By Harsh Wardhan

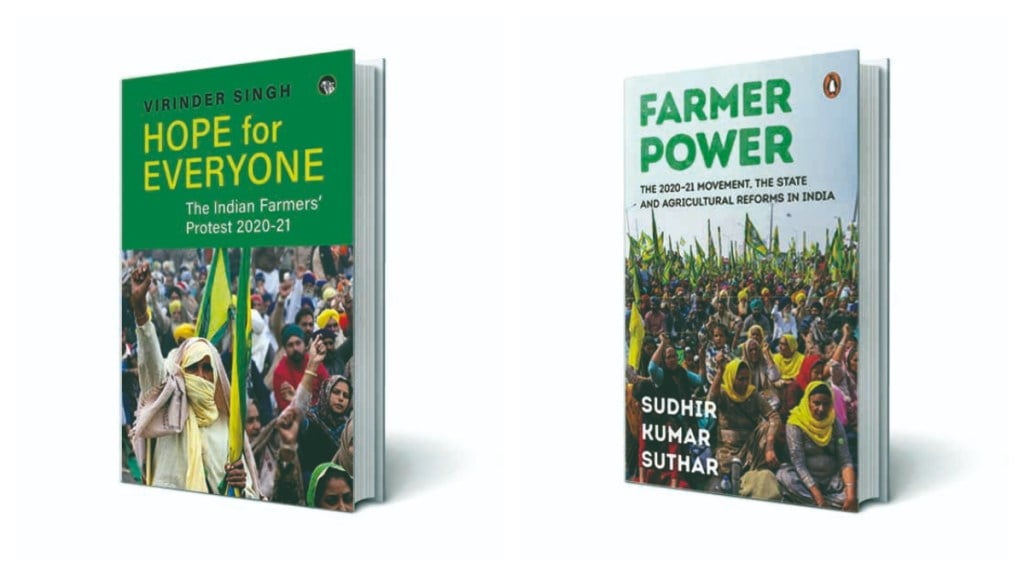

The 2020-21 farmers’ protest against three farm laws has already been widely discussed in public and academic circles, but book-length studies are still few. Sudhir Kumar Suthar’s Farmer Power and Virinder Singh Kalra’s Hope for Everyone, published within months of each other, are among the earliest comprehensive accounts of this landmark movement. Both focus on the encampments at Delhi’s borders and read the agitation as far more than a dispute over farm laws, approaching it from distinct disciplinary standpoint. Together, they offer a rich and complementary understanding of the protest, while also revealing gaps that invite further economic and policy analysis.

Both books begin with the premise that the 2020-21 protest was one of the most significant mass mobilisations in contemporary India and must be placed at the centre of discussions on democracy, state-society relations, and agrarian change. Suthar, a political scientist at Jawaharlal Nehru University, frames the movement as ‘farmer power’, built over a decade-long buildup of resistance that culminated in a year-long encirclement of Delhi by approximately 300,000 farmers.

In doing so, he challenges established views of Indian peasants as politically passive and questions post-1991 market-led reform thinking. Kalra, a sociologist known for his work on Punjabi culture, views the protest as a collective experiment in hope, dignity, and solidarity, in which farmers, labourers, women, and Dalits opened up ‘a space of hope’ against authoritarian capitalism at the very borders of the national capital.

Chronologically, the narratives overlap substantially. Both trace the movement from early opposition to the farm ordinances in Punjab, through the consolidation of multiple unions into the Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM), the march towards Delhi, the establishment of camps along national highways, the Republic Day events of 2021, prolonged negotiations with the government and the eventual repeal of the laws in November 2021. Both authors emphasise the symbolic importance of occupying highways rather than traditional protest sites, like Jantar Mantar or Ramlila Maidan.

These spaces became centres of debate, care and community living, rather than mere sites of blockade. Both authors also reject the claim that the protest was limited to Punjab or dominated solely by large farmers, even while acknowledging regional and social hierarchies within the movement. Beyond this shared ground, however, the books diverge in approach and emphasis.

Farmer Power is primarily a political analysis of the movement. Suthar carefully reconstructs the policy background to the farm laws, tracing debates on agricultural marketing from the late 1990s through various government committees (Guru, Swaminathan, Doubling Farmers’ Income). He shows how decades of gradual reform discussions were replaced by the sudden introduction of three central ordinances during the pandemic. Even if the laws had some economic rationale, Suthar argues that the manner in which they were introduced, with limited parliamentary debate and weak consultation with states, made them politically untenable.

