By Commander KP Sanjeev Kumar (Retd)

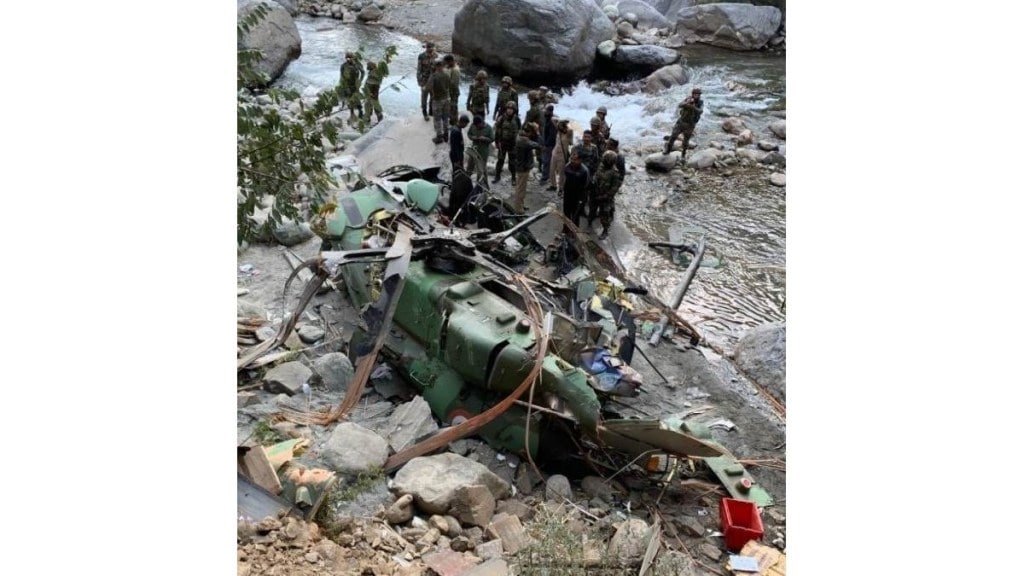

An Indian Army Advanced Light Helicopter (ALH) Mk IV “Rudra” that took off from Likabali morning of Oct 21, 2022 crashed at about 1043h IST in a hilly, forested area South of Tuting in Arunachal Pradesh. A joint air force-army search and rescue operation was immediately launched. The official Twitter handle of Indian Army’s Eastern Command confirmed my early fears on seeing an eyewitness video of smoke trail rising from the dense forests of Migging.

Two officers and three soldiers onboard the chopper are no more. Remember to send up prayers for families of the departed as you light your diyas this Diwali. Maj Vikas Bhambhu, Maj Mustafa Bohara, Cfn Aswin KV, Hav Biresh Sinha & Nk Rohitashva Kumar will never celebrate Diwali again. Army described their deaths as “supreme sacrifice“, just as it did for a fatal Cheetah crash a fortnight ago. A “supreme sacrifice” in peacetime with no contact with the enemy? What is that? What exactly snatched these young lives away?

Grim reminder

The latest crash is the third fatal accident of Army Aviation on ALH WSI Rudra since Jan 2021. Almost three years to the day, before another Diwali weekend like today, an ALH Mk 3 with the Northern Army Commander onboard crashed in the hills of Poonch on Oct 24, 2019. The helicopter was totalled while the occupants miraculously escaped with minor injuries.

Sadly, there are no survivors in Friday’s crash. We don’t know what happened in the latest case yet but visuals of the location indicate that safe recovery from any kind of catastrophic failure would have been severely hampered because of “hostile terrain” below. There are limits to what a pilot can do to save a doomed aircraft. The deceased pilot(s) reportedly punched out a Mayday call on the frequency in use — signifying “imminent danger” to the aircraft and its occupants. The crash recorders (CVFDR) will hold crucial evidence that the public at large will never know.

