A charge to use the Unified Platform Interface (UPI) has been a contentious issue for quite some time. Last week, National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) managing director Dilip Asbe set the cat among the pigeons when he said large merchants may need to fork out a ‘reasonable’ charge for UPI-based payments sometime in the next three years.

It is a sensible thing to do, though sceptics will be quick to point out that the merchants will pass on the cost to the consumer. That may or may not happen, depending on the merchant’s need to retain the customer. Many consumers these days are getting hooked to the ease of digital payments and are, therefore, willing to pay a little extra for the faster delivery of goods. Given that it has been an unqualified success, with transactions having touched a value of Rs 183 trillion in 2023 and volumes having topped 117.5 billion, it should not be difficult to get stakeholders across the transaction chain to pay.

This includes consumers who are becoming too used to getting the service not just free but who also expect apps to reward them via cash-backs and discounts. As Axis Bank chief Amitabh Chaudhry had observed in no uncertain terms, banks do not have the money to burn to build payments businesses. Chaudhry was more than justified in his assertion that the bank didn’t have Rs 3,000 crore to fritter away. Indeed, banks have every right to focus on businesses they believe are profitable and in their interest. The Reserve Bank of India, which had reportedly chided the lender for not making much headway in the UPI space, has absolutely no business to interfere in banks’ choice of investment areas, especially when these are loss-making.

The fact is that payments services are not a paying proposition. Banks are answerable to their public shareholders, and it simply doesn’t make sense for them to spend large amounts on cashbacks and other freebies, to acquire customers. There is no doubt that serious amount of investments will be required to convince people, who are on the edge, that digital payments are safe, provide incentives and cashbacks. On the other hands, should fintechs funded by private equity players want to pursue this line of business and accommodate losses, it is entirely their decision. Many banks believe they can cross-sell other products to customers who start off by using the payments services.

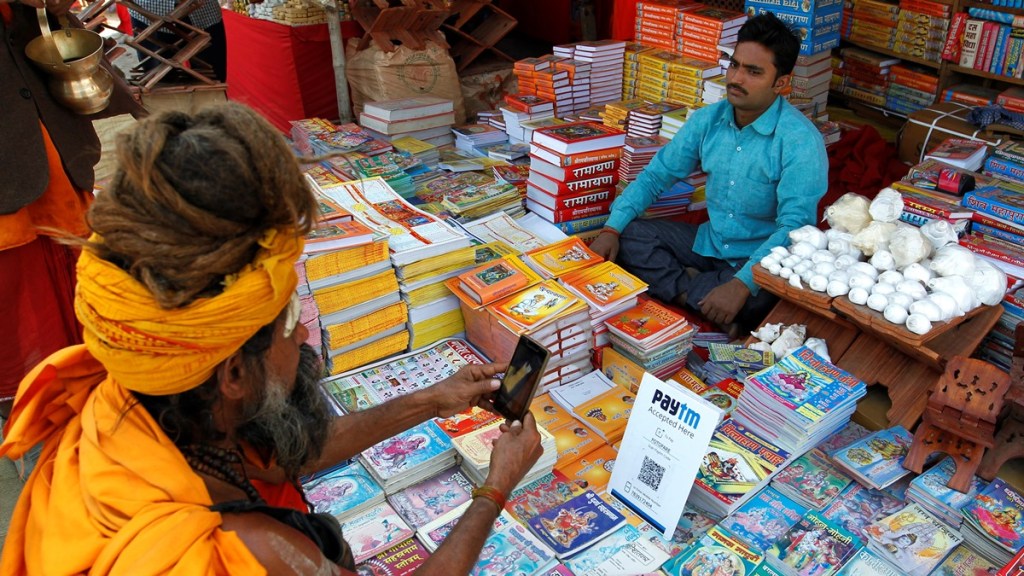

In March last year, NPCI had introduced an inter-change fee on merchant transactions, based on pre-paid instruments, with a value of over Rs 2,000. The interchange rates vary between 0.5-1.1% depending on the profile of the merchant. Much like this, one assumes that the charge to be paid by merchants will first be rolled out for high-value transactions. While implementing the pricing structure, smaller merchants should be protected.

In December 2017, the RBI had lowered the merchant discount rates (MDR) on debit cards while capping the charges based on the size of the merchant instead of the transaction value, as was the earlier practice. While banks did sulk since their revenues would have been hit, the bigger volumes of digital payments must have compensated for the cut. Similarly, merchants too are likely to gain from bigger volumes even if there is some initial pain. A micro-charge on certain transactions may make UPI much more viable and keep it going—without losing its popularity.