By Raju Mansukhani

“The structure of political and military power on the Asian continent is changing profoundly. In recent times we have seen the almost certain reduction of British power for financial and other reasons in Southern Asia from Aden to Singapore,” wrote Walter Lippmann, an influential American journalist of his generation.

‘The Great Asian Disorders’ was the headline for his column on the editorial pages of National Herald, Lucknow edition, dated 21 September 1965. Taking a wide-angle view of Asian diplomacy, armed conflicts and crumbling centres of power, Lippmann wrote about, “the sharp and perhaps decisive alignment of Sukarno’s Indonesia with Red China. The disintegration of Malaysia and the virtual certainty that Singapore will cease to be a Western stronghold.”

He saw in the conflict between Pakistan and India immeasurable violence which “will leave the whole sub-continent sown with the seeds of revolution. The US position in Japan, in the Philippines, not to speak of Cambodia and Burma, is deteriorating.”

To give the US journalist his due, he was forthright in drawing attention to military and diplomatic machinations of Communist China. “Peking relishes the opportunity of fighting the United States by proxy…Peking does not want the Vietnamese war to end in the foreseeable future and that Peking will use all its influence to keep the war going and prevent a negotiated settlement.”

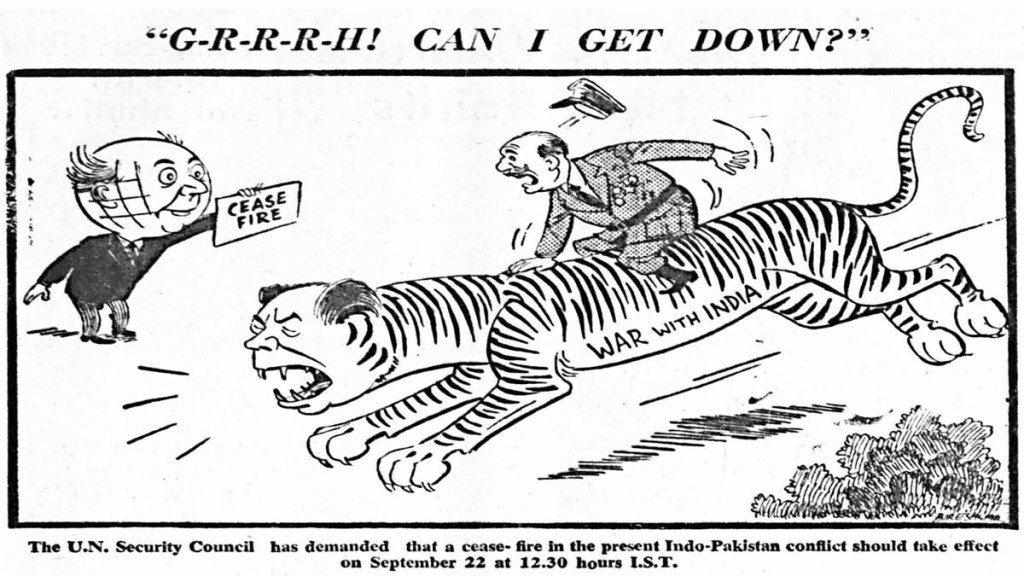

Infact the UN Security Council resolution, passed on 20 September 1965, took note of the role which China was playing in aggravating the Indo-Pakistani border war. While the Council demanded of both the Governments of India and Pakistan to effect a cease-fire in their conflict, with effect from 12.30 hours of 22 September, it also called upon “all states to refrain from any action which might aggravate the situation in the area.”

Clearly China’s geo-political games were being referred to and their war-games were no longer any State secret.

The UN resolution besides demanding a cease-fire also asked of both governments’ subsequent withdrawal of all armed personnel to positions held by them before August 5, 1965, and requested the Secretary-General to provide necessary assistance to ensure supervision of the cease-fire and withdrawal of all armed personnel.

The resolution, though disappointing aspects for India in certain respects, was a virtual diplomatic and political defeat for Pakistan.

The resolution recognised India’s positive response to the call for cease-fire and Pakistan’s negative response, in a preambular paragraph, by noting ‘differing replies’, reported the National Herald. The resolution was moved by Netherlands and was adopted with ten votes against nil. Jordan abstained from voting; while Malaysia expressed reservations on the political aspects of the resolution.

