The declining number of students at a government-aided school on Mandir Marg in central Delhi is a telltale sign of the state of the country’s education space today. As many as 85 students after the 2023 academic session, and 90 students after the 2024 session, took their transfer certificates and left the century-old institution that used to have an average of 1,300 students in each batch, compared to about a thousand at the moment.

Incidentally, almost 200 of these students, who left the school in the past two years, haven’t done so out of choice, but out of compulsion, as per the principal, the constraint being parents unable to make ends meet in the city, and having to move back to their villages with the kids.

These numbers are in line with what the Unified District Information System for Education (UDISE+) reports, recently released by the Union ministry of education for 2022-23 and 2023-24, also reveal. The reports show that school enrollments (in government, government-aided, private, and other institutions) fell from over 260 million in 2021-22 to 251.7 million in 2022-23 and then to 248 million in 2023-24—a sharp decline of over 10 million students in merely two years.

Interestingly, the report says that one of the possible reasons for this decline in enrollments could be that now the government uses more efficient methods of data collection and Aadhaar verification, which prevent duplication of records. The other possible reason was that post Covid-19, many families who were forced to take their kids out of private schools could afford to send them back, leading to a decline in government school enrollments.

Dropping out

However, when FE looked closely at both of these arguments, there were clear lags.

Prachi Kumar* (name changed on request), the principal of the government-aided school on Mandir Marg, explains, “In the past 3-4 years, the families of many of our students have moved back to villages because they’re unable to make ends meet in the city, which is why we’ve been seeing a lot of dropouts. Students who came from far-off areas also can’t afford buses or public transportation; so they’ve enrolled in schools closer to their homes, adding to our decreasing number of students.”

On the other hand, Furqan Qamar, education expert and former adviser (education) to the Planning Commission of India, feels that the increasing dropout rates and decreasing enrollments have more to them than meets the eye. Qamar says, “I studied these numbers and found that they are linked to the population of the relevant age group and the fertility rate declining. This is a demographic shift.”

Qamar explains that since 2014-15, the school-going population, that is children aged 6-17 years, have declined by 17.3 million. In fact, according to the latest National Family Health Survey-5 (conducted between 2019 and 2021), India’s total fertility rate stands at 2.0 (or two births per woman), which is below the replacement rate—or “the level of fertility at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next”, as per a study published in PubMed Central.