An information void that “sources” fill

As expected, conspiracy theories started floating around in social media. Disinformation and misinformation quickly occupies voids in credible information. In the absence of public briefings by official sources, speculation runs rife. In India, rather quickly, the limelight moves to a different tragedy or political circus and life goes on. This sadly has been the way of our people. No military aviation accident report in India is ever made public. This allows everyone except living pilots to get away. Dead crew in any case don’t matter in our scheme of things — least of all young officers and personnel below officer rank (PBOR) who, in the wake of any tragedy, as per the prevailing system, are either celebrated (gallantry awards) or consigned to the bin of history with the “he signed up for this” tag.

Purpose of this article

No data of any meaningful value related to flight safety and accident investigation is ever put out by the armed forces for public scrutiny in India. Hence, one cannot expect anyone outside the system to analyse or offer mitigating strategies. My attention was drawn to an article in The Print that made an oblique reference to the Oct 2019 army ALH crash. The story quoted “sources” that attributed the 2019 crash to “collective failure”. While deeply saddened by the latest crash, I write this article to clarify the practical and philosophical portents of “collective failure” to the layperson, now that the phrase is out in public domain. I have no intention to speculate on the latest crash that is the subject of an army CoI. Please bear me out with patience, objectivity and scientific temper.

How we “keep it all together”

The helicopter is kept in air by a spinning rotor that exhibits all the qualities of gyroscopic rigidity and precession, requiring a host of “cyclic” and “collective” pitch changes. Helicopter pilots control the rotor disc through the cyclic “stick” and collective “lever”. As helicopters grow in size and weight, “power-assisted” or “powered” controls become necessary if not “mandatory”. A helicopter in the ALH category (and above) requires hydraulic booster packs generating almost 180-200 Bar hydraulic pressure to move the rotor blades spinning well over 300 revolutions per minute. This is way outside human capability — you will likely break some joints before you can move the main rotor without hydraulics.

Hence two independent, redundant hydraulic systems are provided on such helicopters. The pilots operate the cockpit controls through “artificial feel”, “trimmers” and “spring feel mechanism” while hydraulic (servo) packs operating via flight control linkages and “booster rods” make the rotor do the heavy lifting. In a helicopter, failures in the flight control chain can be catastrophic; the weakest link in the chain will fail first.

On the ALH, for reasons unknown to the outside world, crucial parts in the flight control chain like “collective eye-end” and “booster rod” have failed in the past.

Catastrophic failures must be precluded by design

Major failures in a flight control chain will almost always be catastrophic. Certification thus requires such a high level of reliability and redundancy of hydraulics and the entire flight control chain as to preclude a major failure in the entire life of the fleet (in terms of flying hours you could multiply total number of airframes in the fleet multiplied by total technical life and raise it by a factor of “x”). Probabilistically, chances of failure in such flight-critical systems should be something like ’10 to the power minus 6′ — less than one in a million flight hours. However, even the best of systems fail. If the root cause is not established, or there is no drive to get to the bottom of things, expect FOLC — the meteorologist’s acronym for “further outlook little change”.

So if we have 3-4 occurences of “collective eye-end failure” or “booster rod failure” (maybe more; I don’t have that data, services do) over a pubescent 3.5 lac hours flown by the ALH fleet of 300+ helicopters, shouldn’t that raise a serious concern?

Understanding the “flying brick”

The Print article raises this important issue of “collective failure“. The collective lever in a helicopter is in essence the power lever. Moving the lever up or down controls the pitch of all rotor blades — collectively and by the same amount. Losing collective (or cyclic control) is worse than losing one or both engines. Let me explain why.

A helicopter is essentially a flying brick, kept in the air by spinning rotor blades that need cyclic and collective pitch changes for each and every condition of flight. The helicopter pilot’s last line of defence in an extreme situation of losing both engines (autorotation) is still way better than losing control over the rotor disc. A “collective failure” of main rotor essentially does that. It decouples the power lever (collective) from the main rotors, leaving the pilot to execute a “deadstick”, “cyclic-only” approach ending with a high-speed run-on landing.