Also Read: 1965 Indo-Pak War: Scaling the peaks of diplomacy

Firing in Sikkim, Ladakh: Back in the Indian Parliament, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri said, “even before the expiry of the extended time limit, Chinese forces had started firing at Indian border posts both in Sikkim and in Ladakh. If China persists in aggression, we shall defend ourselves by all means at our disposal.”

“Our offer of resolving differences over these minor matters by peaceful means is still open. However, the Chinese aggressive intentions were clear from the fact that they started firing at Indian posts it is clear what China is looking for is not redress of grievances, real or imaginary, but some excuse to start its aggressive activities again, this time in collusion with its ally Pakistan, he said, adding, “What we should do and should not do about Kashmir is entirely our affair. Kashmir is an integral part of India.”

China was already encouraging insurgency in Nagaland. It was widely reported in the media, and discussed in Parliament that Chinese troops remained massed behind the passes through which they had poured into India in 1962.

On December 8 1964, the then Defence Minister YB Chavan told Parliament that fourteen to fifteen Chinese divisions were in position along the Sino-Indian border. “This equalled or perhaps exceeded the fears of the 1962 attacking force…the Indian Army obviously had to plan for the worst possible contingency. The potentialities included a two-front war against the land armies of Pakistan and Red China,” he stated.

In The Monsoon War, its authors Amarinder Singh and Lt. Gen Tajindar Shergill focus on the two crucial amendments to the Constitution of India on 4 December 1964 which were instrumental in upsetting Pakistani calculations.

The Indian Parliament extended two previously inapplicable articles of the Constitution of India to Jammu and Kashmir: these were Article 356 and Article 357. The Home Minister Gulzari Lal Nanda stated, “new legal steps would make empty and redundant the special status granted to Kashmir under the 1950 Constitution”.

Warning bells were now ringing in Pakistan; it had to take dramatic action, lest the entire issue disappear from international debate and world attention. The application of Articles 356 and 357 in Jammu and Kashmir became a specific factor for Pakistan to precipitate military hostilities. It had begun making preparation by early 1965. Bhutto, even in February 1964, was referring to Kashmir unrest as a ‘rebellion’.

Also Read: Revisiting the battlegrounds of Kargil: Prelude to the 1965 Indo-Pak War

War of Nerves: Russell Brines, the celebrated war correspondent of Associated Press whose book ‘The Indo-Pakistani Conflict’ was published in 1968, joined these dots in his narrative, looking back at 1963 and 1964.

“Throughout 1965, India and Pakistan waged a diplomatic and political war of nerves inflammable initiative produced sharp counter-action. Pakistan generally maintained the offensive, seeking to exert pressure on India by every means, propaganda campaign to persistent diplomatic attempts to isolate India internationally for this policy, Rawalpindi quite evidently placed great reliance upon the support of Red China,” he wrote.

Brines referred to the eight-day visit to Peking in March 1965 of President Ayub where he emphasized, in several speeches, the ‘friendship’ and ‘peaceful’ aspirations of the Chinese Communists. The Chinese Foreign Minister Marshal Chen Yi, without pledging military support to Pakistan, was reported by the Pakistani media, Dawn, stating, “China would go to the assistance of every friend, if asked for help against an aggressor.”

For Peking to defend Pakistan while she remained aligned with the United States would be a complete violation of Chinese doctrine, said Brines. But the AP war correspondent felt these factors would not prevent Communist China from intervening in a war on the sub-continent for its own advantage.

It was after the Chinese invasion of India in 1962 that its diplomatic and military ties with Pakistan were strengthened and formalized. Brines goes back to the Sino-Pakistan border agreement of 2 March 1963. Through this agreement, Pakistan conceded some 2000 sq miles of Hunza, lying in disputed Kashmir south of the Mintaka pass. Pakistan in turn got 750 sq miles of grazing land and salt mines which China had in actual fact abandoned in 1955.

The Monsoon War authors, Amarindar Singh and Lt. Gen. Tajindar Shergill said, “Peking had completely changed the strategic situation in the Himalayas and in Kashmir – by assault and by diplomacy. The Chinese military position after the agreement in Ladakh, the high passes and mountains in northern India, and Hunza, the valley in northern-most Pakistan, had negated all that the United Nations had striven for a period of fifteen years – to achieve a territorial agreement between India and Pakistan.”

The author is a researcher-writer specialising in history and heritage issues, and a former deputy curator of the Pradhanmantri Sangrahalaya.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal and do not reflect the official position or policy of Financial Express Online. Reproducing this content without permission is prohibited.