Some prescriptions for the intended thrust on job creation by encouraging manufacturing seem to have an implicit underlying presumption of replicating?in varying degrees?the Chinese growth model. Even at the risk of caricaturing these prescriptions, the perception is that China managed its growth through a series of initiatives and policy measures over the last 3 decades, emphasising manufacturing and exports, which has transformed the role of manufacturing in its economy. As a corollary, an automatic presumption?validated by the China model of development?is that job creation will happen primarily in manufacturing. China?s GDP ($9.4 trillion in 2013) is now almost 5 times India?s ($1.9 trillion) over the span of 3 decades (their respective GDPs were about the same at $190 billion in 1980). While the actual dynamics underlying China?s remarkable, sustained growth are complex, a top-level, aggregated data review suggests that most of these hypotheses cannot be accepted and require refinement. (An independent paper published very recently by RBI details segment-level elasticities of employment.)

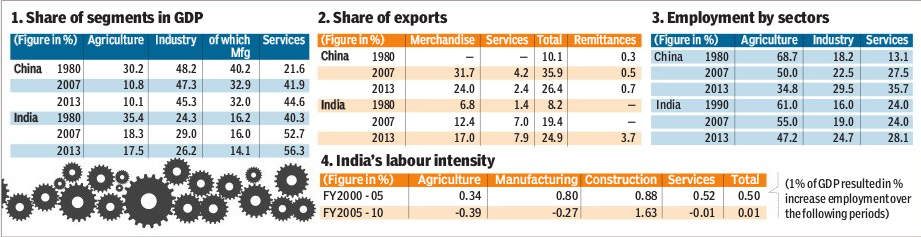

First, what has been the role of manufacturing in this transformation? The share of the industrial sector in China has risen from 44% in 1980 to 45% in 2013. In India, the corresponding share has inched up from 25% to 26%. No great shakes. It is the internals of industry that are even more fascinating. (A note of caution about the China?s data; although the broad magnitudes and trends are correct, there remains a degree of uncertainty about the exact numbers culled from different sources. However, this does not change the essential arguments of this article.)

Has manufacturing contributed the delta to China?s growth during the 3 decades? No. The share of manufacturing has actually fallen from 40% to 32%. Indeed, manufacturing does have a much larger role in China compared to India, but the share of manufacturing in China had always been higher than in India. In India, this share had been 17% which had fallen to 14%.

The construction segment has been one of the prime drivers of uncertainty in China?s national accounts data. To the best of our knowledge, there is no official estimate of construction sector data. We believe that construction is considered to be a part of China?s industry segment. It appears that construction has contributed more to India?s growth than it has to China. Its share has moved up from 4% to 7% in China and from 4% to 8% in India (remember that relative to a starting point, it is higher growth relative to the total which changes shares).

The transforming change in China has been the shift from agriculture to services. From 30%, the share has dropped to 10% over 3 decades, while in India this drop has been from 34% to 18%. The corresponding increase in the share of services in China has been from 22% to 45%, while in India this has moved up from 40% to 56%.

In other words, China?s growth cannot automatically be attributed to manufacturing, but is a far more complex phenomenon. China started with a manufacturing sector that was much larger than India?s and the share of manufacturing has been far sharper than in India.

The next hypothesis is that China?s growth has been export-driven. Table 2 shows that China?s exports grew from 10% in 1980 (the split between merchandise and services is not available, but presumably the share of services in exports then was small to negligible) to 26%. For India, this share has increased from 6% (4% merchandise and 2% services) to 24%. While nominally, this is a better showing for India, the share of services has increased even faster (from 2% to 8%). Of course, the share of merchandise exports has increased more in China than India, confirming all our perceptual impressions of China?s manufactures, and probably reflecting a conscious policy decision. It is also true that India?s GDP (and probably exports) is more import-intensive than China?s, reflecting lower indigenisation. Nevertheless, the bottom line is that China?s export intensity (as a share of GDP) is quite similar to India?s and hence not qualitatively significantly different as a driver of headline GDP growth, although the effects on the qualitative aspects are likely to have been significant.

The third aspect is the creation of jobs in tandem with growth. Of course, causation is likely to run both ways, each reinforcing and being influenced by the other. This is actually the crux of this article and deserves a more detailed treatment. We will address this in a separate companion piece. Table 3 shows that China has been more successful in transferring jobs from agriculture to other sectors, particularly services. However, India has not done significantly worse in industry, with an employment share of 25% (compared to 30% in China). But the story of productivity increases in growth is far more important and needs to be understood in greater detail.

Finally, going forward, the implications of the above for job creation in India need special attention. Table 4 shows ?Labour Intensity LI?, i.e. the increase in employment due to a 1% increase in GDP (ignoring issues of causality). In every sector but construction, the labour intensity during 2005-10 has worsened compared to the reference period of 2000-05 (these periods were chosen due to availability of large sample NSS surveys). Developing employment opportunities will not be easy. The silver lining in this is that a follow up large sample survey in 2012 (conducted to balance the distortions of the 2010 survey in the aftermath of the global financial crisis) indicates a marginal improvement over the 2010 survey, with the LI coefficient improving to 0.05 from the 0.01 in the table.

In summary, it might be facile to try and replicate the China model in India without a deeper understanding of the process underlying China?s transformation. Under-thought and ill-researched policies advocating measures are likely to result in outcome disappointment. It may well be that promoting manufacturing is key for jobs, it is just that the causation is not very obvious.

Assisted by Abhaysingh Chavan of Axis Bank

The author is senior vice-president and chief economist, Axis Bank.

Views are personal