For Goa-born Mayuri Chari, art is all about celebrating women, and her narration always focuses on the real— “real society, real people, real stories”. Her artwork, My Body, My Freedom, for instance—made using thread embroidery on cloth—depicts her conversations with her own body.

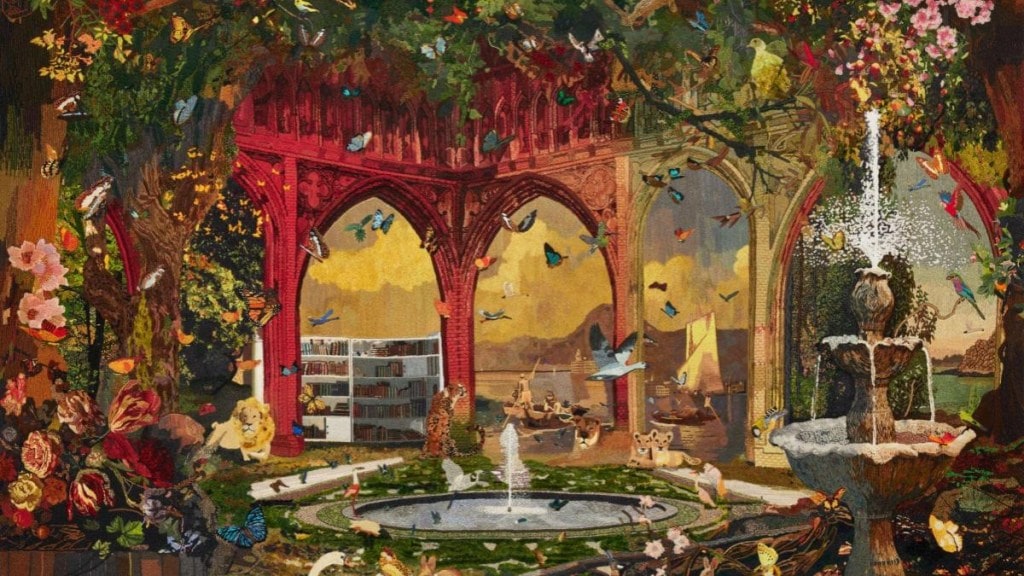

Similarly, multimedia artist Ranbir Kaleka’s Guardians in a Dystopic Garden, made in cotton and silk thread technique, confronts the divine order of ‘Arcadian Garden’ with human conquest and control.

Even though My Body, My Freedom and Guardians in a Dystopic Garden are contrasting creatives, they both run through a common thread—that of thought-provoking and visually compelling art created on textiles.

From aari and zardozi techniques to satin stitch, phulkari, Kutch embroidery, and French knots on handwoven silk, organza, khadi, jute and linen, artists like Chari and Kaleka—whose artworks were on display at the recently concluded India Art Fair in New Delhi—are trying to preserve, revive and conserve art on different textile mediums.

“The interplay of art and textile not only elevates the realm of hand embroidery to an authentic art but also throws light on the genius of embroiderers and embroidery schools that India is revered for globally,” says Gayatri Khanna, founder of Mumbai-based embroidery atelier, Milaaya, whose recent exhibition, titled Threaded Visions: Contemporary Embroidery for a Sustainable Future, was curated by Mumbai-based art curator Arshiya Lokhandwala in collaboration with Delhi-based art collector Shalini Passi at the India Art Fair.

“A slowly dying heritage, hand embroidery, when transformed into art, makes these museum pieces accessible to many, ensuring that a craft is kept alive in our collective consciousness,” adds Khanna.

As a curator, Lokhandwala handpicked the most iconic works of masters and contemporary artists including SH Raza, Ram Kumar, Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, Nilima Sheikh, KK Hebbar and Ranbir Kaleka and converted them into hand-embroidered masterpieces, addressing issues like sustainability and climate change.

Every work reflects an exploration of environmental concerns, advocating for sustainable practices such as recycling, the use of renewable fuels, water conservation and the preservation of biodiversity in the animal kingdom.

Similarly, Chari uses hand embroidery on cloth to express the illusions connected with the female body. She brings hard-hitting conversations stitched on cotton, where she re-appropriates the Portuguese legacy of trousseau stitching, adopted by her family in Goa, during colonisation and uses it as a vocabulary of feminist dissent.

The textile-artist recently set up a studio space in a village called Anur, in Kolhapur in rural Maharashtra, to spend time with rural women labourers working in sugarcane fields and to explore stories of labour camps.

“Women use their sarees as walls of privacy while building camaraderie with other women from nomadic tribes like Banjaras and Dalits, who live in a multicultural society devoid of sanitation and hygiene,” adds Chari, who started her artistic journey as an embroidery artist post her Master’s degree at the Hyderabad Central University in 2017.

Today, Chari questions the personal universe of the body, and finds that sex and nudity are still a taboo in India. She has written poems about vaginas and stitched them on a huge piece of cloth by using a portable sewing machine. All these thoughts are either interwoven on textiles, made in a mural on tarp, or in the form of a multimedia documentary.

While Shalini Passi feels that “slow fashion and the conservation of craft are the strongest pillars of sustainability”, the intricate pieces not only highlight the richness of embroidery as an art form but also celebrate the diverse traditions and skills of India.

Similarly, Karishma Swali’s Chanakya School of Craft in Mumbai has collaborated with French-Cameroonian painter Barthelemy Toguo and French artist Eva Jospin to create large-scale handcrafted interdisciplinary works using a variety of needlepoint techniques.

From handwoven silk, organza, khadi, jute and linen, the craft interplays hand-spun yarns and layering techniques, along with micro variations of needlepoint techniques, including couching, bullion knots and the stem stitch.

Toguo has worked on a 5-metre-long embroidery representing a man receiving and offering water with a hundred engraved bottles filled with water from all over the world, as well as two other embroideries representing different animals highlight the use of raw organic threads and fine needle techniques. Hand-embroidery techniques such as stem stitch, back stitch, and micro-French knots are employed to achieve an ink spread similar to that found in the paintings.

“In India, craft occupies an honoured space, proving to be more unifying in human relationships than even spoken language. Through our artistic collaborations, we acknowledge the significance of celebrating communities and their material cultures, highlighting the integral role craftsmanship plays in conveying our traditional heritage and our collective identities,” says Swali.

Swali’s Chanakya School of Craft has specialisation in embroidery and crafts and has already adorned the international haute couture. Its collaboration with French artist Eva Jospin is based on unique drawings depicting landscape of architectural structures, forests, boulders and waterfalls. Swali worked with the artisans of Chanakya School of Craft for several months to realise this landscape using contemporary versions of traditional hand embroidery techniques. Over 150 variations of different embroidery techniques and over 400 shades of organic silk, linen, cotton and jute threads were used to interpret different aspects of this landscape in great depth and detail to bring it to life.