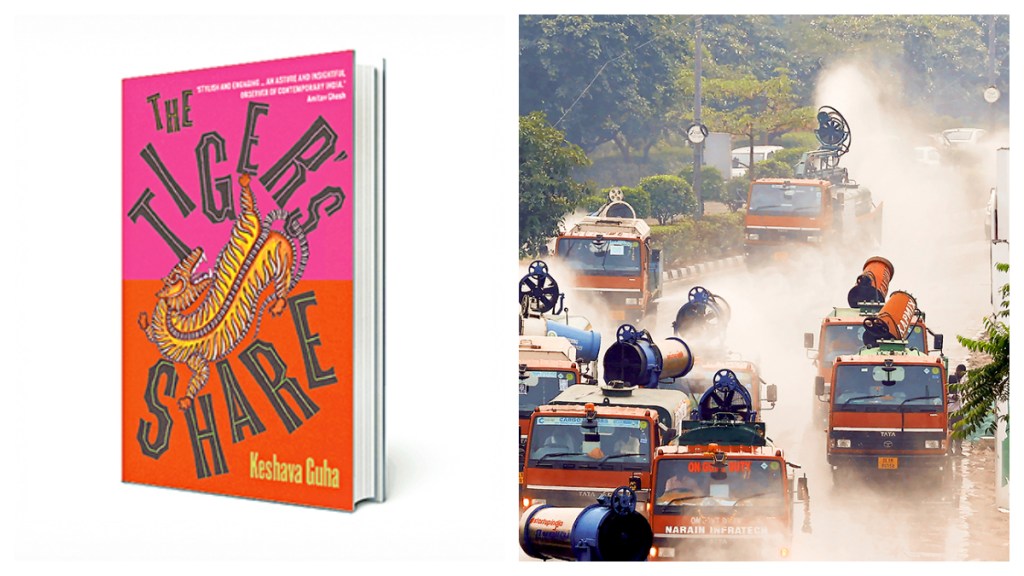

The suffocating air pollution in Delhi has found its way into literature and popular culture in more ways than one. In her 2017 book, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Arundhati Roy, a Delhi resident and Booker Prize-winning author, chastised her fellow-residents for romanticising about the pollution while social, moral and political decay abounds around them. In his second novel, Keshava Guha goes further. In The Tiger’s Share, which follows his debut novel, Accidental Magic, six years ago, Guha wraps a wreath of melancholy around the pervasiveness of pollution in the national capital.

The befouling air of the capital runs across The Tiger’s Share as a metaphor for the ills of its all-encompassing wealth. Set in Delhi, the novel tells the story of the rich and the powerful, whose every breath is a push for more money and power. Narrated by a lawyer who is worried about the growing morass around her, it offers a rare view from the inside. A tale of two families facing internal feuds in south Delhi, the stark symbol of the gaping divide between the rich and the poor in the country, The Tiger’s Share runs a scalpel through the guts of a decaying city.

Story of wealth and decay

Guha’s canvas is short and narrow in The Tiger’s Share in line with the arithmetic of wealth accumulated by a few. The novel focuses on two families, one that lies low in the scheme of things and the other entombed sky high. The first is a family that lives in Hauz Khas, an upscale residential area. The second is a family in Golf Links, vastly prosperous and lying in close proximity to the political power of Lutyens’ Delhi. Tara Saxena, the narrator, is a member of the Hauz Khas family and lives independently from her parents.

The novel sets off with an invitation to a family meeting called by Tara’s father. The meeting will also be attended by her brother, Rohit, an aspiring filmmaker who flies in from New York where he lives after stints of studies in universities across the Atlantic. Brahm Saxena, the father who owns five properties in the city, shocks the family with his decision to relieve his children of any expectations of inheritance. Thus begins a cat-and-mouse game of want that defies the laws of inheritance.

Tara, whose degrees of materialistic instincts most often dilute in a glass of alcohol alone in the balcony of her two-bedroom apartment after court work, an upgrade from an earlier barsati, watches with growing anxiety as Rohit begins his own schemes of passage from parental abandonment. The schemes involve a war cry on the world wide web for human ‘thrival’ instead of survival. Tara soon rekindles a forgotten friendship with Lila, also like her, the eldest of her family that lives in Golf Links. Lila, it turns out, wants legal help in thwarting her brother Kunal’s attempts to oust her after their father’s death. The friendship of convenience widens the scope of the novel’s characters from sulking siblings to scheming sisters. It is a sisterhood against an alliance of marauding brothers.

Biting social commentary

The brevity of Guha’s characters is offset by the constant babbling of a city as it works day and night to enrich a certain few. Most of the action takes place in the vicinity of a Sundar Nagar or a Jor Bagh or in a vaunted cafe. But the readers are awakened to the city’s reality with scenes in a metro or near a garbage fill. Guha throws in such terms as ‘rent-free cough’ and ‘mellow murderousness’ to satirise the city’s air pollution. The infamous landfill of Ghazipur, therefore, is bemoaned as an ‘architectural achievement’.

The Tiger’s Share straddles a world between pollution and poverty and predominance and powerlessness while questioning the ever-skewed gender equations increasingly advanced by the social and political interests of a patriarchal society. The novel steers clear of party politics most of the time, though there are subtle hints like the renaming of Aurangzeb Road as APJ Abdul Kalam Road, “after the government’s notion of a good Muslim”.

The hints sometimes become louder as some characters, who have lived abroad but chosen to return, trumpets their patriotism. In Guha’s ‘anti-city’, it becomes slowly visible in the smog of inequalities and injustices that pollution is the least of its problems. Guha’s unabashed portrait of south Delhi’s internecine family feuds dictates an impish patter from its protagonists, which he delivers with a biting insouciance.

Faizal Khan is a freelancer