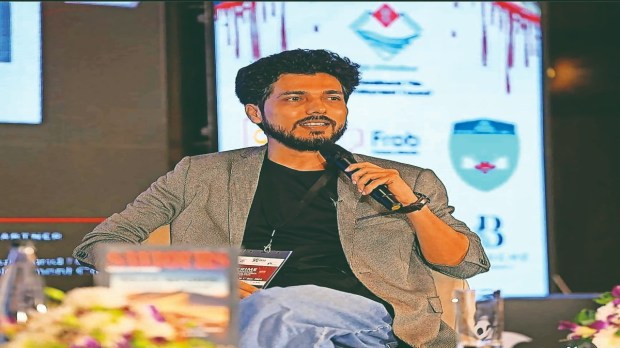

‘Crime fiction does impact society’s psyche, but on a very negligible level’: Avinash Singh Tomar, screenwriter

What was writing Mirzapur like?

It was a very collaborative writer’s room we had for Mirzapur. There was a lot of studying character arcs, we would think a lot about how we want to phase the seasons, and what gimmicks would sell. We spoke to a lot of local people as well. We took a pragmatic approach as to what the viewers would want to see.

Mirzapur has become a cult show over the years. Where did your inspiration to write this show come from? And did writing so much crime and gore ever get to you?

I come from Uttar Pradesh, so whatever I wrote were things I’d been observing from an early age. I have not committed any crime (laughs), but I’ve seen this ecosystem up close and been a part of it first hand. So the authenticity was pretty easy for me to get a hang of. What I would say is that you have to know your palette and your audience. So you have to use your imaginative acumen to give the show a flavour that the audience would want to come back to.

Writing crime fiction doesn’t take a toll on you, it’s actually the opposite. Violence is such a strong and intense emotion, that when you’re writing about it, it’s almost as if you are venting it out of your system which feels pretty cathartic. Writing, in itself though, is a very exhausting job. It’s the good kind of pain though.

Do you think anyone other than Pankaj Tripathi would have been able to justify the role of Kaleen Bhaiya?

Once you put an image to some character and then go and see in retrospect, it’s always difficult to imagine someone else playing the part. You can’t imagine anyone other than Amjad Khan as Gabbar from Sholay (1975). There are a lot of actors I know who would have done better, but would it have landed that way? You can’t say for sure. The magic that happens on the screen happens.

How do you perceive the way Mirzapur has impacted our society?

Crime fiction does impact society’s psyche, but on a very negligible level. If you are a lost person, you might do certain things (after seeing them on screen) because you might feel validated. People do get influenced by toxic or violent characters because they want to validate their own actions. That’s the unfortunate reality of our times. But as creators, we cannot curtail ourselves from telling a story. It’s also our right to tell a story the way we want to.

What next will we be seeing from you?

I’ve written a couple of films that I’m pitching to producers. There are some other projects I’m working on. One of them is a crime drama, so I’m pretty sure I’m going to typecast as a crime writer, even though I’m a very comedy-loving person (laughs).

—

‘From Wasseypur to Gangs of Wasseypur, the journey is of a very simple man who just wants to tell his stories’: Zeishan Quadri, writer and actor

Tell us about your journey.

From Wasseypur to Gangs of Wasseypur, the journey is of a very simple and ordinary man who just wants to tell his stories. I grew up in Wasseypur (Jharkhand) and completed my higher education from Meerut. I went on to work at a call centre in Noida, but when the recession of 2008 hit, I moved to Mumbai. I initially wanted to be an actor, because growing up, I would dream of cinema and Salman Khan would be in the back of my head, no matter what I was doing.

When I started living in Mumbai and got more exposure to the film industry, I decided that I wanted to write the story of Wasseypur, and by chance, I met Anurag (Kashyap) sir. I narrated the story to him and he liked it.

Gangs of Wasseypur became a cult film soon after its release. After the film’s success, did things come easy to you in the industry, or was there pressure to recreate the kind of triumph that the movie enjoyed?

Meeting people became easy, but the pressure was that people wanted to recreate the film but couldn’t. Not everyone has the courage or the guts that Anurag sir has, to not care about whether the film is a hit or a flop, or what critics might say. It’s courage that ends up in films like Gangs of Wasseypur, or Haasil and Paan Singh Tomar (2003 and 2012 films by Tigmanshu Dhulia).

You’ve often mentioned that you grew up seeing whatever you showed to the world in GoW in 2012, and in Meeruthiya Gangster in 2015. Since you wrote and acted in the films, did reliving the same things affect you?

