By Faizal Khan

Two decades ago a group of widows of farmers in Wayanad, Kerala, who killed themselves unable to bear the burden of mounting bank loans and losses, sat in protest in a tiny tent at Jantar Mantar in the national capital. Soon Arundhati Roy arrived to squat down with them. Calling each sad-looking, sari-clad woman chechi—sister in Malayalam—the Booker Prize-winning author spoke with them in a courteous, soft voice. Before she left, Roy pressed wads of crisp Rs 500 notes in their hands. The fleeting moment reflected sharing, of both money and sorrow. It was an act the famous author used to perform inpenury and plentifulness, as we learn from her just-published memoir.

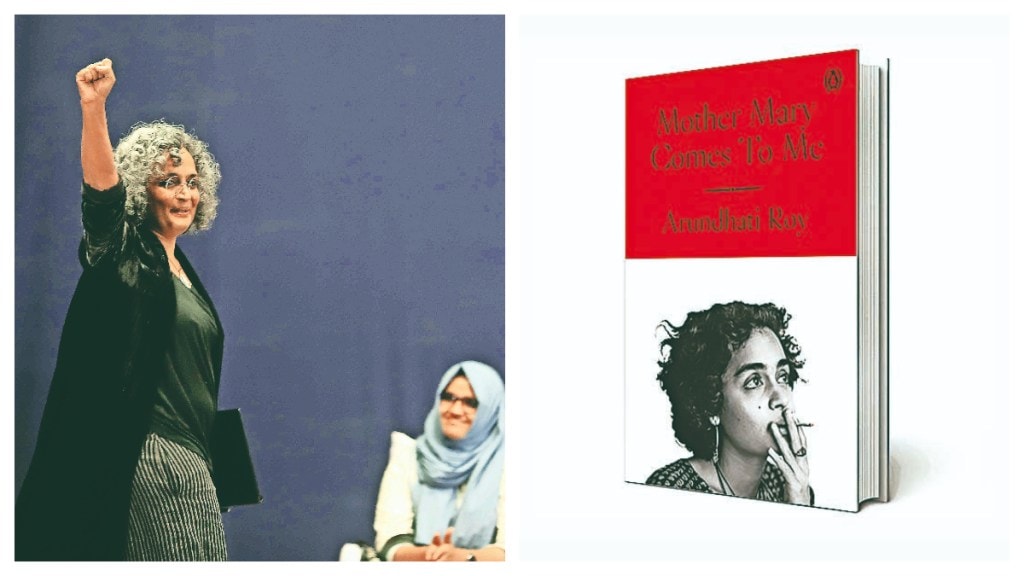

While sharing money with the widows of Wayanad is not part of the memoir, Mother Mary Comes To Me, Roy reveals how land and wealth, for her mother Mary Roy and herself, were something for the “greater common good”, just like Ayememen’s Meenachil river in The God of Small Things or Anjum’s Jannat Guest House in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Roy is rich. She also has a lot to say about being rich, like sharing the Booker Prize money and royalties with family and friends and creating a trust that gives money to filmmakers and artists for new projects.

Meanwhile, Mary Roy would expand her wealth to spread knowledge to school children and give scholarships to orphans. In a country where the top 10% own more than two-thirds of the total wealth and the bottom 50% hold fewer than 7%, Roy and her mother’s ways of dealing with wealth clash with the current unequal distribution that further widens the rich-poor gap.

Not even a big dam can hold back the flow of memories of Roy. The memoir carries the currents of the rivers and its people that she has backed. Based mainly on a rocky relationship she shared with her famous mother, a towering single parent of two children whose strange ideas radicalised school education in their native town of Kottayam, and who single-handedly took on the Syrian Christian church and community and her family by challenging the Travancore Christian Succession Act to demand equal rights for Christian women in their family inheritance, the book is also about equally testy times between the author and her motherland. Even as it is about the past, the book, like all of her previous works, exudes a now familiar air of contemporariness, which is at once striking and scary.

Roy’s first book after the 2020 non-fiction, Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction, the memoir traverses a long journey, both in time and geography. The book begins nearly six decades ago and ends with her mother’s passing in September 2023. Roy was almost three and her brother a year-and-a-half older when their mother walked out on her alcoholic husband, a tea estate manager in Assam. Mary Roy had no money and possessions. The following years of living as ‘fugitives’ under someone else’s roofs as the author writes, would turn out to be the first rounds of creative spirit for the mother and her children.

