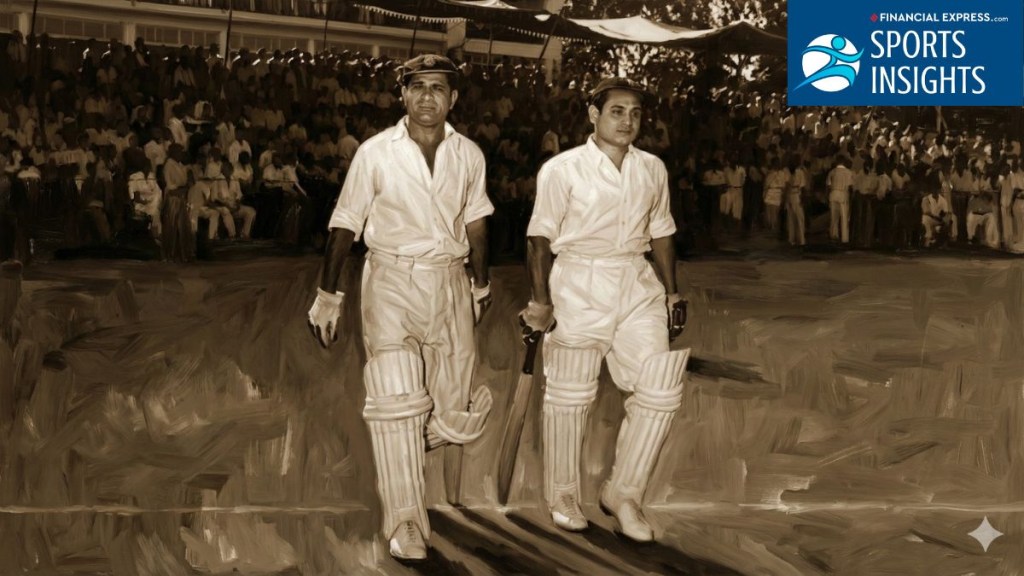

Seventy years back, two men spent two days batting. They made 413 runs before getting separated. That opening stand for India against New Zealand in Madras still stands today as the greatest by any Indian pair.

No one has topped it. Not even the mighty pairs of modern cricket with their flat tracks and power hitting. The record has outlived both batters. It has outlived the stadium where it was made. It has outlived the very idea that records are meant to be broken.

Unlikely pair who batted forever

You wouldn’t put Mankad and Roy in the same sentence as Hobbs and Sutcliffe. They were not Greenidge and Haynes. You don’t hear their names whispered together in cricketing folklore. They opened for India only nine times in their whole careers.

Yet on January 6 and 7, 1956, they became the third pair in Test history to bat an entire day without getting out. The New Zealand bowlers kept coming and the two kept batting. The ball got old. The bowlers got tired. The fielders started dreaming of dinner. Still they batted.

This was the last Test of a five-test series between India and New Zealand. India already had one win in their pocket. Three other games ended in draws. New Zealand attack was friendly. The pitch was a road. Indian batsmen had been piling up runs all series.

Polly Umrigar and Mankad had already made double hundreds. Five other batters had hit centuries. So when Umrigar won the toss on another flat track, everyone expected more runs. But 413 for the first wicket? That was madness.

The man who found his vision

Pankaj Roy was short-sighted. He found this out just weeks before the series began. Minus one power. A friend who was an optometrist convinced him to try glasses. Roy refused at first. He was opening the batting, for god’s sake.

A fast bowler hits you in the face and the glass shatters in your eyes. Game over. Life over. Doctor asked him a simple question: how many times have you been hit in the face? Roy said never. So the doctor said, then why worry?

Roy wore the glasses in the first Test at Hyderabad. Everyone was shocked. Roy the opener had put on glasses. He scored zero. The selectors dropped the pair for the next three Tests. They tried Vijay Mehra. They tried Nari Contractor. Nothing worked.

For the final Test in Madras, they went back to Mankad and Roy. The glasses stayed on. Roy would later tell Mihir Bose that the glasses were a revelation. He could see the ball properly for the first time. That minor correction changed everything.

A day that never ended

Day one started. Hayes and MacGibbon had the new ball. They were accurate but not frightening. Mankad and Roy took their time. They scored in singles and twos. Occasionally a four. Roy reached his hundred first in 262 minutes. Mankad got there just before stumps.

When they finally walked off, the board showed 234. Zero wickets down. Roy had 114. Mankad had 109. Remember that 203-run opening stand by Merchant and Mushtaq Ali in Manchester? They had crossed that. They were the first Indian pair to bat through a full day’s play.

The dressing room must have been quiet that evening. What do you say to two men who have batted all day? Well batted?

Lunch that changed everything

Day two began the same way. More batting. More runs. The 300 partnership came. Then Mankad’s 150. Then Roy’s 150. The real target was 359. That was the world record. Len Hutton and Cyril Washbrook had made that against South Africa in Johannesburg in 1948-49.

Mankad and Roy passed it shortly after lunch. Madras crowd woke up. The record was happening in front of them. Then came the 400. Then Mankad’s double hundred. This was his second of the series. Only Don Bradman and Wally Hammond had done that before him.

The word came from the pavilion around this time. The captain wanted a declaration. Roy tried to force the pace. Poore bowled him for 173. The partnership ended at 413. They had batted 472 minutes. Eight hours. Facing six bowlers.

Mankad went on to 231. That became the highest score by an Indian in Tests. It stayed that way until Sunil Gavaskar made 236 not out in Chennai in 1983-84. India declared at 537 for 3. Their highest Test total ever. They won by an innings and 109 runs.

Chase that never succeeded

The record stood. Bobby Simpson and Bill Lawry made 382 for Australia against West Indies in 1965. Seven years later, Glenn Turner and Terry Jarvis made 387 for New Zealand against West Indies. Close but not close enough.

Then January 2006 arrived. Sehwag and Dravid were batting in Lahore against Pakistan. They raced past 300. Then 350. Then 400. The Madras record was right there. Just three runs away at 410. Then Sehwag got out.

Two years later, Graeme Smith and Neil McKenzie finally broke the world record. They made 415 for South Africa against Bangladesh in Chittagong. But the Indian record? Untouched.

Numbers that don’t make sense

Think about this. Over 500 Test matches have been played by India since that Madras morning. Their best opening pairs in history have tried. Gavaskar and Chauhan. Sehwag and Gambhir. Jaiswal and Rohit. No one has come close except Sehwag-Dravid, and that wasn’t even a regular opening pair.

The pitch was easy, yes. The bowling was ordinary, yes. But 413 runs? You have to concentrate for two days. You have to want to bat that long. Most modern batters don’t know how to do that. They don’t need to. They have T20 leagues and strike rates to worry about.

Roy died in 2001. Mankad had already gone in 1978. But those who watched probably remembered that day. The runs that changed nothing but meant everything.

Record that lives on

Today, the Corporation Stadium is called Nehru Stadium. It doesn’t host Test matches anymore. The world has moved to Chepauk, just a few kilometers away. But in the record books, that 413-run stand lives. It is Indian cricket’s most stubborn number. It refuses to change.

Sachin’s 51 Test centuries is a world record. Kapil Dev‘s 434 Test wickets was also a world record. But those are individual feats. This was a partnership. Two men who understood each other for 472 minutes and then went their separate ways.

They opened together only nine times. They scored 413 runs in one of those times. Seventy years later, that number looks back at us. It asks a simple question: can anyone bat that long again? The answer is still no.