By Ranveer Nagaich & Janak Priyani

Last month, the Monetary Policy Committee of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) reduced the policy rate by 25 basis points, against the backdrop of a slowdown in global as well as domestic growth. In its monetary policy statement, the central bank mentions that the recent slowdown in the March 2019 quarter is predominantly a consequence of decelerating consumption and export growth in the previous quarter. So, the question needs to be asked: What has been affecting consumer demand?

To understand consumer behaviour better, we have to go back to the basic microeconomic theory. First, we need to understand the difference between the change in quantity demanded versus change in demand. A change in prices leads to adjustments in quantity demanded, not demand. Therefore, in a relatively benign inflation environment, there should be a positive change in quantity demanded, leading to a temporary increase in prices. This, in turn, prompts an increase in quantity supplied, taking us back to our equilibrium price. In essence, this is a movement along the demand/supply curves, rather than shifts.

The factors affecting demand are, however, not necessarily price-sensitive. Income, preferences and confidence in the economy affect demand—resulting in a shift of the demand curve. These factors reflect the consumers’ ability and willingness to pay. An increase in incomes, for example, would raise demand at every price point, not just one. The reverse holds true as well—a decrease in incomes will reduce demand at every price point. The ongoing debate about rural distress in India is essentially about the income effect.

As incomes affect the ability to pay, preferences affect the willingness to pay. For example, even though consumption as a proportion of GDP has stayed at nearly 59% over the past 15 years, the composition has undergone a shift. While food and beverages have seen the most decline as a percentage of GDP, expenditure on recreation, education and cultural services has actually grown the most.

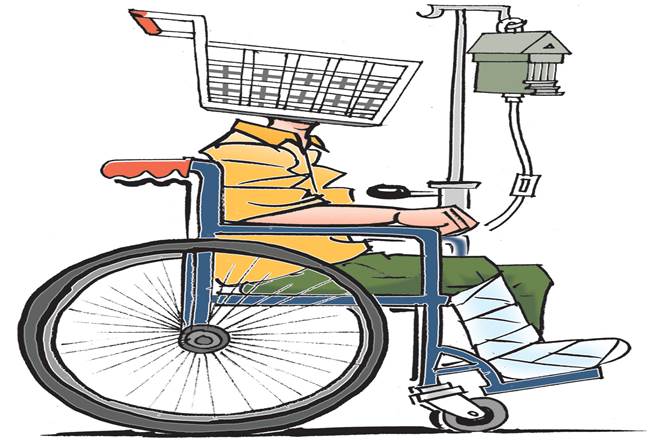

However, in an economy where the current consumption can be financed through credit, willingness and ability to pay also depend heavily on credit availability. Consider automobile sales. A large chunk of these sales are financed through various non-banking financial companies (NBFCs). Retail lending from NBFCs saw a decline of 13% year-on-year in the December 2018 quarter from the growth in lending of 21% year-on-year in the previous quarter. Could this be a possible explanation for the deceleration in the sales of consumer durables?

An argument can be made that there is a large unfulfilled demand in India’s credit markets that is holding back consumer demand. For example, vehicle loans extended by commercial banks have been showing signs of deceleration as well. Between calendar years 2015 and 2017, vehicle loans grew at an average rate of 15.8% year-on-year. In 2018, growth in loans decelerated to 9.6% year-on-year, and in 2019 further decelerated to 6.1% (till May 2019). Clearly, access to credit is impeding consumption activity in the economy. The case of consumer durables’ loans is even more tricky. According to RBI data, outstanding consumer durable loans as of July 2018 stood at Rs 20,469 crore. And outstanding consumer durable loans as of May 2019 stood at a meagre Rs 6,063 crore, a precipitous fall.

There is evidence that displays a slowdown in consumption growth. Automobile sales are in a slump, and most FMCG companies reported a slowdown in earnings growth in the March quarter. This decline is further reflected in the Index of Industrial Production (IIP) numbers, which show deceleration in both consumer durables’ and non-durables’ output.

However, there are signs of green shoots. For instance, in the March 2019 quarter, we have seen NBFC retail lending rise by 18.6% year-on-year, compared to a decline of 13% year-on-year in December 2018. Similarly, housing loans continue to grow at a healthy pace, clocking growth of 18.7% year-on-year in May 2019. Accordingly, many analysts see this slowdown as temporary, and expect consumption to drive India’s growth story in the future. However, steps must be taken now so as to ensure a smooth growth trajectory for consumption demand, reducing volatility and uncertainty.

With inflation close to the lower bound, an argument can be made for further rate reductions to bring down the real cost of borrowing. A strong policy response to reduce the cost of credit and increase the access to credit for consumers will lead to increased confidence in the economy. As RBI mentions in its statement, it is the sentiment which is weak, but very ironically, it doesn’t recognise the major factor affecting it. After the cumulative 50-basis-point cut in the policy rate, there was a 21-basis-point cut in fresh loan rates. In an environment of imperfect monetary transmission, successive rate cuts may be needed to bring down the cost of lending.

Apart from reducing the cost of credit, expanding the availability of credit is of equal, if not greater importance. Consider the following: Domestic credit to the private sector (as a percentage of GDP) in India stands at 49.9% of GDP, whilst that of China stands at 161%. In upper-middle income countries, this number stands at 120.7%. This indicates there is substantial room to expand credit access in India.

Leveraging technology through fintech firms to expand access to credit provides a crucial avenue. RBI has been working on a regulatory sandbox for fintech firms since the beginning of the fiscal. Efforts should be made to operationalise this sandbox as soon as possible, as India can make significant inroads in this nascent industry. The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) has estimated that the digital lending business in India can exceed $1 trillion by 2023, confirming the enormous potential offered by this sector. Retail lending can get a much-needed fillip, boosting consumption (especially that of durables), whilst the bank clean-up process is on.

While the theory of ‘loanable funds’ has been subject to intense debate over the past century, it provides an interesting framework to view India’s current situation. In this framework, it is our contention that the pool of loanable funds needs to be expanded. The demand for credit is in excess of supply, pushing up the real cost of capital. A holistic approach to credit markets, balancing the credit needs of households, MSMEs, private corporations and, of course, the government is needed, ensuring that public investment ‘crowds in’ private investment and consumption, not ‘crowds out’.

(Authors are Young Professionals, NITI Aayog. Views are personal)