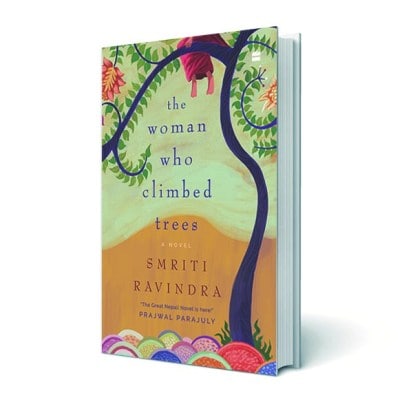

The Woman Who Climbed Trees: A Novel

Smriti Ravindra

HarperCollins

Pp 432, Rs 599

“I grew up being asked where I was from—‘Are you a Nepali or an Indian?’,” says Smriti Ravindra. “I am a Madhesi, and so much of my life has been impacted by this fact. There is very little to no fiction written on it. More than anything else, I wanted to write about the Madhesi experience in Nepal,” says the author, whose debut novel The Woman Who Climbed Trees recently won the Tata Literature Live! First Book Award—Fiction.

Here, Ravindra writes extensively on the idea of home. Married off at the young age of 14 to a Madhesi, the book’s central character, Meena, migrates to Nepal and, hence, loses her idea of home. It causes a double assault on her, as she is not only uprooted from the place and country she has known as home but is also separated from people she has associated as family and friends her whole life. This is what patriarchy does to women.

Patriarchy, too, is a pivotal element, which Ravindra brings forth through husbands who are largely absent, emotionally and at times physically, yet occupy a dominant position in the women’s lives and their households. There is so much more in this book. So we sat down with Ravindra to learn more about the different elements of her novel. Edited excerpts:

The book is largely set in Kathmandu and speaks of the lives of the Madhesis. Why did you choose to write on this subject?

More than anything else, I wanted to write about the Madhesi experience in Nepal. I am a Madhesi, and so much of my life has been impacted by this fact. Because of the rampant discrimination we faced from the Pahadis, my parents sent me and my three siblings to India for education. My mother spoke Nepali with a Maithili accent. She struggled with making friends and was lonely in a bustling city. Hence, home for me and many of my family members is a word fraught with conflict. And if I was to write with any authenticity, I had to set the novel in the breathtaking yet paralysing and ostracising lanes of Madhesi Kathmandu. I am, of course, writing about Kathmandu, which existed 30-40 years ago. It’s not the same anymore, nor is the city.

It is said that the debut novel of any author is an autobiography of sorts. How true is it in your case?

The novel is largely an account of what I saw and knew while I was growing up. So, yes, it is an autobiography of sorts. In fact, I began this novel as a journal the year my mother died. This was an attempt to have a conversation with her and hold on to her, whose death sucked the breath out of me.

However, as I wrote, I realised I couldn’t hold on to her by only focusing on what I had lived immediately with her. Rather, I had to ponder upon who she had been before I came along, who she was without me, outside of me. And as I wrote, I think I began to understand her, myself, myself with her, and so much more.

The book’s central character, Meena, is named after her. In fact, in a way, every woman in the novel is my mother. The hardened Sawari Devi, the irreverent Kaveri, the beautiful Meena, the irrationally angry Kamala Devi, the angst-ridden Preeti—these are all my attempts to understand my mother.

You write much about the relationships women in the novel had with one another. In fact, you dive deep into each of their lives, bringing about reasons they act the way they do. How difficult was this process?

A friend of mine teases me saying I love women who have passion. I laugh at her on this, but she might be right. I do love women. I am fascinated by the lot of us. I am fascinated by how we dress, eat, live, speak, surrender, resist, tell ourselves, or keep our silences. It was not that difficult to write about women. They were the reason I was writing in the first place.

The absence of husbands, emotionally and physically, is a crucial theme. Was it a conscious decision to write on this, or something that came about in the end?

It just came up. I did not intend to write it this way. But I suppose I have seen enough families with absent husbands and fathers. The ability to remain absent and yet be central to their households is one of the many powers that patriarchy has given men. In a particular section in the novel, I write about Bilash, the husband and father who is rarely home but whose likes and dislikes, needs, and comforts govern the lives of the women who live under his roof. His choice of food is cooked in the kitchens, his books are placed on the shelves. Many men are not around when their children are born, yet they control their children’s destinies. I did not set out to put this down. I set out to tell women’s stories, and as I told them, the men in their lives took on absent yet dominant shapes.

You also bring forth the madwoman element, a trope written and rewritten. What are your thoughts on that?

I actually feel it’s not portrayed extensively enough. I know so many unhappy women whose unhappiness borders on depression, whose unacknowledged depression renders them incapable of making decisions to live full lives. I know women who don’t know they are unhappy, but 15 minutes with them and you can sense their half-lives.

It is easy to simply call a woman erratic, or irrational, or overly emotional, to shrug her off as mysterious and confusing. It is easier to do this than to acknowledge the brutal and sometimes toxic environments in which many women live.

Men, who have not historically been expected to uproot themselves from everything that is familiar to them, who have not left their homes, languages, names, likes, and dislikes to follow a woman into an unfamiliar setting, don’t always understand how difficult and scary this culturally forced migration upon women is. We have glorified this migration through traditions and rituals, through our songs and movies, through the family structure, through the metanarrative of the daughter who is paraya dhan, but this glorification is a poor substitute for the mental agony so many women live through, often without knowing, and feeling guilty for the way they feel.

You also write about homosexual relationships and homoeroticism. Why was it important to bring out this element?

In a culture that is as restrictive as ours is, that has as many dos and don’ts as ours does, that is as afraid of individual choice, romance and sex, that forces young women into arranged marriages and allows them no space to discover their own tastes and desires, in such a culture, in such a situation, women often find their own safe spaces to explore their pleasures in and to quench their curiosities. My women are young and sexually ready, but have little to no outlet for the companionship and pleasure they crave. They express their sexuality in subversive ways, often under covers with people who will not disclose it, and practise it silently with friends, trusted sisters and relatives.

We are terrified of female sexuality and restrict it with all the might we can. A restrictive culture gives birth to deeply lonely women who are seeking connections and wondering how pleasure feels. And sometimes only a woman can identify with this search and engage in its give and take.

Lastly, the language you have written in is the one we generally use while speaking, with a prominent use of vernacular words. Any reasons behind it?

One of my biggest regrets is that I cannot write with any fluency in Nepali, Maithili or Hindi, though I am surrounded by these languages. And so, while I wrote in English, I also tried to minimise the distance between my Maithili-speaking characters written out in English. The only way I knew how to do this was by bringing in the vernacular and by borrowing the music of the missing language.