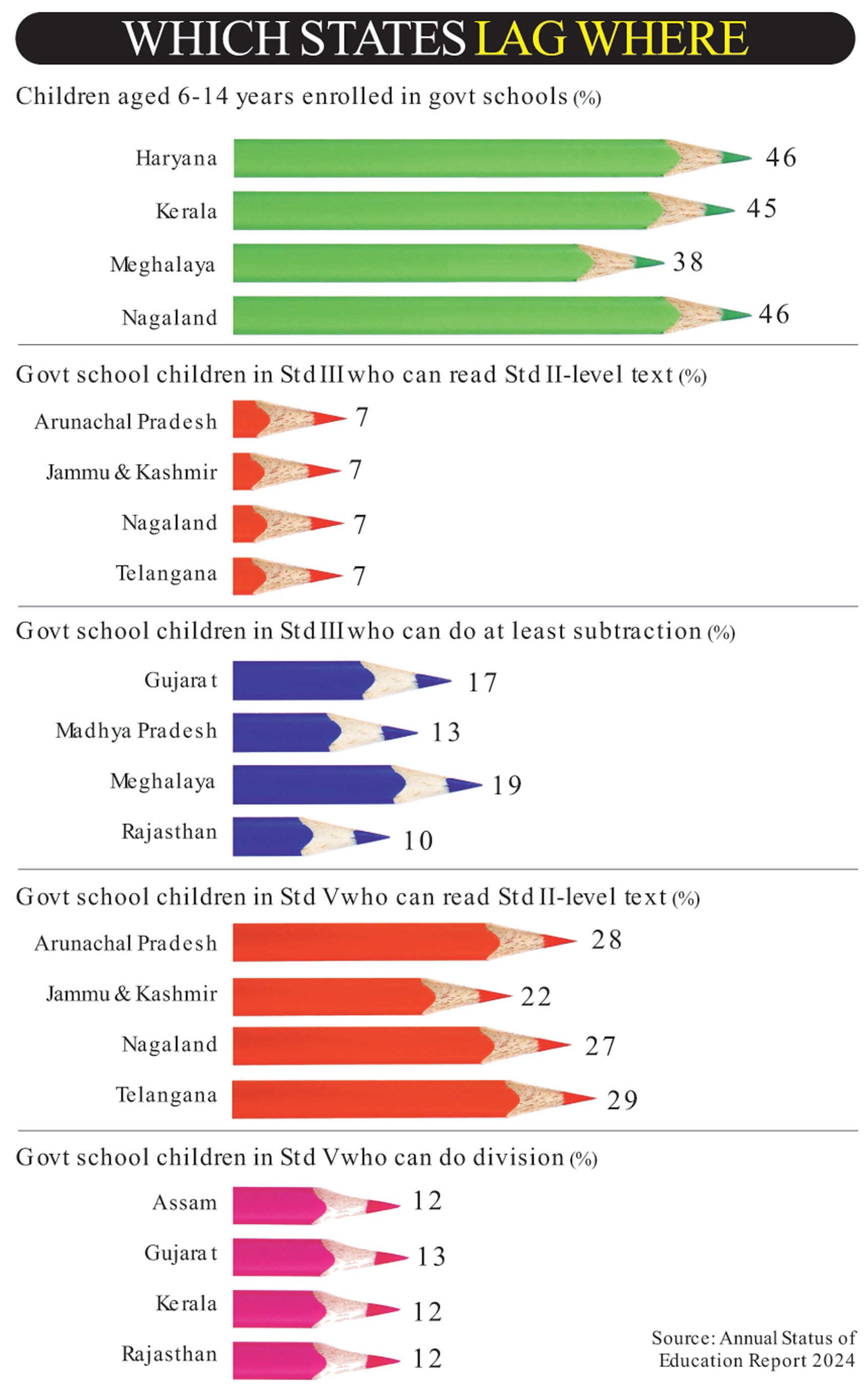

What is noteworthy is that the Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2024 or ASER, released on January 28 by Pratham NGO—which surveyed 6,49,491 children across 605 rural districts and 17,997 villages—also notes that for children in the age group of 6-14 years, government school enrollments had dropped from 72.9% in 2022 to 66.8% in 2024. For 15-16-year-old children, the percentage for students not enrolled in any school stood at 7.9%, and the proportion of girls not enrolled in any school was 8.1%.

