A company that grew while everyone looked away.

Imagine if you could walk into a Hindustan Aeronautics Limited campus, we are sure the first thing you would find is this peculiar blend of old India and new India sitting side by side.

You would still probably see the timeless brick sheds where early MiG components were machined. And just a few steps away, rows of digital machines would light up, while engineers watched live feeds from robotic fabrication bays where the new Tejas jets are assembled millimetre by millimetre.

HAL has always been here, always been large, and crucial. But because it seldom made noise, it also became unseen, stuck in that trap of India’s memory kept for government companies that just exist.

Yet behind that invisibility, the numbers tell a different story. HAL now pulls in an annual revenue (trailing twelve months) of ₹32,105 crore and earns ₹8,469 crore in profit. Numbers that would surprise investors who still think of this behemoth as a slow public sector unit.

For a company that once fought to break the licence-production approach, those operating margins, over 20% constantly, are the kind most businesses would covet..

HAL didn’t change all at once. It progressed in the shadows. And this quiet transformation is what makes its story even more fascinating.

The decade HAL silently redid Itself

Every story has an inflection point, and HAL’s came just when India was restructuring its defence path.

While private defence setups contested for awareness and global giants eyed India’s buying budgets, HAL did something very un-HAL-like. It began revolutionising soundlessly, rapidly, and without waiting for approval.

A few older engineers talked about the shift, almost like it was a change in ethos. “We stopped thinking like a licence producer and started thinking like a designer,” as V. Geoffrey, the MD of MiG project, then said in an interview.

The proof of that change lies in HAL’s order book: over ~ ₹2.5 lakh crore currently.

The Tejas Mk1A alone produced an order pipeline for the next few years. Include the Light Combat Helicopter, the HTT-40 trainer, engines, the Dhruv ALH, aircraft improvements, and global orders, and suddenly, HAL is no longer the PSU waiting for orders; it has become the core of India’s defence force.

During these years, HAL’s return ratios also grew. The average return on equity (ROE) stands solidly at 27% over the last three years. A level most customer-focused companies pursue. Ten years ago, no investor could have foreseen the change HAL has undergone.

When deep-tech became real

Investors seldom talk about HAL as a deep-tech enterprise. But look closely, and you find that deep-tech is the only dialect it has ever communicated through.

Most of the new-age deep-tech startups are still at the virtual reality phase in India. HAL, in the interim, is producing avionics, complete plane systems, fusions, flight-control algorithms, and engines, every day, at scale.

And while that culture existed before, it was the Tejas program that forced HAL to become truly modern. Of course, the learning curve was challenging, chaotic, and long. But it built something far more valuable: a company that could now create its products in-house.

This is not a tiny change. A company making approved airplanes is expendable. A company making its own plane is perhaps untouchable.

And that’s what most missed noticing. HAL did not develop into a new-age defence company because it wanted to contend with other players in the sector. It became one because India required it to.

The CAPEX showed up in the numbers too, ~ ₹2,026 crore spent in FY25, chiefly on materials for the Greenfield Helicopter project at Tumakuru, improvements on LCA, and routine overhauling facilities for SU-30 and AL-31FP engines.

It plans to invest ~ ₹14,000-15,000 crore in the next five years to expand its production capacity and build additional routine overhauling facilities. It is a sign of scale that didn’t exist before.

Built on time, trust, and government deadlines

Here’s something most people overlook. Defence companies aren’t built by selling more. They grow by trading in long-term systems. A jet is not just a product, it’s a three-decade association.

HAL’s business works like that. When it supplies a helicopter or trainer aircraft, the sale is just the starting point.

Parts, service, improvements, average-life revamps, engine refits, these become recurrent income streams. This is why HAL’s operating margins sit comfortably above 24%, and why its cash flows are expected even in downturns.

Unlike private manufacturers, HAL doesn’t devote billions to advertising worldwide. That’s why its debt is zero, a rare feat for a business that manages such long program runs.