Once you have written a story, there’s nothing more left to do with it. What does affect me as a writer is telling stories that I haven’t lived, telling stories that are new to me as well. Because that’s when I really get to think, research, and then really use my creative acumen in the way I might want to present it to viewers.

With stories you know of and you’ve lived, you let go as soon as they’re made; then they belong to the audiences.

What role do you like yourself in more —as a writer, actor, or director?

I really like myself as a writer, because directing every film you write is also not possible. I’ve written films like Revolver Rani (2014), Chhalaang (2020), and Halahal (2020), too, that I’ve not directed. That said, directing a film like Meeruthiya Gangster was a joy in itself.

As an actor, when projects come to me, some of them really interest me. But writing is what I love doing the most any day.

What next will we be seeing from you?

It’s too early to divulge any information on this, but as of now, I’m working on a crime film based in western UP.

—

‘There’s good and bad, and worse, and humans are still capable of doing anything’: Filmmaker Prakash Jha

Where does your inspiration to tell the kind of stories you do come from?

I keep watching, looking, and experiencing everything that happens around me, just like everyone else. But there are some things that strike me as a little different, and then they keep on occurring in different forms. I keep noticing them all around me. For instance, if you look at the relationship between the police and society or the criminal and society, it’s an ever-evolving thing. Crimes will continue to happen, cases will continue to be lodged.

What interests me is how a criminal is manufactured in society. You aren’t born a criminal, but you commit a crime, and then you start enjoying it, and you find a following for yourself. This is something that interests me—how criminals are worshipped or why they enjoy the following they have, how they become the criminals they are. So this is something that made me curious and I studied how society benefits from criminals and crime, and that is how I came up with the story of Apaharan (2005). I’m constantly inspired because my inspiration really comes from life.

It’s been 21 years since Gangaajal. A lot of what you showed in the film, like police encounters and extrajudicial killings, is now glorified. Do you think you’d make a film like that today?It (extrajudicial killing) was always glorified, even back then. It’s not anything new. A film like Gangaajal is always needed. Because the underlying factors might have changed—media, social media, overpopulation, unemployment —due to which society has become far more interactive. But man’s behaviour has not changed. It has always remained how it was. There’s still good and bad, and worse, and man’s still capable of doing anything.

When you make social dramas, how do you balance between glorifying crime and condemning it?

I don’t judge my characters or my story. I simply put things the way they are. What I do try to do is leave the conclusion with some sort of hope that goodwill will win.

What next will we be seeing from you?

There’s a feature film I’m working on and there’s a web series that might go live on OTT next year.

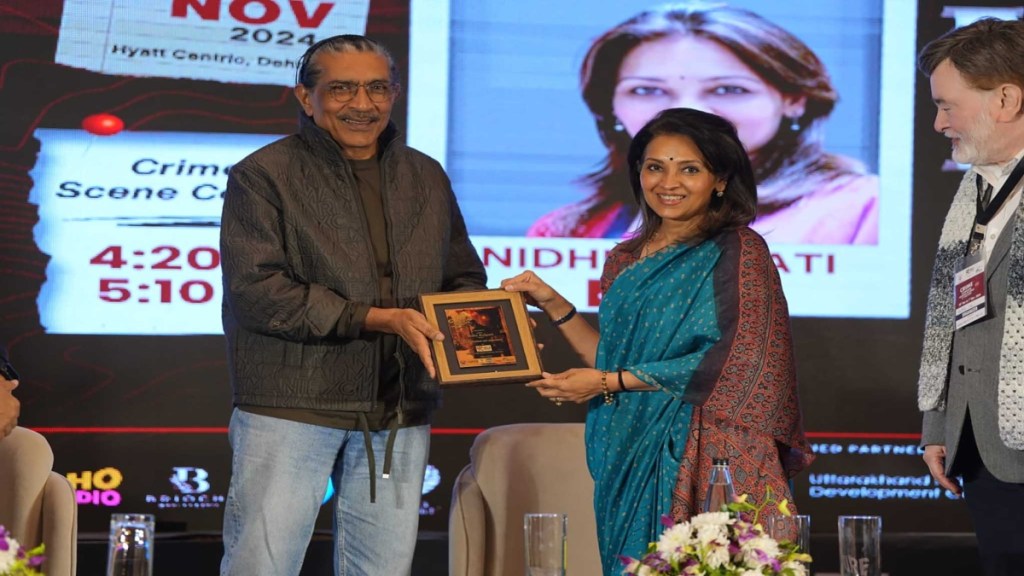

The interviews were conducted on the sidelines of the recently-concluded Crime Literature Festival in Dehradun