For distributors of the country’s largest consumer goods company, Hindustan Unilever (HUL), 2024 has started on a disappointing note. The fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) giant has restructured the distribution margins with the fixed margin having been reduced by 0.6% to 3.3% in urban areas and the variable pay increased by 1.3% to 2%. This has irked general trade. In rural areas, the fall in fixed margins has been even sharper from 5% to 3.6%, a drop of 1.4%, say distributors, while the variable pay has surged by 0.4% to 1.7%.

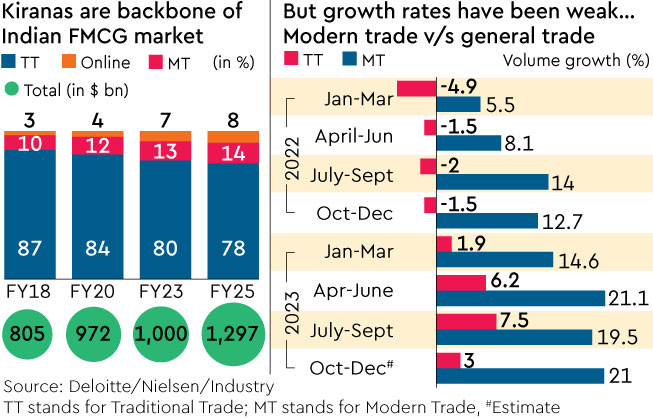

The changes come at a difficult time for general or traditional traders, considered to be the backbone of the country’s Rs 5-trillion domestic FMCG market. More than three-fourths or roughly 80% of an FMCG company’s sales come from general or traditional trade. However, a rural slowdown has put this channel under a lot of stress. Of the 12-million kirana stores tracked by market researcher NielsenIQ, almost two-thirds or 8-9 million stores are in semi-urban and rural areas with the rest in urban markets.

Distributors are understandably upset; they believe the re-jigging of the margin structure should not have been done at this time as it may compel others to follow suit.

“This isn’t the time to push us into a corner. We need FMCG companies to support us, not disincentivise us with margin rejigs. We can’t do much if the market is sluggish,” says Dhairyashil Patil, president, All India Consumer Products Distributors Federation (AICPDF), an apex body of distributors in the country. AICPDF has written to HUL seeking clarity on the move and giving the company 10 days to reconsider its decision. In the event, there is no response from the firm, distributors say they may have to stop stocking HUL products to protest against the decision.

“A boycott will become inevitable if the company does not reconsider its decision. We have sought time with the company’s CEO & MD Rohit Jawa to understand the rationale behind the move. We view this as a serious matter,” he says.

But the company seems intent on going ahead with its plan, having unveiled the new margin structure across 100-150 towns last month following a pilot. It will be taken nationwide in phases over the next few months as it seeks to increase retail coverage. HUL reaches nine million outlets totally (directly and indirectly), the highest for an FMCG company in India. Some analysts see the cuts as a move to rationalise distribution costs. A mail sent to HUL remained unanswered till the time of going to press.

Navigating traditional trade

HUL’s decision to rejig its margin structure for general trade has significant repercussions for the domestic FMCG market. Cutting fixed margins will mean that the payout to general trade will be smaller. Variable pay, on the other hand, is performance-linked, hiking it hardly bodes well for traders struggling with weak sales, say experts. But this isn’t the first time that HUL has cut distributor margins. Until 2017, the company offered nearly 5% as a fixed margin to general trade (GT) in urban areas and 6% in rural areas. In that year the structure was altered with a 3.9% fixed margin for urban areas and 5% for rural areas. The latest round of cuts has revised these figures downwards further, say experts.

Out of place?

HUL has been pushing direct distribution aggressively over the last few years. It has tried to reach retail outlets directly through its Shikhar app, initiatives such as Smart Stores and by putting more feet on the ground. Sector analysts point out that the company has reduced its dependence on distributors. Nearly a third (or 3 million outlets) of HUL’s total retail reach of 9 million outlets is now serviced directly by the company.

Sachin Bobade, vice president, Dolat Capital, points out general trade has been facing liquidity constraints from consumers to retailers, notably, in rural areas. As a result, retailers are unable to pay distributors for the orders they place with them and this, in turn, has seen credit cycles go up significantly within trade. “Also, inventory is stuck because movement of goods is slow, since consumer offtake is low. All of this has possibly led some firms to question the efficacy of general trade,” Bobade told FE.

Varying strategies

But not all companies doubt the efficacy of general trade. Many such as Saugata Gupta, MD & CEO of Marico, the maker of Parachute and Saffola, have been vocal about revitalising general trade, describing the current challenges faced by the channel as short-term in nature.

“GT growth has to be rekindled because I think it’s important that it grows. If I look at a 20-30 years’ horizon, GT will continue to be important in India and it will be an ‘and’ growth and not an ‘or’ growth,” Gupta said on a recent investor call. Marico will launch some direct-to-consumer brands—True Elements in food and Plix in nutrition—via general trade as it attempts to reinvigorate the channel. Dabur, on the other hand, has increased its credit cycle to distributors to help them tide over the liquidity crisis they are facing. And Parle Products has reduced inventory clutter in retail stores, as it focuses on fewer stock-keeping units that move quickly off shelves.