What tale the numbers weave?

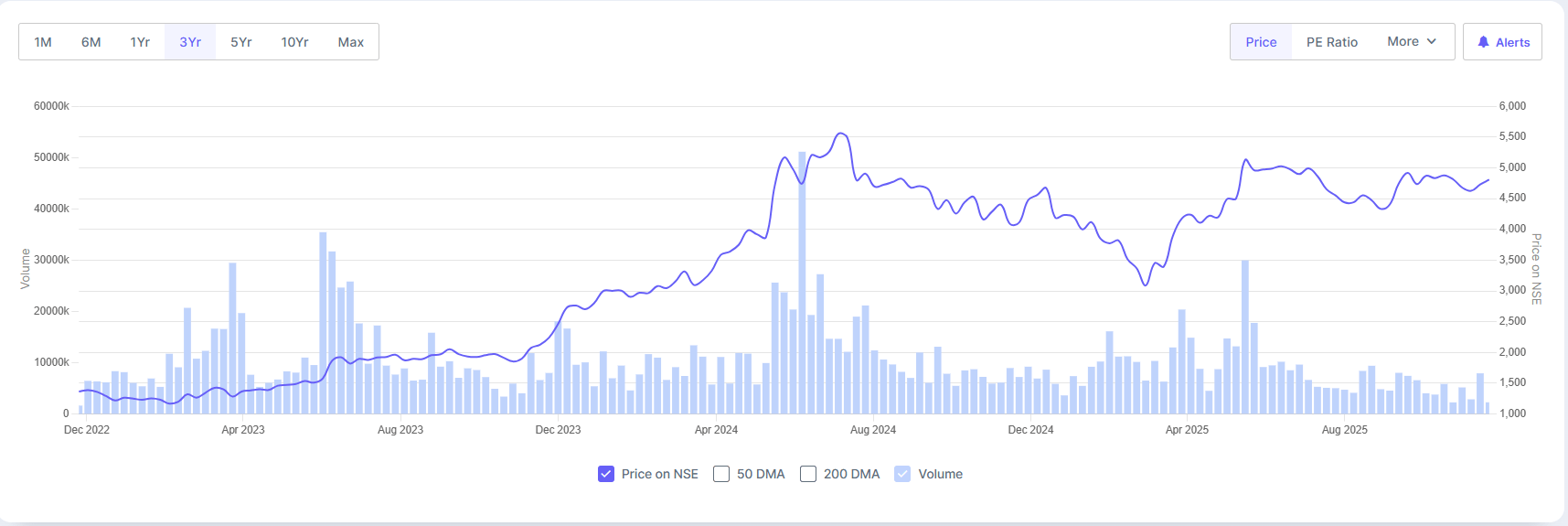

If you look at HAL’s last three years, the compounded profit growth has been ~18%,while the share price grew at a CAGR of 53% in the same period.

3-Yr Stock Price Trend (Dec 2022-Nov 2025)

The company is sitting on cash reserves of ₹36,780 crores as of September 2025, as per Screener. HAL’s valuation was once a tiny afterthought; today, its market cap is ₹3,18,380 crores; this is 12.3 times of what it was just five years ago.

But unlike FMCG or IT companies trading at high multiples for hope, HAL is valued so highly because its order book is locked for years, its profit margins are balanced, its cash flows are substantial, and its deep-tech advantage is incredibly difficult to imitate rapidly.

Despite its numbers and earnings, its P/E of 37.6x is below the sector median of 68.3x. and the EV/EBITDA of 21.44 is lower than the industry median of 37.07, which makes it a relatively undervalued play in the defence stocks line-up.

This scenario is not the financial path of a sluggish PSU. This is the track of a machine that knows how to expand without sound.

The export engine nobody expected

Historically, HAL was never known as an exporter. But the past few years saw a change once the Dhruv chopper and LCH had matured.