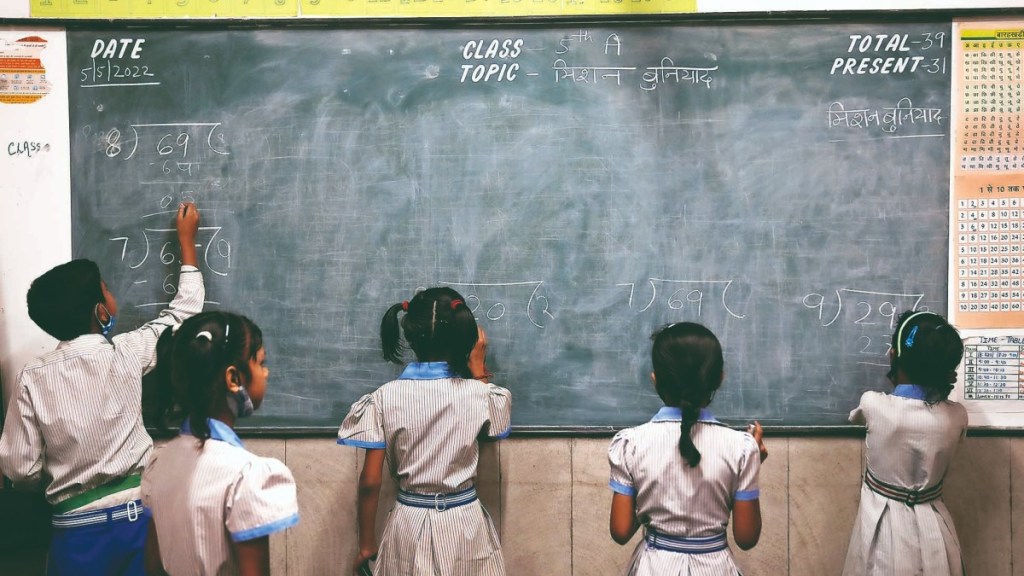

Incidentally, there was quite an increase in government primary schools with less than 60 students enrolled—from 44% in 2022 to 52.1% in 2024. On the other hand, ASER adds, “Two-thirds of Class 1 and 2 rooms in primary schools are multigrade, with students from more than one grade sitting together.” However, if you ask teachers in government schools about the fall in enrollments, the answer that comes is unanimous— government schools have a bad reputation.

Barely 70 km from the national capital, in a primary school in Meerut’s Kharkhauda village, Anjali* (name changed on request), a teacher, tells FE that the reason for the drop in enrollment rates is private schools. “Many parents in our village think students do well in private schools. They believe that since they are paying Rs 200-250 in fees (as opposed to free education in government schools), the child will be paid more attention to,” she adds.

Smita* (name changed), another teacher from a government school in Meerut’s Bijoli village, agrees: “During Covid, a lot of private schools had shut down. Now that these are reopening, parents are pulling their kids out of government schools to send them to private institutions. It’s not the parents’ fault either, they want to do the best for their children and they think private schools are better.”

Interrupted studies

But like we said, there’s more to these reports than meets the eye.

It’s not just the number of students in schools that has a big question mark on it, but these reports have also brought into question the quality of education being imparted in government schools.