Assam would be followed by Kolkata; Ooty in Tamil Nadu where Mary Roy’s late father had a house; Ayemenem in Kottayam district of Kerala where the mother would set up a non-traditional school; Delhi where Roy would later arrive as a 16-year-old student of architecture; Italy for a residency in urban architecture; Pachmarhi in Madhya Pradesh where she would become an actor without dialogue in the critically-acclaimed film Massey Sahib; London the scene of the Booker Prize for The God of Small Things in 1997; a day in Tihar jail as an inmate, and even the forests of Chhattisgarh where she would walk with the Maoists.

A literal conversation between Roy and her mother, the book hits an emotional and philosophical path, more so because of the centrality of the book, an exacting relationship between the two. It, however, unravels a wider world of friendship (humans and non-humans included), creative labour, and long-lasting bonds with famous writers, actors and house helps who shaped the author’s life and character. In the 372-page memoir written in her characteristic sharp tone and passionate narrative, Roy links the past and the present in an unbridled web of contemporariness. The author winds up her life’s ups and downs in an expansive canvas of literary odyssey, revealing her mother’s powerful influence on her, which more than often transcended into a punishing routine of shouts and shrieks.

“Quite often I found myself wishing I were her student and not her daughter,” she writes. The book, however, is as much about a punishing parent as it is about a polarising politics in the country today. Roy was a child who arrived in the world, as she reveals, against her mother’s wishes to get rid of the unborn child. Childhood wasn’t easy for Roy and her brother. In between searching for a new roof over their heads and her debilitating asthma attacks, Mary Roy abandoned affection for astuteness. In Ooty, Mary Roy would find the first sparks of her life’s mission in imparting learning for children as a school teacher. At the same time she encouraged her daughter to write. And she wrote: “I hate Miss Mitten…” about an Australian missionary and her teacher. Mary Roy would preserve the notebook with the writing. Roy was still a toddler when her grandmother and uncle threw the Travancore Christian Succession Act at her mother to evict them from their home in Ooty. Many years later the Supreme Court would strike down the same Act based on a petition filed by Mary Roy.

Life in Ooty was followed by life in Ayemenem, a village on the banks of the Meenachil river in Kottayam district of Kerala where its water, worms and fish would form an eternal bond with the young Roy. The characters from nature are complemented by an array of mostly relations, many of whom are part of The God of Small Things. Roy’s maternal grandfather was an imperial entomologist and an abusive husband who ended the dreams of his wife, an aspiring concert-class violinist, by smashing her violin. G Isaac, her mother’s brother, was one of India’s first Rhodes scholars and a Marxist “with a keen interest in inheritance and private property” and the owner of a pickle factory. Isaac, one of Roy’s favourite relations, would go on to lose all that property after the Supreme Court judgment on the Travancore Christian Succession Act, and the author would help him tide over the crisis.

The painstaking birth and build-up of Mary Roy’s famous school in Kottayam mirrors her daughter’s slow and moneyless initial years in Delhi at the SPA and later, a period that sets the stage for Roy’s literary turn. She bids her own time to develop the “architecture of language” which leads to the debut novel. While visiting her barsati in Delhi, Mary Roy brings her an old typewriter that would churn out pages of Roy’s film scripts like the 1989 English language In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones, which won the author a National Film Award. “She could break my heart and mend it too,” Roy says.

British critic Derek Malcolm, who watched the movie, suggested a new name for the movie because, according to him, it wasn’t English. For her first novel, Roy wanted to try to “write the opposite of a screenplay”. “A stubbornly visual but unfilmable book”. The author would, in the meantime, meet her father for the first time after Mary Roy left Assam, in a hotel in Paharganj. The father is a cricket fan, a fan of Australian cricket to be precise, a love that would make him anti-national today, Roy adds.

The past is like a river, if she hasn’t been captured and wound up inside a concrete monstrosity to make our lives better than before. The river runs away with everything from before, the currents carrying the weight of memories downstream to confront the present. Roy’s new non-fiction swoops down the pages like all of that came before, blurring the boundary between reality and fiction. The magic-frilled edges of memories from childhood meet the crudest contemporary reality, making it impossible to detach from both.