It’s funny how so many ‘concerns’ women are told they should care about didn’t just appear out of nowhere; they were sold to us. Taking a closer look will tell you how women’s clothes don’t have pockets, because where would handbags go then, the obsession with fair skin, the endless back and forth over sulphates in shampoo, the panic around “unruly” hair or ageing skin, even the idea that your body needs a special soap just because you’re a woman.

So, several such so-called standards weren’t born from need; they were born from marketing. And one of the first, most quietly powerful examples of this? Shaving. Specifically, the idea that women shouldn’t have body hair at all. Back in the early 1900s, no one really cared if women shaved. It wasn’t a hygiene factor. In fact, in many parts across the world, shaving was only common among courtesans to differentiate themselves from the royalty. But when fashion began to change, with sleeveless dresses and rising hemlines, a razor company saw something no one else did: a blank canvas not just of skin, but of possibility.

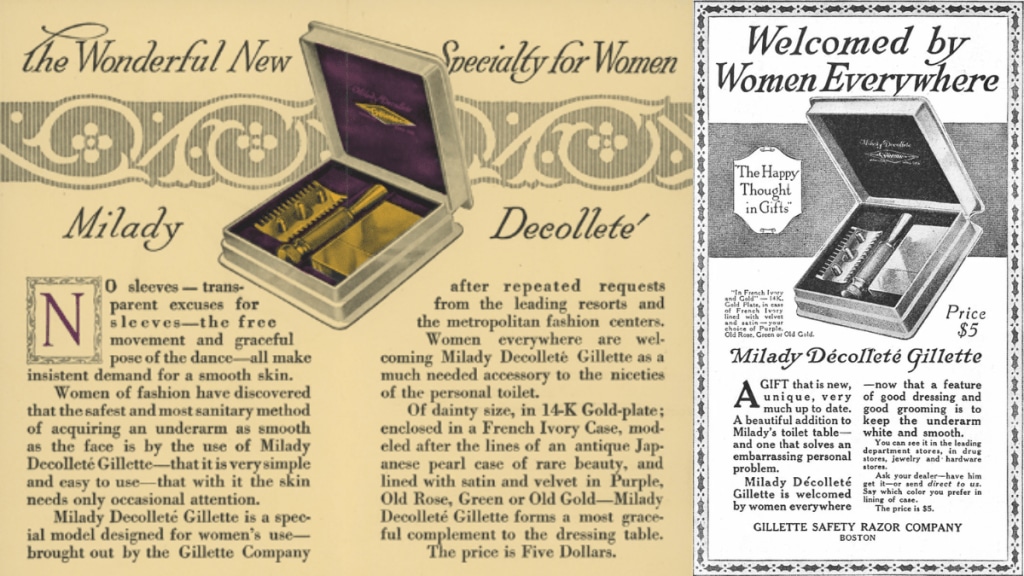

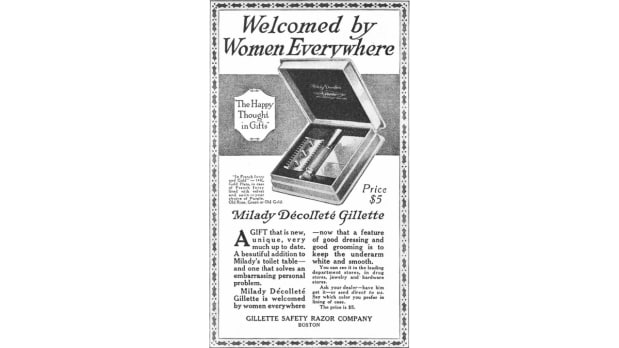

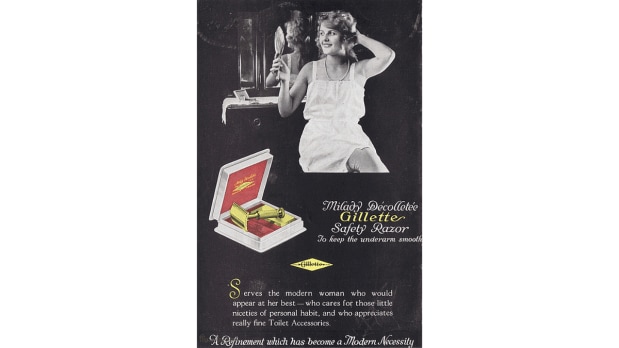

Enter “The First Great Anti-Hair Movement”, quite literally, that was the campaign Gillette started to introduce shaving to women, which has now become a societal expectation. In the summer of 1915, something unusual arrived on American store shelves: a sleek, gold-plated razor, designed not for men, but for women. It was called the Milady Decolletée, and its release would quietly ignite one of the most enduring and profitable norms of modern consumer culture. The product’s $5 price point (equivalent to approximately $150 today) intentionally positioned it as a premium offering, leveraging scarcity and exclusivity to generate aspirational demand.

Creating the need, then selling the solution

By marketing body hair as a “problem,” Gillette created a market from thin air. Advertisements framed smooth skin as essential to femininity, confidence, and even modernity. Being “well-groomed” suddenly meant being hairless, and by extension, a good razor became a beauty essential. Within two decades, millions of women who had never thought twice about leg or underarm hair were now making hair removal part of their weekly routines. The psychological shift was profound: body hair had become something to be hidden, managed, and ultimately erased. And so, a product that once had no natural market was now a household staple.

By the 1940s, shaving had become second nature for most American women. Not because razors had dramatically improved. Not because body hair posed a threat. But because enough women had been told that being hairless was beautiful, and enough others feared what it meant if they weren’t.

The business of beauty standards

This was not merely a case of effective advertising; it was a masterclass in category creation. By aligning personal grooming with ideals of sophistication, propriety, and femininity, the company transformed a private act into a social expectation. The commercial returns have been significant. The global women’s razor market size was valued at $ 3.97 billion in 2022 and is expected to reach $ 5.28 billion by 2028, with an expected CAGR of 4.85, even as the core technology, the blade, has seen minimal innovation. Razor products targeted at women routinely carry higher price tags than those marketed to men, a disparity now often labelled the “pink tax.” Despite criticism, the practice persists, buoyed by entrenched consumer behaviour and cultural norms.

The market, now, has evolved into multifolds with various techniques being incorporated, such as laser hair removal, sugaring, threading, waxing, epilation, etc. Major brands like Gillette (Venus), Veet, and Nair have long dominated store shelves, while smaller homegrown brands like The Bombay Shaving Company and Carmesi cater to modern consumers. Meanwhile, advancements in at-home laser devices by brands like Tria and Philips Lumea are making formerly salon-exclusive treatments more accessible.

Nevertheless, the foundational norms established by Gillette’s early campaigns remain largely intact. Shaving continues to be framed less as a personal choice and more as a cultural expectation.

And Gillette? Still cashing in. Because the real genius wasn’t the product. It was the story. A story that taught women to see something as wrong, and then offered them the right way to fix it.

A story that, over a hundred years later, still sells.