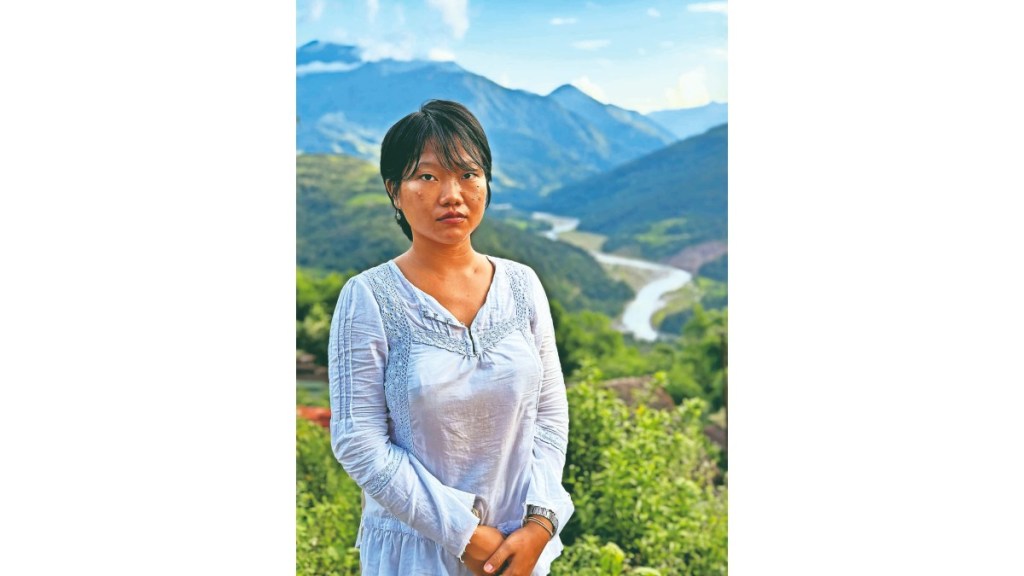

When Bhanu Tatak, an Adi woman from Arunachal Pradesh’s Siang district, first came to Delhi, she didn’t know she was about to step into the world of activism that would go on to define the next decade of her life.

Now in her late 20s, Tatak lives in Dibang and is an active leader of the anti-dam movement, Dibang Resistance. In 2023, she was awarded the Bhagirath Prayas Samman for her work in the space of river conservation.

Tatak tells FE, “My advocacy currently focuses on the impact of building dams in the Lower Dibang Valley. We are looking into the 2,880-MW Dibang Multipurpose Project and working on the downstream impact it will have in the Dibang Valley because there has been no cumulative impact assessment done so far on the effects of building a series of dams on a single river.”

Over the years, her work has shown promise on the ground too. A legal advisor for her hometown’s Siang Indigenous Farmers’ Forum, Tatak is among the third generation of people who have been protesting against dams in the region for the past 50 years. At the moment, she’s also leading a campaign against the 12,500-MW hydropower Siang Upper Multipurpose Project. “We are currently fighting four cases. The Gauhati High Court had said in one of our cases that the security and consent of the people is important before building a dam; and then it cancelled 44 proposed dams on the Siang river,” she says.

Tatak was also one of the people who led the campaign against the 3,097-MW hydropower project proposed on the Dibang river basin—the Etalin Project. Post their protests, the Union ministry of environment and forests cancelled the project for non-compliance with forest clearance regulations. Their fight still continues as another project has been proposed on the same river.

Tatak’s journey of activism started in Delhi University’s Miranda House. She was part of multiple fellowships and research projects surrounding caste discrimination. She says, “I was trying to understand the political question of caste and also understand about my own identity and how it’s placed in the mainland. For this, I decided to go to ground zero. I lived with people from the Mali caste in a village in Rajasthan for three months, and then I also lived in a village in Uttarakhand for a month.”

That was where she learned about the power of public participation in governance, and how to organise campaigns and mobilise people. In 2020, she started volunteering online with the Dibang Resistance movement that was slowly originating back home. “I was the only one from my village who had experience in advocacy work, so I had to take up the responsibility to speak up about our ecology.”

Two years later, in 2022, her life changed. As part of a protest called ‘No more dams’, two of her friends got arrested for allegedly defacing a mural on the boundary wall of the state civil secretariat in Itanagar. Tatak was named in the chargesheet as the main instigator. She had to leave behind her life in Delhi and move back home. “If the land is gone—which will be submerged if the dam is built—the ancestral land of whole tribes will be gone, our culture and our roots will be gone. It’s an existential crisis for us. We have to protect our home,” she adds.