Anu Aga

Have you ever heard of a successful company in India employing permanent workers without the presence of a union and also paying living wages to all of its workers? This was initiated over two decades ago, when blue-collar workers had very limited options and, except for the few who had access to opportunities in the Gulf countries, there was no fear of attrition.

Let me introduce you to Jairam Varadaraj, a dear friend, board member of Thermax and managing director, Elgi Equipments Ltd. I was aware that Jay felt strongly about worker well-being. However, what I did not know was that not only did he implement a commendable practice of ensuring living wages for his blue collar workers for the past 26 years but also has managed to ensure that the management in his company only earned more if the workforce earned more too, since the ratio was fixed—a definite win-win!

Years ago, when I heard about this concept of having no union in Jay’s company and the method he uses to arrive at the concept of “living wages”, I requested our HR to visit them and learn from their experience. The visit was not very fruitful as our people dismissed it as a one-off phenomenon, and not replicable in Thermax where we already have a union.

Recently, at a dinner in Pune, when I spoke about Elgi and its unique way of engaging with workers, yet again another industrialist dismissed it saying that since most companies in Coimbatore majorly operate on contract labour and lack unions, making living wages a reality was possible—but it could not be replicated in Pune where unions are popular.

However, the fact is Elgi has achieved something very unique with permanent, on-roll workers.

As human beings, we come up with excuses for ideas which are difficult to implement, rather than investing our time in understanding them.

Am I implying that unions are a bad thing? Not at all. Unions play an important role in helping workers collectively fight against exploitation and work towards a common definition of well-being. However, in many organisations, negotiations with unions can take up a lot of time on both sides and there are games played with each other. A model such as ‘living wages’ can also help such union negotiations to be more transparent and structured.

Even at Thermax, in the past, negotiations between the union and management took months and, on a few occasions, even years. The strategy at some times, in the past, was to be opaque; management would offer far less than what they were finally willing to give and the union demanded a lot more than what they were willing to settle for! A meaningless game, wasting everybody’s time and energy! Over time, however, I am glad that both sides in Thermax have learnt to be more transparent and the union negotiations today are faster and based on trust.

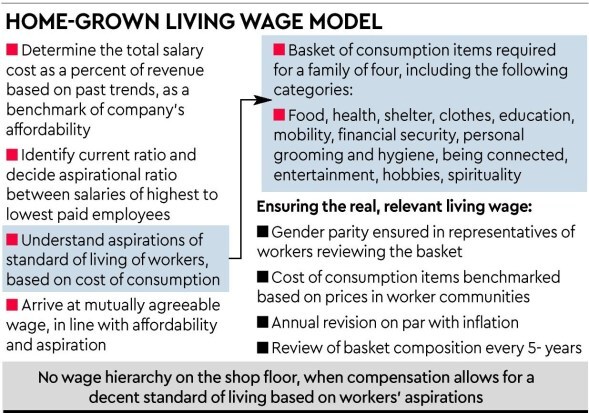

Jay’s homegrown living wage model was in response to the then-prevailing wage discussion between management and workers, which was a bizarre negotiation lacking any real basis and steered mainly by fear. And while we all, as corporate leaders, have been part of similar situations, we don’t given much thought to initiating any kind of change.

However, Elgi’s nuanced remuneration model sought to assure blue-collar workers of the life and future they aspired to while also being mindful of the affordability question for the company.

After several conversations with Jay to understand his rare model, it was evident to me that a fair remuneration to a worker in a particular place is one that is sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker and her or his family. All permanent workers in Thermax factories already earn more than living wages. There is reasonable openness and trust between the workers and management.

In a country that is grappling with complex wage regulations, and where so much of the population struggles to even earn a minimum wage, the aspiration to break India’s perception as a ‘cheap’ labour country, shaping a model that upholds the change, is truly commendable. It also busts the myth of a lower bottom line from investing in worker well-being.

It is for us, as corporate leaders, to adopt this aspiration, and adapt this model to our business set-up. Company-specific aspects—around proportion of contract labour, dynamics of a unionised environment, and size and scale of business—would require us to tweak the model to suit our context. But the inclusion of workers to co-define their needs and aspirations—the ‘why’ behind the ask for liveable wages—is the key takeaway that all businesses must try to find a way of integrating.

In Jay’s own words, the first step is to set non-negotiable goals, then identify the impediments to those, break the convention and begin the pilot. Because after all, in the long term, a responsible business is a successful one.

The Social Compact aspiration also iterates and advocates this message and invites corporate leaders to join the movement. It is about time that businesses in India adopt this broader aspiration to make ‘worker well-being’ rather than ‘cheaper labour’ our unique selling proposition in the global market.

The author is former chairperson, Thermax.