Today, HAL exports airplane and chopper spares to several countries with training and service contracts for years ahead. HAL’s export revenue, though relatively small ~ ₹493 crores in FY25, has started increasing.

The company’s current pitch to Southeast Asian and African markets isn’t an advertising trick; it’s an extension of a really slow, systematic plan that is finally paying off.

Exports matter as they signify the final stage of HAL’s transformation: from a trader → to a maker → to an original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

If Tejas Mk1A and Dhruv clear a few more international demos, HAL’s export report will look very different five years from now.

Built for a future that ultimately came

There’s a novel paradox in HAL’s narrative. For years, India’s private sector taunted PSUs for being slow and fixed. But the world we live in now, scarcity of airplanes, increasing geopolitical risk, and India becoming a major buyer, have created the perfect atmosphere for the one PSU that never rushed into something.

HAL’s gradual speed became its power. Because it built expertise one brick at a time, years before anybody cared. Because it understood how to lead long-cycle engineering programs. Because it knew how to supply aircraft safely, not quickly.

Every Indian defence company wants to be HAL. But very few can do what HAL does. That’s the real advantage.

The only risk that actually matters

With a story this strong, investors often wonder about one thing: What if order flows slow down?

It’s a fair question.

HAL’s wealth rests on government schedules. Any interruption in Tejas Mk2, AMCA, or helicopter purchasing can slow the drive.

Longer defence product cycles also mean HAL cannot pursue hypergrowth the way private tech companies do.

Other risks also include dependency on some associate partners, such as General Electric, for engines. A delay on their part could affect the production cycles at HAL.

But here’s the other side of this: HAL has more visibility than any company in the Indian market today. When you have ₹2.5 lakh crore worth of work already lined up, as mentioned in the Indian Aerospace & Defence Bulletin, you aren’t estimating the future; you’re simply implementing it.

The only real risk is the implementation rate. But the HAL of today is not the HAL of 2010. It learns fast, digitalises quicker, and creates with more accuracy than ever before.

A soundless giant finally stepping into the light

HAL didn’t reinvent itself through slogans or speeches. It did it the tough way, by providing program after program, year after year.

Its transformation wasn’t loud. It wasn’t glitzy. It wasn’t even noticeable until the numbers made investors sit up. But now, there’s no overlooking it.

A company once forgotten as an old PSU has turned into one of India’s greatest deep-tech engines, a consistently profitable defence titan, and one of the few space firms with a 20-year order runway in the world.

For India, that matters: HAL’s transformation is a microcosm of a bigger story, the country’s push to build its own advanced defence technology, not just to assemble.

For investors, HAL is no longer just a safety play on a PSU; it could be the bet on India’s future in defence innovation.

The story isn’t that HAL changed. The story is that India finally changed enough to notice. The Sky is No Longer the Limit

Disclaimer:

Note: We have relied on data from www.Screener.in throughout this article. Only in cases where the data was not available have we used an alternate, but widely used and accepted source of information.

The purpose of this article is only to share interesting charts, data points, and thought-provoking opinions. It is NOT a recommendation. If you wish to consider an investment, you are strongly advised to consult your advisor. This article is strictly for educative purposes only.

Archana Chettiar is a writer with over a decade of experience in storytelling and, in particular, investor education. In a previous assignment, at Equentis Wealth Advisory, she led innovation and communication initiatives. Here she focused her writing on stocks and other investment avenues that could empower her readers to make potentially better investment decisions.

Disclosure: The writer and her dependents do not hold the stocks discussed in this article.

The website managers, its employee(s), and contributors/writers/authors of articles have or may have an outstanding buy or sell position or holding in the securities, options on securities or other related investments of issuers and/or companies discussed therein. The content of the articles and the interpretation of data are solely the personal views of the contributors/ writers/authors. Investors must make their own investment decisions based on their specific objectives, resources and only after consulting such independent advisors as may be necessary.