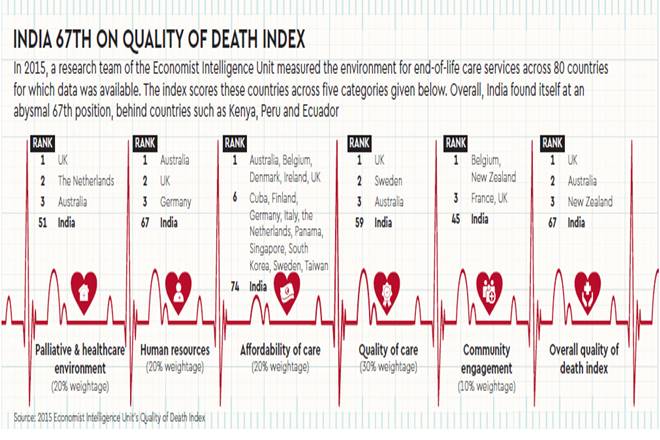

Sixty-five-year-old Sita Devi has a blank gaze on her face as a nurse attends to her inside the palliative care unit (PCU) of the Dr BR Ambedkar Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital (IRCH), which is housed inside the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi. A cancer patient, she is in such a state that all she waits for is the next dose of pain relief medicine. But Devi can be called lucky, as she is one of the few fortunate people getting palliative care among the six million in India who need it. The situation of palliative care in India is abysmal, to say the least. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU’s) Quality of Death Index 2015 places India at the 67th position among the 80 countries that were surveyed to assess the quality of death. Media reports have even claimed India to be one of the worst places to die in. Even the ward in AIIMS, which sees an inflow of lakhs of patients, has just six beds. The concept of palliative care is relatively new to India, having been introduced only in the mid-1980s. Since then, hospices and palliative care services have developed through the efforts of committed individuals, including Indian health professionals and volunteers, in collaboration with international organisations and individuals from other countries. There are about 1,400 palliative care centres in the country for the six million in need—one centre for about 4,300 patients.

This reiterates the disproportion in the number of institutions offering palliative care vis-à-vis those requiring it. Many medical professionals and hospital staff are not even aware of the term ‘palliative care’. While searching for the PCU in AIIMS, I was told to enquire at the reception of the academic block. An initial enquiry elicited no response and when asked the second time, the staffer at the counter conveyed in an irritable tone, “There is nothing like a PCU here. There doesn’t exist one. You must be mistaken.” As per the World Health Organization (WHO), palliative care is a multi-disciplinary approach that improves the quality of life of patients with life-threatening illnesses, and their families by relieving suffering and pain—physical, psycho-social and spiritual. But one needs to understand that palliative care is not a facility exclusive for terminally ill patients, but for anyone in need of severe pain management, and also counselling. The country’s inability to consider death an inevitable phenomenon and talk about it within the family and outside is one of the major social hurdles palliative care faces. The ailing healthcare sector, courtesy the perennial shortage of funds, infrastructure and medical professionals, just compounds the problem. Even the availability of morphine as a painkiller, despite a 2014 amendment to the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, is an issue.

As per recent statistics, only 2% of the people get palliative care in India against a global average of 14%. Palliative care does not feature among the top priorities of Indian doctors, who are too busy battling diseases to worry about offering pain relief or emotional balm. Of the six million in need of palliative care, a majority of them are suffering from cancer (80% of the one million new cases in India come for treatment at an advanced stage). Also, there are conditions—AIDS, muscular dystrophy, dementia, multi-organ failure, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease, end-stage renal disease, heart diseases, permanently bedridden patients and people with neurological problems—that are in desperate need of such care. MR Rajagopal, chairman, Pallium India, a Kerala-based palliative care NGO, believes the situation in the country is lamentable and, surprisingly, the rich are not better off than the poor. Rajagopal, often referred to as the ‘father of palliative care in India’, says, “The rich probably have a worse kind of suffering. Except a few, most so-called excellent hospitals do not offer pain relief. They (patients) are all subjected to inappropriate intensive care. This means that in addition to the pain, they also have to suffer isolation at the end of life without having people close by or a human touch.” Nagesh Simha, medical director, Karunashraya—a palliative care hospice for advanced-stage cancer in Bengaluru—adds, “An enormous effort has been made by everyone concerned—the ministry of health, palliative care service providers, the Medical Council of India having recognised palliative medicine as a specialty—but considering the huge population of our country, we still have a long way to go.”

