As we await the recommendations of the Bimal Jalan chaired committee on RBI Economic Capital Framework, this article tries to present a simplified description of the balance sheet of the central bank, a very arcane and complex topic by nature. Assessing the space open to RBI to transfer a portion of its capital to the union fisc is only a very secondary objective.

RBI’s operations are organised into the Banking and Issue Departments, the latter being in charge of currency issuance (RBI’s financial year is on a July-June basis). A central bank has two primary sources of income: (i) “seigniorage”, arising from the ability to print money (at zero or nominal printing cost) and deriving incomes from deploying these monies in assets; and (ii) a tax on banks, through requiring reserves at costs usually lower than system cost of funds (in RBI’s case, CRR is unremunerated). Secondary incomes are derived from the primary sources via returns on investments.

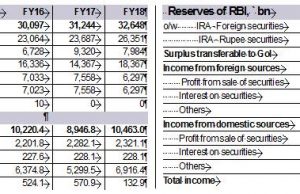

As of June 30, 2018, RBI’s capital plus reserves (including payment of dividend to the government) was Rs 10.46 lakh crores (` trillion), or about 28% of total assets. Of this, the Contingency Fund (CF) is Rs2.32 trillion (6.4% of assets), representing a rainy day fund of specific provision made by RBI, “meant for meeting unexpected and unforeseen contingencies, including depreciation in the value of securities, risks arising out of monetary/exchange rate policy operations, systemic risks and any risk arising on account of the special responsibilities of RBI.”

The remainder mainly consists of revaluation accounts, as RBI’s foreign and domestic assets are marked to market (MTM) and fluctuate in value with interest and exchange rates. Within this, the Investment Revaluation Account (IRA) on INR securities is Rs 0.13 trillion. The Currency and Gold Revaluation Account (CGRA) is Rs 6.92 trillion (19.1% of total assets), accounting for MTM on foreign currency and gold assets. CGRA is created so the balance sheet matches when foreign exchange reserves are restated in INR. Essentially, these represent valuation of reserves held from point of purchase. Under the RBI’s accounting policy, revaluation gains on currency and bonds is not considered as capital, and is only seen as an accounting entry (consistent with BIS norms).

So, how much of these reserves can potentially be transferred? CGRA is converted into income and profits when reserves are sold, e.g., if $1 billion was bought at 45 rupees to the dollar, and sold at 65, the Rs 20 billion change in valuation would be booked as profit into the P&L (transferred from CGRA) on the date of sale.

An estimate of how much of the CGRA can be freed can be derived as follows. RBI could have bought domestic assets rather than foreign assets, either through repos or OMOs. These domestic assets would have earned interest income in excess of the much lower rates of foreign assets, probably around 3-4% higher. Going by uncovered interest parity, the depreciation of INR against developed market (DM) currencies is at least partly in lieu of interest income lost, and is probably irreversible. This implies that 3-4% of reserves could have been added to seigniorage income, instead of simply to revaluation reserves, with the gradual drawdown of revaluation reserves likely be replenished as INR continues to depreciate. At 3% seigniorage passed on every year, Rs 4.1 trillion might have been cumulatively passed on as income since FY09 rather than retained in CGRA, when DM interest rates fell. A milder 2% seigniorage would have resulted in Rs 2.72 trillion passed on over the same period. However, this depreciation might be lower going forward, given sustained Indian inflation at 4% now while inflation in DMs (RBI holds a basket of DM currencies) is likely to converge to 2% in the medium term. The transfer possible on an ongoing basis may therefore be rather small.

The extent of drawdown of the reserves needs to be consistent with the risks that RBI balance sheet is supposed to absorb. RBI is estimated to hold Rs11 trillion of GSecs, with 3.8 year duration. Average standard deviation of 10 year Gsec yield change is 80 bps on an annualised basis, hence 3 sigma would be 240 bps. Thus, expected extreme loss would be Rs 1 trillion. Recall that the Investment Revaluation Account was only `133 billion at end-June 2018 (although is likely to have increased in FY19). Hence, if this risk were to be realised, the IRA could be wiped out and significantly eat into the Contingency Fund (Rs 2.3 trillion). This could potentially impair RBI from performing its other functions credibly. Hence, possibility of transfers from the Contingency Fund appear very limited.

Much easier to justify are transfers from the CGRA, as discussed above. But this does not take into account the risks arising from India’s external accounts. As the accompanying graphic shows, the largest share of RBI assets is invested in foreign securities (`26.4 trillion of Rs36.2 trillion) and the majority of this is reported against the Issue Department (`18.4 trillion). This is meant to back RBI’s monetary liabilities as a measure of trust in the Indian currency (India’s monetary base, M0, was Rs 24.9 trillion at end-June 2018). At end-June 2018, Issue Dept investment was 74% of the M0 base (vs 70% in June 2017). The forex assets of the Banking Dept were $117 billion (end June 2018 at then USD/INR), i.e., 119% of the then short-term external debt of $99 billion. This was significantly lower than the 163% at end-June 2017.

So, might a transfer actually be operationalised? Any transfer would entail a corresponding sale of assets from RBI holdings, given that profits first need to be realised. Sale of both foreign and domestic securities, unfortunately, will tend to (a) push prices of USD/INR or GoI securities down, tightening conditions at a time when the intent and stance of monetary policy is accommodation and (b) extract domestic liquidity, thereby pushing the spreads of market instruments over the equivalent sovereign bonds, further limiting monetary policy stimulus.

It is uncertain whether RBI’s policies allow it to automatically monetise valuation gains and pass them on to shareholders. However, this might not be required. RBI can enter into sell/buy swaps, or sell and buy back reserves on the same day. This would book valuation profits at once, and the liquidity absorbed from the system would be the amount of profit booked, rather than the entire asset value.

With contributions from Tanay Dalal