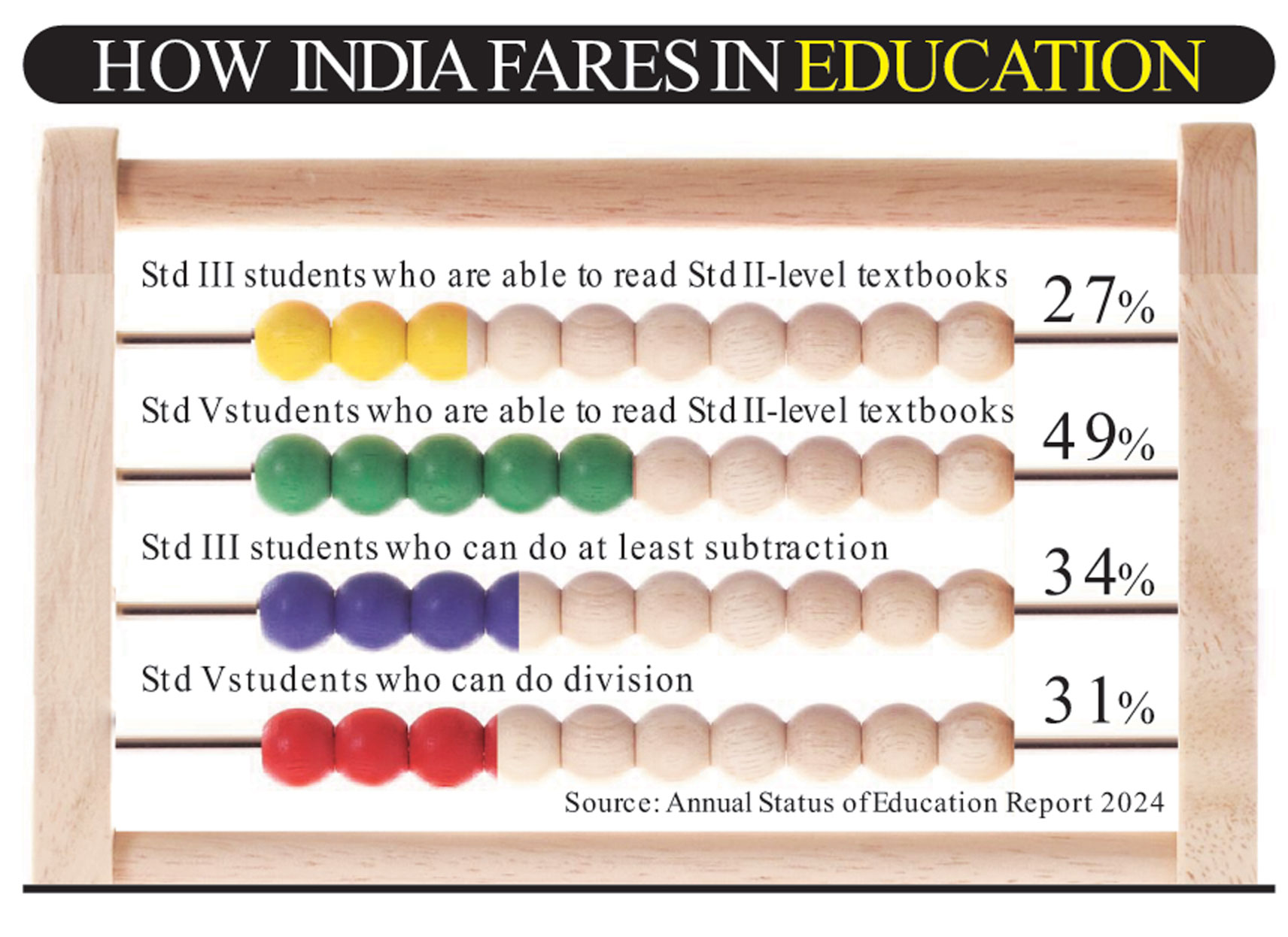

ASER reveals:

- 23.4% students in Class 3 and 44.8% Class 5 government school students were able to read Class 2-level text

- 27.6% government school students in Class 3 were able to do numerical subtraction problems

- 30.7% government school students studying in Class 5 could do numerical division problems.

Wilima Wadhwa, director of ASER Centre, tells FE, “The pandemic-induced school closures of almost two years led to significant learning losses in reading and arithmetic skills. There has been an almost full recovery in reading for both standard 3 and standard 5. In arithmetic, we are seeing more than a recovery for both standards 3 and 5, with arithmetic levels in both grades surpassing those from a decade ago.”

This, says Qamar, is an extremely positive sign. However, it’s still noteworthy that even while this is an improvement from previous years, the numbers are still pretty abysmal when it comes to the ability of students in Class 3 and 5 to read and do basic arithmetic problems.

Interestingly, all the teachers said that they are constantly overburdened, which means that sometimes their primary job of teaching and imparting education has to take a backseat.

The UDISE+ report had revealed that in 2023-24, there were 9.8 million teachers in the country; and over 110,000 schools in the country only had one teacher. This is when the total number of school students in the country was 248 million in the same year, according to UDISE+.

Prachi, from the government-aided school in Delhi, says, “Our school has a shortage of teachers— we only have 37 permanent teachers, and 23 others hired on an ad hoc basis. But we have a barrage of duties. Our school is a CBSE centre, departments like Veer Gatha and Pariksha pe Charcha have entered government schools, we are involved with duties related to the Post and Telegraph department. For the first time in the recent Delhi elections, teachers from government-aided schools were also put on duty. This does affect the amount of attention we are able to give to the classroom and the curriculum.”

“At the district level, we are rostered as booth-level officers and are made part of the household surveys too. It disturbs the students’ studies but we try to finish coursework despite it all,” Smita from the Bijoli school says.

In Noida Sector 12’s Adarsh Government Primary School, a teacher says, “Shortage of teachers is a problem for sure, but what’s causing more disruption is that the teachers we do have are rostered for too many out-of-school activities. At the moment, three of our Class 8 teachers are on board exam duty in another school. So the students’ classes have been hampered.”

True to what the teacher said, when FE visited the school, all sections of Class 8 were empty, with students roaming around in the sports field.