“Collective failure” in a rigid rotor system

Unlike aeroplanes, helicopter landing gear (skid or wheel) is rather averse to high-speed run-on landings — about 40-60 knots (80-120 kmph) would be the outer edge of certified envelope on a firm, level, even surface; not to talk of water-landing where a running landing may “cartwheel” the machine over. Think of “control failure” as driving on a winding mountain road and suddenly losing the steering wheel. Wouldn’t properly certified automobiles absolutely preclude such an occurrence? Now think helicopters flying over treacherous, hostile terrain.

The ALH has a hingeless rotor system designed for high agility and performance stretching from sea level to super high altitude. It’s an elite club where only a few OEMs can safely compete. The one that keeps it all together in flight is the pilot, acting through the propulsion system (comprising engines and the rotor system) and the flight control chain. As opposed to helicopters with fully-articulated rotor systems that “feather”, “flap” and “drag” about mechanical hinges, rigid-rotor helicopters like ALH achieve all these three movements about elastomeric bearings and “virtual hinges”. The blades are forced to “twist and shout” through daunting aerodynamic odds by servo jacks holding the blades against flex-beam, elastomeric, not mechanical bearings. So, should any upper control linkages or primary servo jacks fail, the blades will almost instantaneously “offload” and spring back to ‘installed angle’ or one that offers least resistance to relative airflow.

What did we learn from 2019?

In short, should a “collective failure” occur, on the ALH, the pilot will be left with a high rate of descent, one-way-ticket-down, with an impending high-speed, cyclic-only landing. What if the terrain below is “hostile”?

It is for the reader to surmise the almost impossible odds that pilots flying Lt Gen Ranbir Singh & Co in the ALH Mk 3 on Oct 24, 2019 faced when they experienced “collective failure” in the most inauspicious location — hilly terrain with no clear area to carry out a running landing. In the event, the pilots skillfully managed to put down the helicopter in a valley within the maxim of “if you cannot save the airframe, save the pax”. Such feats are not repeatable or guaranteed for success each time; nor are such “failures” or “recovery procedures” standardised or described in OEM manuals — they cannot be; they are NOT supposed to fail.

Celebrate and move on? Or fix accountability?

But in our wicked scheme of things, the sentiment of “jaan bachi toh lakhon paye” (a life saved is worth millions) rules supreme. The army (hopefully) applauded and decorated the pilots who saved the day in 2019. But what lessons were learnt? What measures were taken to address this (recurrent) catastrophic failure? It is time to seek answers. The topmost echelons of services must answer. These losses are almost evenly distributed between IAF and Army in this case — yet another data point.

The services today are facing unprecedented challenges. Supply chains are strained due to ongoing conflicts. The faceoff at LAC has created significantly higher demand while indigenous capacities are still playing catch up under a climate of ‘import bans’. The top-down push for atma nirbharta that ignores safety and incentivises ‘fast track’ does little to help. Safe outcomes can only arise from greater accountability and deeper audits for design, quality and timelines. Sloganeering & posing before popping flash bulbs will only delay the inevitable deep dive for quality while mounting the body bag count.

We must move from the shambolic “something loose; something tightened” approach to create a more robust system of checks and balances where the trail of accountability is investigated to its root cause and fixed, wherever it may lead. It has become fashionable to celebrate the dead and fix the living after such accidents, most of whom are crew in their prime years. The relationship with other services and industry must be symbiotic — based on trust and accountability — not incestuous.

So, dear readers, whatever be the outcome of the latest ALH WSI Rudra crash, I personally view it as our “high-end”, “collective failure” to get to the bottom of things. Lives matter, not ranks. Jaan hai toh jahan hai. Drill deep & fix accountability. Chanting “Om Shanti” or “Rest in Peace” is just not enough.

Blue skies.

Author is former Test Pilot. This article has first appeared on his blog kaypius.com

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online.