States in the south of India, including Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, are the flagbearers of hope for those in need of end-of-life care, as over 90% of the palliative care centres in the country are located in these three states. For instance, the Institute of Palliative Medicine, Kozhikode, was one of the earliest end-of-life care centres in the country. Started in 1993, the centre does not limit itself to providing palliative care to patients, but has made significant contribution to the overarching issues of policymaking and generating awareness as well. What started in Kerala has trickled to other parts of the country too. Suresh Kumar, director, Institute of Palliative Medicine, Kozhikode, thinks of their role as a social catalyst. “We have worked with the Kerala state government and the people to make palliative care a part of the lives of people. We told the people that irrespective of their profession, they would have to take up certain forms of palliative care,” Kumar tells Financial Express. He adds, “We have expanded to other states and countries as well. We have been running a similar project in Puducherry for the past two years. We have similar projects in Imphal, Manipur and in Nadia, a border district in West Bengal.” The organisation has its footprint in other countries as well, including Bangladesh, Thailand, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Any palliative care institute has three basic programmes to deliver such care—out-patient clinic, home care and in-patient clinic. So how does such a facility function? Kumar explains: “We register the patients at the out-patient clinics, and depending upon their location, we link them with the home care services. If the patient is in Kerala, it is easy to tap the network we have already established. Once the patient is in home care, they are regularly visited by a team comprising a nurse and community volunteer.” However, if the patient is in need of hospitalisation, he/she is brought to the in-patient clinic. “We encourage them to stay at home as much as possible. But in cases where this is not possible, they are brought to the in-patient facility,” explains Kumar.

Just like the Institute of Palliative Medicine, Karunshraya, too, is engaging deeper with the cause to bring about a change. Started with the aim to take care of only cancer patients, the organisation is venturing into other fields as well. “Education is an important aspect for us. For that, we have been working with the University of Cardiff, the National Institute of Medical Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), the Union ministry of health, and the health ministries of Karnataka and Odisha. We have been conducting training programmes for doctors from different states as well,” Simha tells us, adding that they are going to tie-up with a hospital in Bengaluru to offer palliative care to patients suffering from kidney-related diseases as well. DEAN Foundation is another such organisation working towards palliative care in Chennai. With its head office in Kilpauk, an out-patient clinic and home care facility, it has its out-patient facility at the Government Children’s Hospital, Egmore. Its chairman, Deepa Muthaiya, says, “Since our inception in 1998, we have taken care of over 11,000 patients, of which most have been cancer patients. Over 90% of our patients are from very poor socio-economic backgrounds.” On an yearly average, over 1,000 patients are referred to the institute. “Referrals are from doctors, or through patients and their families, through our website, from other NGOs, medical institutions, etc,” says Muthaiya. Interestingly, unlike pocket-burning treatments in an ICU or life-support system, palliative care services here are absolutely free.

Hospitals follow suit

With the palliative care sector slowly moving forward, courtesy independent NGOs and institutions, major private and public hospitals are also following suit. For instance, Bengaluru’s Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology started a specialised palliative care cell in April last year. The move came after the hospital witnessed a large number of people demanding palliative care and oral morphine every year. Max Hospitals has also come up with its home care service called ‘Max at Home’. Rohit Kapoor, senior director and chief growth officer, Max Healthcare, claims it to be a technology-enabled home care service, which has about nine facilities across the National Capital Region alone. “More than 300 people work for it and last year, we saw more than 20,000 patients,” says Kapoor. He explains that the initiative is now fully capable of providing comprehensive home care palliative care services in the NCR. “This means linkage to doctors and nurses catering to patients; setting up the equipment needed at home to monitor them, etc.” Fortis, another private player in the healthcare sector, provides palliative care services to its cancer patients. Vinod Raina, executive chairman, medical oncology and haematology, Fortis Gurugram, considers the lack of specialised hands as one of the inhibitors in providing palliative care. “For doctors in our country, a majority of the time goes in treating a disease and not eliminating pain. We need more specialised hands,” he laments. When asked as to why the country has such an acute shortage of specialists for palliative care, Raina points out a major flaw in our medical education system. He adds, “We do not have specialised courses for palliative care in our undergraduate or postgraduate courses.

Only a handful of the universities provide such courses. This results in our doctors not being specialists.” When it comes to government hospitals, the situation is worse. At AIIMS, a junior resident tells us, “Though the palliative care unit was started a long time back, we have only six beds. There are days when we have to choose patients in the OPD ward to be provided palliative care. It’s disheartening to look at those who are left out.” On asked as to how the selection is made, he adds, “The ones in more pain are given preference.” Talking to Financial Express, Sushma Bhatnagar, head, department of onco-anaesthesia, pain and palliative care at AIIMS, says the dedicated unit has six doctors along with residents and postgraduate students, adding, “The unit has started providing services to patients with non-malignant diseases as well.” Bhatnagar believes palliative care should be started from the first stage of a disease itself to alleviate pain. “It is not just for terminally ill patients. One should start with it very early to let the patient acclimatise to the procedure. That is what we do here. If they start getting it towards the last stages, they realise that their end is near.” As for morphine, she says the hospital maintains its stocks well by regularly tracking supplies. “I make sure the invoices of the supplies come directly to me. It makes it easier for me to tally it with the demand we have. In case we fall short, the order to the vendors is placed with a higher demand for morphine to compensate the deficit,” she adds.