Another problem is that there are too few teachers for too many students. At the Rajkiya Government Inter College in Sector 12, a teacher says, “We sometimes have more than 70 students in each class. It gets difficult to focus on all of them.”

The Adarsh school teacher agrees. At her school, classes have anywhere between 50 and 80 students, and teachers find it difficult to cater to all of them. “It ultimately falls on the students to pull themselves up and be focused on studies,” says the teacher.

However, both the teachers from Meerut district say that since the National Initiative for Proficiency in Reading with Understanding and Numeracy (NIPUN) Bharat Mission was launched in 2021, there has been an increased focus on foundational learning.

Wadhwa agrees with this as well. Says she, “The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, for the first time, set systemic goals for universal foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) in the early grades under the NIPUN Bharat initiative.”

(Infra)structural issues

But wait, there’s more. A huge gap also exists in our infrastructure. The UDISE+ report had found that only 57.2% schools in India had functional computers, 53.9% had internet access, and only 52.3% schools had ramps that made them accessible to people with physical disabilities.

A much talked about aspect of school infrastructure has also been about usable toilets. Over the years, reports had shown that many girls after hitting puberty had to drop out of school because of a lack of usable separate washrooms. This has thankfully changed. ASER data says, “The fraction of schools with usable girls’ toilets increased from 66.4% in 2018 to 68.4% in 2022 to 72% in 2024.”

However, hygiene still remains a problem. When FE visited the Government Primary School in Noida’s Nithari, we were met with a huge pile of garbage lying in the middle of the school field. Even walking past the students’ washrooms was a telling tale, with a stink all around.

The school students, during their lunch break, also were interacting with vendors outside through a small empty space in the gate, while there was dust and waste right next to them.

In the Rajkiya school in Noida, though, there’s another reason girls might be dropping out—safety. A school staffer reveals: “This school is not the best for girls. The boys are hooligans and safety is a big issue. If you want to get some girls enrolled, you should go to another school.”

Teachers at the Adarsh school, which is barely 600 metres away from Rajkiya, dismiss this almost as a non-concern. “Boys in Classes 7-8 behave however they want to. There’s not much we can do except recommend a girls’ inter-college to those concerned about safety.”

Going forward

Too many problems, not enough solutions. Where do we go from here?

For Qamar, the only way to ensure that quality education is imparted to students is by making certain that government schools don’t just have qualified teachers, but teachers who can be available for students—not burdened by a thousand other things.

When it comes to private schools, the way to go ahead is focusing on parents and students alike. Qamar explains, “A majority of students who are first-generation learners go to inadequate private schools. The students here are highly dependent on their teachers for all forms of learning because they do not have that kind of support back home—parents who can guide them in studies.

The solution there is helping fill the deficit that students might be facing in terms of family support.” Fortunately in this case, ASER found that the percentage of mothers of children aged between 5 and 16 years who have never attended school saw a sharp decrease from 46.6% in 2016 to 29.4% in 2024, showing that 19.5% women had studied beyond Class 10 in 2024. Even the percentage of fathers of students in the same age group who have studied beyond Class 10 grew from 17.4% in 2016 to 25% in 2024—indicating a culture of education percolating to the roots.

Ameeta Mulla Wattal, chairperson and executive director of education, innovations, and training, DLF Foundation Schools and scholarship programmes, shares that while reports like UDISE+ and ASER bring out important learnings in our education landscape, it is critical to look at these surveys at a micro-level too. She explains that each time these reports come out, educators should look within their own institutions and see where changes can be made. Of course, they would need the help of progressive policy makers to help prioritise goals.

“Formative years are extremely important for any student. This is where we need to fill in gaps in gender parity and digital literacy, so that it doesn’t lead to a lack-of-skills problem in young adults. What we need to ensure is that we create more platforms for learning, and that we keep them accessible,” she adds. Wadhwa adds, “Changes of this magnitude at the all-India level have not been observed before. It is crucial to maintain this momentum to ensure continued progress.”

Meanwhile, email queries to the secretary, ministry of education, and the CBSE remained unanswered till the time of publishing this story.