A central concept in Suthar’s analysis is ‘hybridity’. He uses it to explain how the movement brought together diverse interests and forms of organisation. The protest brought together large and small farmers, agricultural labourers, unions, and civil society groups, social media and traditional village networks, rural cultural forms and contemporary music. This hybridity, Suthar argues, helped sustain a largely non-violent movement over a long period despite pressure from a powerful central government.

Kalra’s Hope for Everyone takes a very different route. His focus is less on policy architecture and more on lived experience. Drawing on fieldwork, interviews, songs, posters, WhatsApp messages and everyday conversations, he brings the protest camps to life. As one reads the book, vivid images emerge of langars, makeshift libraries, tractor-trolleys turned into homes, and protest stages filled with speeches and music. The background stories, interviews, incidents and cultural expressions unfold so clearly that the book often feels like a ready script for a documentary series.

Kalra pays particular attention to voices that are often marginal in political accounts: women, Dalits, migrant workers and landless labourers. He introduces the idea of ‘Kisanistan’, not only as a geographical protest zone across Punjab, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and neighbouring regions, but as a broader reimagining of who counts as a kisan. His key idea is hope, understood not as an abstract emotion but something sustained through shared work, rituals and storytelling under uncertainty, challenging any simple image of a uniform farmer movement.

In terms of structure, Farmer Power is more conventionally academic and policy-focused. After an introduction that places the movement alongside some global protests, it moves through chapters on the making of resistance, the ‘controversial laws’, the Delhi morcha, resurgence, policy debates, repeal, and an uncertain post-repeal future, including ‘Farmer Protest 2.0’. The chapters on policy debates and committees are particularly useful for contextual understanding.

Hope for Everyone is less linear and more reflective. While it broadly follows the movement’s timeline, chapters often move back and forth between narrative, reflection and cultural analysis. It offers fewer institutional details but much richer accounts of everyday life at Singhu, Tikri and Ghazipur. From an economist’s viewpoint, both books are strong in capturing the democratic and ethical dimensions of the protest, but less comprehensive on the economics of reform.

On the three farm laws, both authors emphasise how they were perceived by farmers: as signalling withdrawal of the state from agricultural markets, weakening APMC mandis that function not only as trading platforms but also as social institutions, empowering large corporate players, and increasing fears of land insecurity through contract farming. The role of arhtiyas within the APMC system is treated largely with sympathy, as part of a larger rural ecosystem.

What is largely missing, however, is a discussion of successful contract farming experiences within India, particularly in sectors such as horticulture and poultry. The books also do not acknowledge that dairy, India’s largest agricultural commodity, operates almost entirely outside the APMC and MSP framework, yet has achieved sustained growth through a combination of cooperative and private models. Similarly, the relatively successful functioning of private mandis in several states receives little attention. Suthar documents fears that mandis would decline once private markets were allowed without adequate safeguards, and that contract farming could gradually undermine land ownership. Kalra, in turn, vividly shows how these concerns shaped everyday conversations and mobilisation, especially among small and medium farmers.

Yet neither book systematically explores the counter argument that wider marketing options, well-designed contract arrangements with clear protections, and private investment in storage and processing could, in principle, improve farmer choice, reduce post-harvest losses and modernise supply chains, provided a strong regulatory framework is in place. From this perspective, the government’s failure lay as much in poor timing, weak consultation and lack of trust building as in the idea of market reform itself. Although Suthar notes that earlier committees had envisaged mixed models with roles for both the state and private players, he largely interprets the laws as corporate oriented, while Kalra remains more concerned with how people resisted the reforms than with designing alternatives.

A similar pattern appears in the discussion on minimum support price. Both books clearly present the movement’s demand for legal backing to MSP as a claim for economic security and justice. However, the structural limits of MSP receive limited scrutiny. Its concentration in a few crops and regions, the small proportion of farmers who actually benefit from it, and the exclusion of entire subsectors such as poultry, dairy and fisheries are only briefly addressed. Neither book fully engages with the fiscal, logistical and trade implications, as well as alternative designs, which receive limited attention.

These gaps do not weaken the books’ core arguments, but point to the need for interdisciplinary work linking democratic claims with workable reform pathways. Read together, Farmer Power and Hope for Everyone offer an important early record of the farmers’ movement. One provides a political and institutional view, the other an account of everyday life and culture. Together, they show that the 2020-21 protest was about more than repealing three laws. It was about reclaiming democratic voice, turning highways into political spaces, and bringing agrarian concerns back to the centre of public debate.

In that sense, these books are best read not as final verdicts, but as foundations for a larger conversation on agriculture, democracy and the future of rural India.