By Ashok Gulati & Reena Singh

Since the last few years, Delhi and its surrounding areas turn into a gas chamber almost every November. With the Air Quality Index (AQI) crossing the 400 mark, it becomes difficult to even breathe. According to the University of Chicago’s Air Quality Life Index Report 2023, prolonged exposure to severe air pollution could reduce the life expectancy of Delhi residents by an alarming 11.9 years. Given that the average life expectancy of an Indian is 70.62 years, it gets reduced by one-sixth; and since Delhi’s population is about 22 million, this amounts to pushing 3.7 million to slow death. This is nothing short of a self-inflicted genocide by air. We call it genocide as this number exceeds the total deaths India has suffered in all the wars since Independence. Meanwhile, our elected leaders are busy playing blame games rather than finding a sustainable solution.

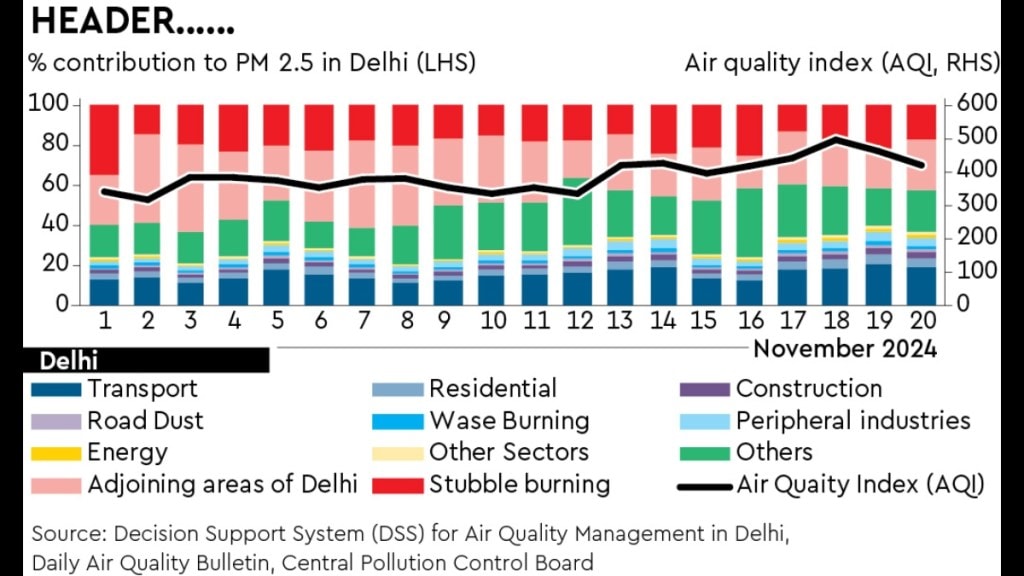

We know that as winter sets in, wind velocity slows down in the Himalayan shade, and the pollutants (PM 2.5) remain suspended in the air. But what are the sources of these pollutants during these months? According to the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, under the ministry of earth sciences, during the first half of this month, the relative contribution from stubble burning (especially in Punjab and Haryana) peaked at roughly 35.18% on November 1 (see figure). This was followed by Delhi’s transport sector contributing around 19%. Sources in Delhi impacting the particulate matter (PM 2.5) also included residential areas (~3.9%), industries (~4.6%), construction (~2.4%), road dust (~1.4%), and others (~1.2%). Additionally, neighbouring areas such as Gurugram, Jhajjar, Faridabad, Ghaziabad, and Gautam Buddha Nagar contributes 30-35%.

What policies and products can reduce this choking pollution? First, 1-1.5 million hectares of paddy cultivation in Punjab and Haryana (out of about 4.5 million hectares) needs to be diversified to other kharif crops. Both states have borne significant environmental costs to help the nation achieve cereal self-sufficiency. The Centre and the state governments are aware of this and have taken initial steps towards crop diversification. But farmers continue to grow paddy as this is the most profitable major field crop, and has least market risk due to open-ended procurement by the government.

Our research at ICRIER reveals that a significant part of paddy profitability comes from large input subsidies. In 2023-24, these subsidies amounted to Rs 38,973/ha in paddy cultivation in Punjab. But paddy cultivation in the region is massively depleting groundwater (11-12 metres in the last 22 years). It also generates greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to the tune of about 5 tonnes/ha. If farmers switch from paddy to pulses, oilseeds or millets (even kharif maize), much of the input subsidies can be saved, besides lowering groundwater depletion and GHG emissions. But farmers will switch only when their profitability in competing crops is similar to that of paddy, and market risk is minimal.

Under the current schemes, Punjab and Haryana offer Rs 17,500/ha to farmers who switch from paddy to other crops. But this incentive is only for a year, and is too small to make profits that equal paddy profitability. The Centre should join hands with Punjab and Haryana governments and double this incentive to at least Rs 35,000/ha, and this should be assured for at least five years. This would not result in any extra financial burden, as the Centre will save on the fertiliser subsidy and states on power subsidies. Assured procurement of pulses and oilseeds from these states at minimum support prices would also help farmers in reducing market risk, which in turn will help in reducing imports of pulses and edible oils.

The second key action is to expedite implementation of Delhi’s electric vehicle (EV) policy. It aims for 25% of all new vehicle registrations to be EVs by 2024, now extended to March 2025, pending the launch of the EV 2.0 policy. Besides the high upfront cost of EVs, a shortage of charging points has constrained their uptake. While the Delhi government plans to establish at least 30,000 charging points across the city, current data from the Switch Delhi website shows only 1,919 charging stations, 2,452 charging points, and 232 battery swapping stations. It should be mandatory for parking areas in residential colonies, offices, and malls to include EV charging points.

The third policy action is to introduce innovative technologies to capture air pollutants, such as installing vacuum cleaning towers at major traffic crossings and in areas with high pollution levels. In fact, it won’t be a bad idea if the Aam Aadmi Party government in Delhi changes its party symbol from the jhadu (broom) to a vacuum cleaning tower!

With a mix of policies, technology, and economics, Delhi can win the battle against air pollution, and then it can be extended to other cities in the Himalayan shade. It is a matter of sheer survival.

Views are personal

The authors are distinguished professor and senior fellow at ICRIER, respectively.