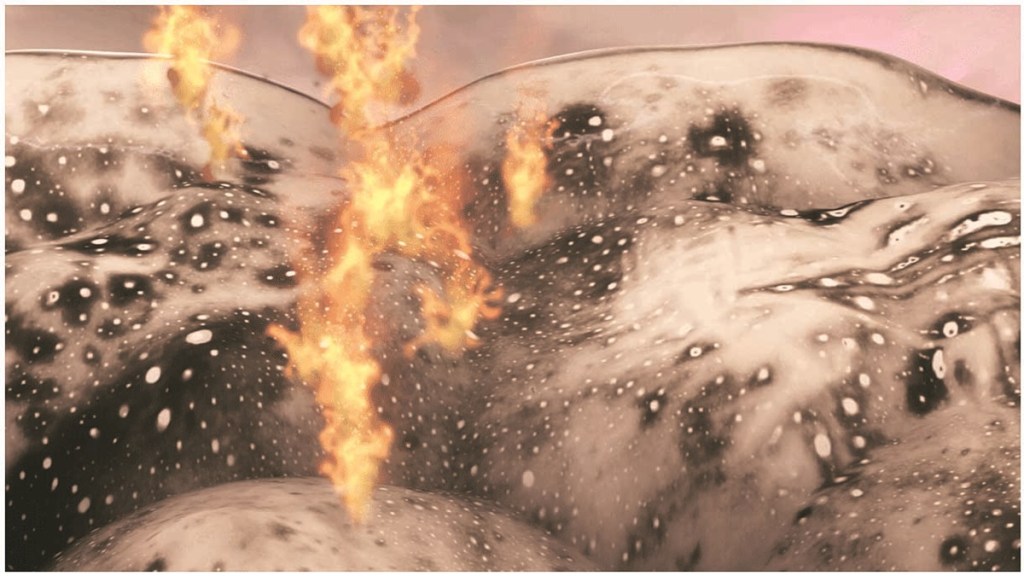

The screen is small, set in a dark wall, showing black and white digital granulated waves that look like undulating sand. You step closer, standing on the prescribed line, and peer at the screen trying to fathom the art work. Then, suddenly flames burst on the screen. As you look at the other side, the fires follow your gaze. Childlike, you shift your gaze frantically, and the screen responds with the same intensity. It’s as if the viewer is creating the art work.

In another room, the audience is actually creating art. Visuals and colours appear on a screen that are a real-time representation of the neural waves of a viewer being mapped by a sensor. Simply put, what you think, takes the form of art.

As Rahaab Allana, co-curator of Terra Nullis, a project by six French artists at the recent Serendipity Festival, says, “The power shifts to the viewer, who has agency, who has power, where the audience becomes the artist in a way. You could call it democratic art!”

But digital is a double-edged sword. If it gives you power, it also takes over control. Like millions of images taken by humans being re-interpreted by artificial intelligence, which morphs two or more photographic images and creates something new altogether. Even as it works from a finite database, the results are infinite, the possibilities endless. Titled Completion, the attempt by artist Gregory Chatonsky is to visualise a post-human world, a kind of archive of the lives we lived. But where does the human realm end, and where does the machine assert itself?

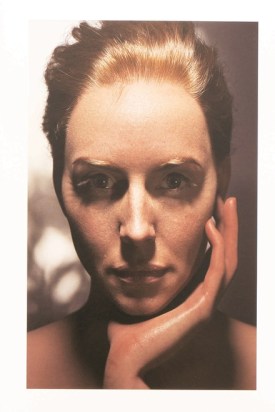

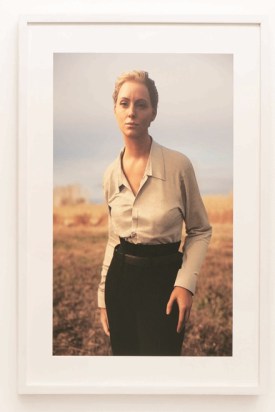

Like a mysterious woman staring at you from numerous photographs on the walls, standing amid fields, looking back from the bed on which she lays nude, or just locking eyes with you with her beautiful face cupped in her hands. You are drawn to her, trying to decipher her enigmatic stare, attempting to read her eyes. Then you shift your attention to a screen on the side of the room, where the making of Isis is explained in detail. Isis, ancient Egyptian goddess who has the power to destroy and create worlds, finds reincarnation in a computer generated imagery, lifelike in the various photographs scattered across the room in an artwork by French artists Simon Brodbeck and Lucie de Barbuat.

This is aptly Terra Nullis—no man’s land—the digital world we live in, belonging to no one, and yet belonging to everyone. The inherent query is of human dominance over nature, man’s control over the planet, space and everything beyond. Flora or fauna which took life, existed and sustained over various physical parts of Earth, now finds itself at the mercy of humans as they conquer the planet as they please.

Machines, too, could be doing the same to humans, dominating, snatching control, making them redundant. As we all are posed with a plethora of virtual choices, existing in an addictive cyber universe, the answer to the eternal question of the present—are we all digital captives?—finds myriad answers, and perhaps none. For the present, we seek solace in Terra Digitalis.

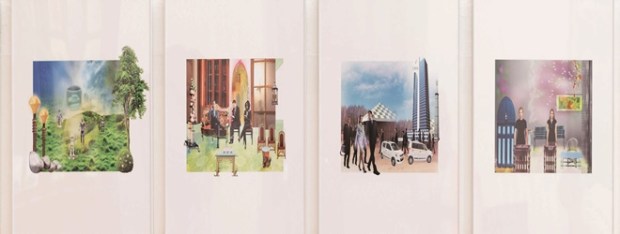

The black box of Uber

In computing it’s called a black box, a system whose functions are known but internal working is a mystery. So when artist Tara Kelton asked some Uber drivers how they thought Uber operated, the drivers—most of them strangers to the machinations of a virtual world—came up with vivid imaginations. The descriptions then took the shape of images created by a photo and design studio, depicting the incongruity between reality and imagination, where the drivers are managed by an algorithm and not real people. These art works were on display at the Serendipity Arts Festival held in Goa recently.