of emerging markets. At the time, the running joke among the fund’s economists was that “IMF” really stood for “It’s Mostly Fiscal,” because policy recommendations centered on the role of fiscal policy. The idea was that a prudent, sustainable fiscal stance underpins macroeconomic stability, whereas a persistently loose fiscal policy makes life a lot more difficult, especially for the central bank. The Federal Reserve (Fed) seems to be finding out how true that still is.

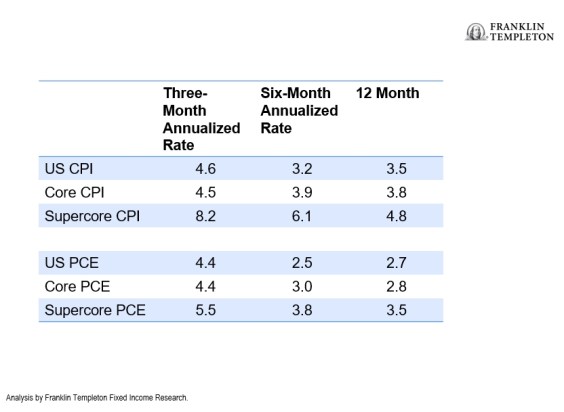

The Fed’s governors walked into the May policy meeting with three months of unpleasantly high inflation readings in their briefing material. At the previous meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell still held out hopes that the January and February numbers might be outliers; this time he conceded that it is hard to ignore a full quarter of persistent inflation pressures. To get a sense of just how robust inflation pressures remain, take a look at the following table:

Comparing the three-month annualized moving average to the six- and 12-month figures highlights a marked acceleration across all US inflation measures. Supercore Consumer Price Index (CPI, core services excluding housing) running at over 8% in the past three months is especially striking, but headline and core measures of both CPI and personal consumption expenditures (PCE) are hardly reassuring, powering ahead at an annualized average of 4.5%.

Asked about stagflation fears, Powell quipped that he could see neither the “stag” nor the “flation.” The numbers above suggest instead that you don’t have to squint too hard to see some good old ‘flation.

The ”stag” part remains the lesser concern, for now, even though last week’s US economic data saw some weaker-than-expected readings, with significant misses on both non-farm payrolls and the Institute of Supply Management Services Index. The US unemployment rate remains under 4%, however, confirming that the labor market remains relatively strong—still supporting a healthy rising pace for unit labor costs, which rose close to 5% in the first quarter of this year.

Against this background, the Fed’s press conference following the policy meeting was remarkably dovish. Powell is right to keep a close eye on any signs of weakening growth after 2023’s blistering performance, but persistent inflation remains the clear and present policy challenge.

Powell made it clear that he (and the Fed) would very much like to cut rates, but financial markets appear to have internalized the fact that the Fed cannot cut rates yet.

Powell painted different possible scenarios that would trigger the start of a rate-cutting cycle: an unexpected sharp weakening in the labor market, for example, or the Fed gaining sufficient confidence that inflation is heading to the 2% target in a sustainable way.

After the last three inflation readings, it would take several months of more encouraging price data for the Fed to get sufficient confidence—a renewed acceleration in inflation after rate cuts started could prove destabilizing for financial markets. Given the calendar of monetary policy meetings for the rest of the year, I continue to believe that this narrows the room for maneuver to two rate cuts at most this year.

On the back of the weakness in payrolls, the short end of the US Treasury yield curve rallied, but the long end showed a more moderate move, and is likely to remain much more sensitive to the fiscal picture and more cautious on inflation prospects.

Unable to cut interest rates just yet, the Fed decided to significantly slow the pace of quantitative tightening—it will now reduce the US Treasury portion of its balance sheet by only US$25 billion per month from an earlier US$60 billion.

Powell denied that this implies an easier policy, drawing what to me appears to be a specious distinction. He maintained that only interest rates are the true monetary policy instrument, whereas the balance sheet only aims at preventing dysfunctions in the running of financial markets. This is a somewhat disingenuous argument, in my view: Quantitative easing was deployed—and presented—as a monetary easing tool. It follows logically that slower tapering of the balance sheet implies an easier policy stance than was previously envisaged.

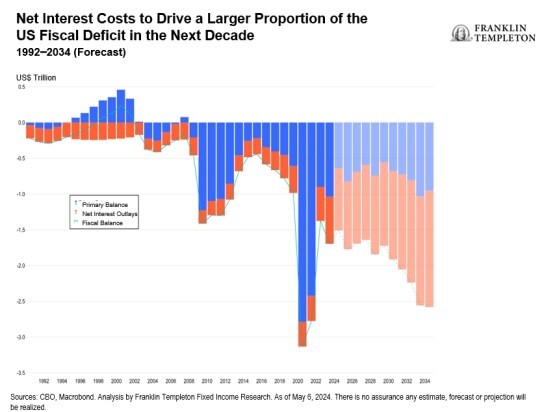

Here’s the rub: the Fed will be buying up between a quarter and a third of the bonds issued to finance a gargantuan fiscal deficit of around $US2 trillion. This brings me back to my original point: A persistently loose fiscal policy is already driving a surge in government interest expenditures—a classic case of fiscal dominance. This creates implicit pressure on the Fed to try and alleviate the pressure on government funding costs. With inflation still running too warm for comfort, this puts the Fed in a very tight spot, trying to ease monetary policy by stealth and taking some extra risk on the inflation front.

So far, market concerns about loose fiscal policy have been episodic. However, investors might eventually focus in a more sustained way on the issuance implications of massive fiscal deficits. If a cooling labor market led the Fed to cut interest rates, we might then witness a mirror image of former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan’s famous conundrum: long-end yields might remain stubbornly elevated in the face of falling policy rates, particularly if disinflation progress remains painfully slow.

(Author is CIO, Franklin Templeton, Fixed Income)