“I found it hard to get over my broken heart, I thought I never would. Then one night, by the moonlit river, something happened that changed everything”

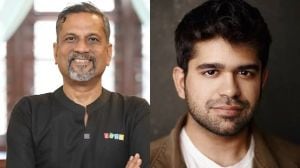

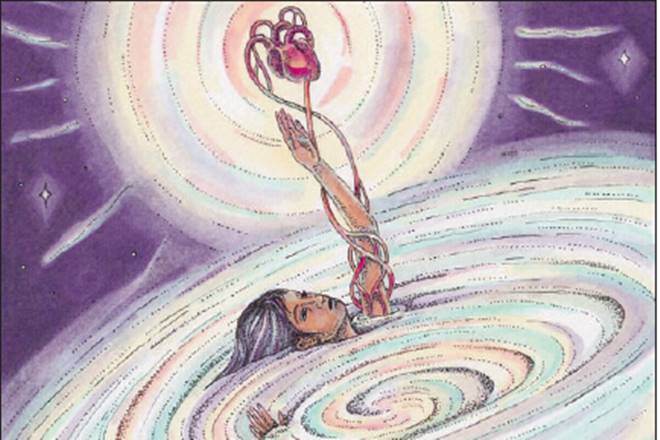

If asked to draw an illustration based on the above mini ‘story’, what would you draw? UK-based artist Gavin Strange came up with an illustration of a resplendent full moon shining over a dark lake, reflecting the moon as a broken heart, while Indian artist Priyesh Trivedi depicted a lone man sitting by the riverside with a paper boat in his hands. Strange and Trivedi were just two of the seven artists from India and the UK who were part of the recently-concluded Saptan Stories, a seven-week-long arts initiative. Saptan was a creative collaboration between British animation studio Aardman Animations and the British Council in New Delhi as part of UK India Year of Culture 2017, a year-long celebration of modern-day India and its 70-year relationship with the UK.

Concluded on September 16, Saptan was a unique celebration of art and words in which each of the seven artists—Gemma Correll (UK), Adrita Das (India), Tom Mead (UK), Janine Shroff (India/UK), Saloni Sinha (India), Gavin Strange (UK) and Priyesh Trivedi (India)—had to come up with their own unique illustrations based on the mini stories they were provided each week for seven straight weeks. The artists in question were chosen by Aardman and the British Council, which also provided them the first story brief (given above). The subsequent stories—the last line of a story influenced the next—were crowd-funded, wherein entries were shortlisted from a pool of such mini stories sent in by the Indian public on the Saptan Stories website.

For each story of the week, the artists had to submit an illustration—at the end of the seven weeks, there were seven stories and 49 illustrations, which can now be viewed on the website. Interestingly, the artists also sent in their submissions online. “We wanted to find the right balance of artists who would complement each other while also being entirely individual,” Neil Pymer, interactive creative director, Aardman Animations, says. “We looked through hundreds of artists to get to our final selection. Their breadth, range and visual uniqueness is stunning.” But what led to the genesis of Saptan? As per Alan Gemmell OBE, director, British Council, the idea came from a brief tendered by the British Council for a digital project to compliment the UK India Year of Culture 2017. “When we received the brief, we began to think of all the possible ways that such a project could unfold, whittling it down to a core idea. We decided to base it around the game Consequences, where the previous line of a story influences the next,” Gemmell says.

Reading between the lines

The availability of just a few lines to base your work on is an arduous task for sure, but also one that brings great opportunity. For Tom Mead, one of the participating artists, the time constraint—the artists were given three days after each story was shortlisted to submit their illustrations—was fairly challenging, “but good (as it allowed me) to be able to ‘compress’ what I do. Also, it made me think about what ideas were feasible in that timeframe and, if not, they were adapted to make them so,” the UK-based artist says, adding that the driving force behind any art is self-discovery. “I want to work out why I draw what I draw, so I can draw more of it. My work is based on real things that happen around me that I tend to bend and subvert to make it more pleasing for my sensibilities,” Mead explains.

Talking about the quality of the artworks submitted, British Council’s Gemmell says, “There have been so many creative and thoughtful submissions… it would be unfair of me to pick favourites, but the ones that really stick out are those that are visually strong and move the story on.” Mead says he enjoyed working alongside the other artists. “It would be great to be part of an even bigger project like this in the future,” he says. Talking about the differences in the styles of the Indian and British artists, Mead says the use of colour was the key differentiator—the work of Indian artists was very colourful. “A stark contrast to what I do. Also, they seemed to be rich in hidden meanings, which was really interesting… you gained more from second and third glances,” Mead says.

Culture, societal norms, education, etc, all contribute to an artist’s work. But it’s the variety in the inspirations that sets each of them apart. “Artists are visually influenced from the world around them and this will always vary, depending on the circumstances they find themselves in,” says Aardman Animations’ Pymer. “However, there are universal themes that are prevalent the world over and these themes reappear no matter what culture you are from.”

Rise of digital art

The online space gives artists the chance to showcase their work the world over with very little investment. Also, with social media, artists can connect with like-minded people. Mead thinks audience engagement is really important for an artist. Saptan was a success in this respect as it engaged with the audience all through the seven weeks. “Often, people just see the final product, so it was really interesting (for them) to see the developmental stages as well… It’s the type of project that would be amazing to expand to other countries or have it last a year.”Mead, however, also confesses to being occasionally overwhelmed by the digital space. “I try and turn all computers off one day a week, so I can focus on things like reading and drawing,” he admits. “It’s important to have a good grasp of the real world as well. Face-to-face contact and going to art shows are important. Otherwise you can end up sitting alone in a room staring at a screen for the rest of your life,” he says.