By Srinath Sridharan

When Ada Lovelace mused that the first mechanical computer “could compose elaborate pieces of music” if instructed properly, she planted the seed of a question that has since obsessed generations: what happens when the tool starts to think? In The Shortest History of AI, Toby Walsh compresses nearly two centuries of that pursuit into a brisk, lucid 203 pages—a kind of intellectual time-lapse of humanity’s most ambitious experiment.

The book opens not in Silicon Valley, but in Dartmouth college in New Hampshire, US, on June 18, 1956. The day when the legendary AI guru John McCarthy convened a group of like-minded academic colleagues for an eight-week-long workshop to build intelligent machines. Well, it is him who coined the term “artificial intelligence”.

Walsh argues, the story of artificial intelligence is not about sudden leaps but about patient accumulation—“many so-called overnight successes”, he writes, “were decades in the making”.

That line captures both the tone and the thesis of the book. AI, in Walsh’s telling, is no meteor that recently struck human civilisation; it’s a slow-burning fire that we have been stoking for generations.

The book’s structure—six essential ideas that ‘animate’ AI—gives this short history its backbone. Those ideas are: symbol-manipulation, search and optimisation, rule-based reasoning, learning from experience, reinforcement and correction, and probabilistic inference. Together they read like the DNA strands of machine intelligence.

Walsh, a veteran AI researcher, has the gift of making complexity conversational. He can sketch in a few lines how the “symbol-processing” dream of the 1950s birthed both optimism and hubris, or how neural networks, once discarded as dead ends, rose again to power the age of deep learning.

The writing glides smoothly like a well-oiled algorithm—fast, clear and occasionally cheeky. “We’ve built machines that are better at arithmetic, memory and now at attention,” he notes, “but we’re still the best at being human.”

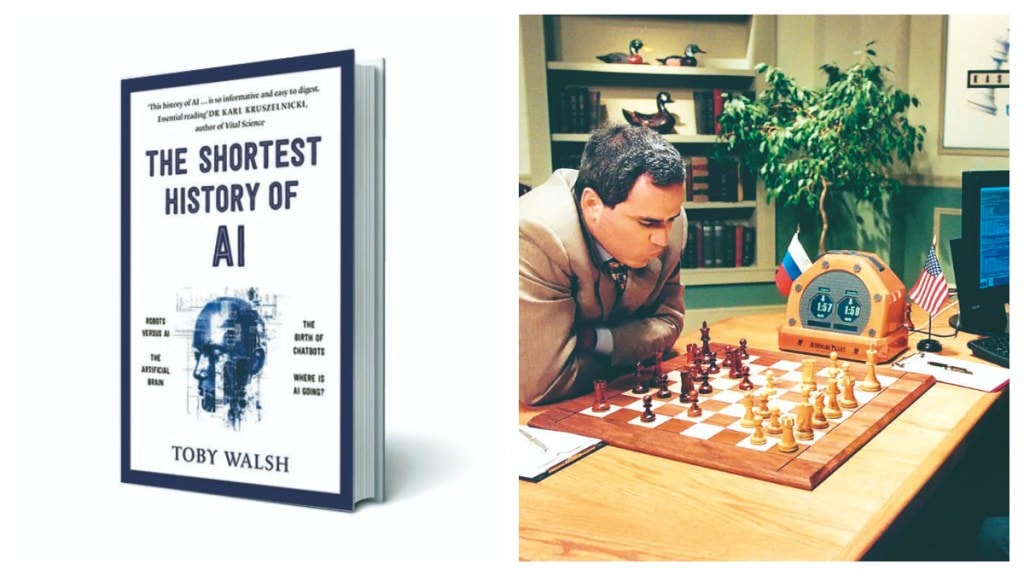

The reader encounters familiar icons —Turing’s imitation game, Deep Blue’s victory over Kasparov, the eerily creative feats of ChatGPT—but Walsh’s eye is always on what each moment reveals about ourselves. When a machine writes a sonnet, he asks, is it performing intelligence or merely performing us?

In one of the book’s most striking passages, he recalls how AI once cycled through boom and bust, from the “summer of expectations” to the “winter of disillusionment”. Each wave promised salvation and delivered something more mundane—a faster lifesearch engine, a better spam filter, an app that recognises cats. “We dreamt of electronic brains,” Walsh quips, “and we got recommendation engines.” The triumph of AI, he reminds us, lies not in replacing human intellect but in amplifying it.

He is also refreshingly candid about AI’s limits. “The machines we have today are idiots savants,” he writes, “brilliant at one thing, brittle at most others.” They can compose a poem but fail to grasp irony, diagnose disease yet misread context, ace a game but stumble in a corridor. Walsh’s six-idea framework repeatedly exposes this paradox—extraordinary competence within narrow walls, and near-total confusion outside them.

The promise, the peril, and the pause Walsh positions himself as both historian and moral witness. He sees AI not as an alien force but as an artefact of human choice. “We use tools; they don’t use us,” he reminds the reader. And yet, he warns, the boundary is thinning.

The closing chapters are suffused with quiet urgency. As AI begins to write news, mark essays, approve loans and even simulate empathy, Walsh asks whether societies can keep pace with the moral consequences of their inventions. “Our children,” he cautions, “are set to inherit a worse world than the one we were born into—some of it of our own making, some of it shaped by the machines we built to help us.”

Walsh neither glorifies nor demonises AI. Instead, he dissects it with a scholar’s precision and a citizen’s concern. He reminds readers that the real contest is not between humans and machines, but between our better and lesser selves: will we use intelligence—artificial or otherwise— to enlarge human flourishing or to entrench inequality?

His anecdotes are especially resonant for a business-minded readership. He recounts how, in 2016, AlphaGo’s creative move against world champion Lee Sedol stunned experts because it was not a calculation but an intuition—a hint that machines might soon out-intuit us. Or how early rule-based “expert systems” in the 1980s promised to automate diagnosis and law, only to collapse under their own rigidity. Every technological high has been followed by a sober reckoning.

“We must stop teaching our children to compete with machines,” he writes, “and start teaching them to do what machines cannot—to question, to care, to imagine.” It’s the sort of line that lingers after the last page, as apt for boardrooms as for classrooms.

For all its brevity, Walsh covers enough ground to make the reader wiser, not just better informed. The prose moves between wit and warning with agility. There’s humour in his account of a 1950s AI programme that “took ten minutes to recognise a triangle,” and poignancy in his observation that “machines are learning faster than societies are adapting.”

The pleasure of reading this book lies not only in what it explains, but in how it makes us pause. Like a well-designed algorithm, it leaves no wasted motion. Each of the six ideas becomes a lens through which to examine not just what AI is, but what it reveals about us: our longing for control, our impatience with limits, our faith in progress. Toby Walsh’s elegant six-idea history of AI reminds us that the future was a long time coming—and that the hardest problem in intelligence may still be the human one.

As a smooth read, it satisfies both curiosity and conscience. It gives the general reader a map of how we arrived here —from Babbage’s gears to Google’s neurons—and it gives the thoughtful reader a mirror for what may come next. The brevity is deceptive: it condenses a century of hope and hubris into a few potent chapters. And Walsh also says for AI to match human intelligence, it will, “over the next 10, 50 or perhaps 100 years”.

A must-read book, also with fun-filled trivia and insights, for all ages, including young adults.